Abandoned SS Ayrfield – Australia’s Floating Forest Shipwreck at Wentworth Point

The SS Ayrfield rests quietly at Wentworth Point in New South Wales, offering a haunting yet beautiful reminder of Australia’s maritime history. Once a proud steel-hulled vessel, it now stands as a striking ruin, its rusting frame surrounded by lush mangrove growth that has taken over its structure. This natural reclamation has transformed the SS Ayrfield into a surreal blend of human industry and wild nature, making it one of the most iconic shipwrecks in the region.

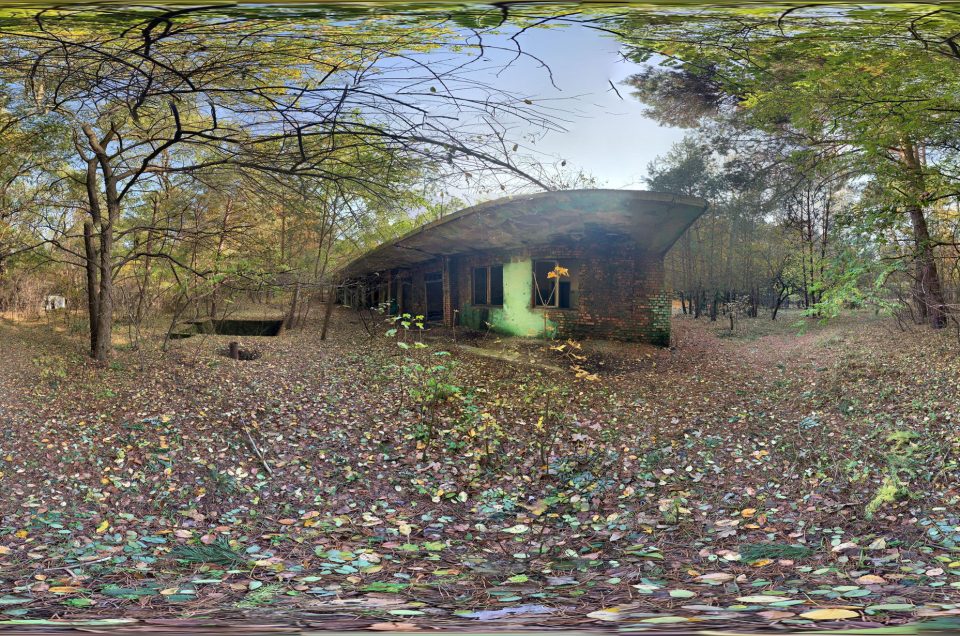

For urban explorers, the SS Ayrfield is more than just an abandoned relic—it’s a living monument to time, decay, and resilience. Through the stunning aerial 360-degree panoramic image available on Google Maps Street View, you can appreciate the full scope of its presence in the bay. The view captures not only the skeletal remains of the ship but also the unique atmosphere of its surroundings, allowing adventurers and history enthusiasts alike to experience the site’s mystery and allure from every angle.

Photo by: Grae McDowell

The rusted hull of the ship rises from the tranquil waters, draped in vibrant green mangrove trees – a striking sight that seems almost too surreal to be real. This is the SS Ayrfield, the famous “Floating Forest” of Wentworth Point in New South Wales, Australia. Once a sturdy steamship plying the seas, the SS Ayrfield today stands as an abandoned relic of the past, embraced by nature and transformed into a unique ecosystem. For enthusiasts of urban exploring in Australia, this century-old shipwreck is a must-see marvel, blending history, decay, and rebirth in one captivating location. In this blog post, we’ll dive deep into the story of the SS Ayrfield – including the year it was built, its decades of operation and activities, how it came to be abandoned, and the historical significance that makes it such an alluring destination for urban explorers.

History of the SS Ayrfield: From Workhorse to War Service

Every great ruin has an origin story. The tale of SS Ayrfield begins in the early 20th century at a British shipyard. SS Ayrfield was originally launched under the name SS Corrimal and built in 1911 in the United Kingdom. This steel-hulled, single-screw steam collier (coal transport ship) weighed about 1,140 tonnes and measured roughly 79 meters (260 feet) long. By 1912, the freshly built vessel was registered in Sydney, Australia, ready to serve the bustling maritime trade of the time. In an era when ships were the lifeline of commerce and industry, the Corrimal joined the fleet of hardworking freighters carrying resources and goods across the waves.

During its early years, the ship primarily hauled coal. The name “Corrimal” itself hints at this role – likely derived from Corrimal, a coal-mining town in New South Wales. As a steam collier, the vessel’s job was to ferry coal between ports, a crucial task in fueling factories, power stations, and steamships in the early 1900s. Based out of Sydney, it often ran routes shuttling coal from the Newcastle coal fields down to ports like Sydney Harbour. These routine coal runs earned the ship little fame, but they built a foundation of reliable service.

However, the outbreak of World War II would catapult the humble collier into a more pivotal mission. The Commonwealth Government requisitioned the vessel during the war, and under government service the ship was renamed SS Ayrfield (after one of Sydney’s northern suburbs). During the Second World War, SS Ayrfield was used to transport vital supplies, including food and armaments, to Allied forces – particularly the U.S. troops stationed in the Pacific theater. In this capacity, the ship braved long voyages through potentially hostile waters, delivering much-needed cargo to support the war effort. Its solid construction and dependable performance proved valuable amid wartime demands. The SS Ayrfield survived the perils of World War II, playing a small but steady role in the massive Allied supply chain across the Pacific.

When the guns fell silent and the war ended in 1945, SS Ayrfield returned to civilian duties. In the post-war years, the ship found itself back in the less-glamorous but essential work of hauling commodities. Records indicate that around 1950 the vessel was sold to an Australian oil company for a short period. Not long after, ownership passed to the Miller Steamship Company in 1951, which officially christened it SS Ayrfield, the name it retains to this day. Under Miller Steamship’s banner, the aging freighter spent the 1950s and 1960s primarily as a coal carrier once again – often running coal between the port of Newcastle and Miller’s terminal in Sydney’s Blackwattle Bay. Day in and day out, the hardy ship plodded along the Australian coast, linking coal mines with the industries that depended on them.

By the early 1970s, the SS Ayrfield had clocked in roughly six decades of continuous service. That longevity is a testament to the ship’s sturdy build and the care of its operators. But time catches up with every vessel. In 1972, at 61 years old, the SS Ayrfield was finally retired from active duty. The decision was likely due to the ship’s age and the availability of more modern vessels; maintaining an old steamer was no longer economical. Thus ended the working life of a ship that had seen the transition from coal-fired steam power to the jet age, and from world war to post-war prosperity. However, an even more fascinating chapter of its story was about to begin – one that would ensure the SS Ayrfield’s name lived on far beyond its seafaring years.

The Final Voyage: How the SS Ayrfield Was Abandoned

Upon retirement, ships like the SS Ayrfield typically meet one of a few fates: scrapping, sinking, or being preserved as a museum. For the SS Ayrfield, the intended fate was scrapping. In 1972, the vessel steamed into Homebush Bay, on the Parramatta River west of Sydney, which at the time served as a ship-breaking yard. Homebush Bay in the mid-20th century was an industrial backwater – a place where unwanted ships were sent to be dismantled for scrap metal and parts. The bay’s remote location and existing heavy industries made it an ideal graveyard for decommissioned vessels.

The SS Ayrfield arrived here along with several other obsolete ships, destined for the cutters’ torches. Indeed, multiple ship hulks were brought to Homebush Bay in the 1970s, including the colliers SS Mortlake Bank, the tugboat SS Heroic, and the boom-defense vessel HMAS Karangi, all of which were broken up around the same time. The scene must have been a grim one for a proud old ship – beached or at anchor in shallow bay waters, awaiting dismemberment after years of faithful service.

Yet, in a twist of fate, SS Ayrfield’s destruction was never completed. The ship-breaking operations in Homebush Bay ceased before the Ayrfield could be fully dismantled. The reasons for this abandonment were a mix of economic and environmental factors. In the early 1970s, shifts in the global steel market likely made the scrap metal from these ships less valuable, reducing the incentive to finish breaking them up. It’s said that the cost of fully dismantling the Ayrfield may have exceeded any profit from selling its scrap steel. At the same time, Sydney was turning its attention toward urban development and preparing to clean up its industrial wastelands, which meant the old ship-breaking yard was winding down. Simply put, the workers downed their tools and left, and the SS Ayrfield – along with a handful of other ship hulks – was left to rust quietly in the bay.

What exactly did “abandonment” look like for the SS Ayrfield? Essentially, the ship was stripped of usable materials and then left to sit in the water. Its once-busy engine fell silent, and its steel superstructure began to decay. In fact, much of the upper structure was likely removed during the partial scrapping process, leaving only the hollow steel hull behind. If you visit today, you’ll notice there’s no bridge, no masts, and no deckhouses – just the skeleton hull. After the ship-breakers halted work, nature and time became the new owners of the SS Ayrfield. The vessel remained afloat but moored in the shallow, brackish waters near the southwestern shore of Homebush Bay, not far from the current suburb of Wentworth Point.

Thus, a ship that had traversed oceans was now trapped in limbo, neither fully alive nor completely destroyed. It sat in the same spot year after year, weathering decades of sun, wind, and rain. In those early years of abandonment, the SS Ayrfield was probably just one of many unsightly rusting hulks polluting the bay. Homebush Bay itself was heavily contaminated from past industries – a dumping ground for chemical waste and other debris. The waters around the wreck were laced with everything from dioxins to heavy metals, remnants of a less environmentally-conscious era. Few could have imagined that this forlorn ship would one day transform into something beautiful.

Nature’s Takeover: The Floating Forest Emerges

Left to the elements, SS Ayrfield’s story did not end with corrosion and collapse – it took a dramatic turn towards rebirth. Over the decades following its abandonment, an incredible natural colonization occurred. Mangrove trees – hardy, salt-tolerant plants common to Sydney’s wetlands – began to take root in the silt and detritus accumulated within the Ayrfield’s hull. Perhaps it started with a few wind-blown seeds lodging in the muck on the deck or between rusting rivets. With no human crew to swab the decks or maintain the ship, the seeds found purchase and sprouted. The young mangroves extended their roots into the moist, brackish sediment that had collected in the hull’s bottom. Year by year, those roots spread and thickened, anchoring the trees firmly inside the steel shell of the ship.

Sydney’s climate and the nutrient-rich environment of the bay allowed the mangroves to thrive. The once-dark hold of the collier filled with life and green foliage. As the mangrove trees grew taller, they burst out above the ship’s sides. By the turn of the 21st century, the SS Ayrfield had been dramatically transformed into a Floating Forest, with dense clusters of mangrove vegetation spilling over its rusted hull. The sight is at once eerie and enchanting – gnarled roots and branches entwined with rusted iron, leaves rustling where sailors once trod the decks, and seabirds now perching where coal was once heaped.

This astonishing fusion of nature and machine captured the public’s imagination. The SS Ayrfield went from an obscure piece of junk to a celebrated curiosity. As urban development sprang up around Homebush Bay (spurred by the area’s rehabilitation for the 2000 Sydney Olympics) the Floating Forest suddenly had eyes upon it. Apartment buildings rose in Wentworth Point and Rhodes across the water, and waterfront parks and walkways were created – all offering views of the bay’s mysterious green-topped shipwreck. The ship that had once delivered supplies for war now delivered a visual metaphor: nature reclaiming the works of man.

Scientists and environmentalists have noted how the SS Ayrfield has effectively become a mini-ecosystem of its own. The mangroves embedded in the hull provide habitat and shelter for various creatures. It’s common to see fish schooling in the shade of the wreck, crustaceans clinging to its submerged portions, and birds flitting in and out of the tree branches. In this way, the hulk has become an artificial island, supporting life in the bay. The “floating forest” may not actually float (the ship is resting on the bay’s shallow floor), but it does ride the tides and remains waterborne. It’s a living example of how quickly nature can soften and even beautify the edges of industrial ruin.

From a cultural standpoint, SS Ayrfield’s rebirth as the Floating Forest has made it an icon of Sydney. Images of this mangrove-cloaked shipwreck have been shared widely, inspiring photographers, tourists, and locals alike. There’s something profoundly poetic about the scene – it’s often cited as a symbol of renewal and the transient nature of human creations. The ship survived war and decades of hard work, but it could not withstand the gentle, persistent advance of nature. As one writer put it, “Floating Forest” is a perfect case of preservation by neglect. By doing nothing at all, humans allowed the ship to evolve into a unique historical monument, one that is arguably more compelling than any static museum display.

To this day, no formal conservation efforts have been made on SS Ayrfield – its appeal lies in its natural state of ruin and regrowth. Authorities have opted to let it be, viewing it as both a historic wreck and an ecological feature. In an era when many abandoned sites are demolished for safety or aesthetics, the Floating Forest stands out as a happy exception where decay itself became the attraction.

Visiting the SS Ayrfield: Urban Exploration at Wentworth Point

For urban explorers and photographers, the SS Ayrfield is a dream location – albeit one that requires no climbing through broken windows or sneaking past “No Trespassing” signs. This abandoned ship is accessible to anyone in the sense that it can be freely viewed from public land; however, reaching out and touching it is another matter. The wreck lies in the waters of Homebush Bay, roughly 30 meters offshore from the walking path at Wentworth Point, a suburb on the bay’s western shore. The exact spot is near the end of Burroway Road, at a place aptly nicknamed the “Shipwreck Lookout.” From this vantage, you can get an excellent view of the Floating Forest across a narrow channel.

If you’re planning a visit, here are some tips to make the most of this urban exploring in Australia experience. First, timing is everything. The golden hours of sunrise and sunset are magical at SS Ayrfield. In early morning, mist may cling to the water as the first light illuminates the green mangroves against the rusty hull. At sunset, the ship becomes a silhouette of dark red and orange, crowned by vibrant greenery against the sky – a truly photogenic scene that has graced many an Instagram feed. Bring a camera; a zoom lens can help capture details of the mangrove trees and the texture of the rusting metal, while a wide-angle shot can frame the entire ship against the bay and sky.

While the SS Ayrfield is an abandoned site, it’s important to note that it is not an invitation for climbing or physical exploration on the structure. In fact, direct access to the wreck is prohibited for safety and environmental reasons. The hull is over a century old and corroded; any attempt to board the ship could be extremely dangerous, risking collapse or injury. Additionally, the wreck has become a protected habitat of sorts – trudging through it would disturb the mangroves and wildlife. For these reasons, urban explorers must admire this one from a respectful distance. Fortunately, the view from land is more than sufficient to appreciate its beauty, and it also underlines a key principle of urban exploration: sometimes it’s about observation and appreciation, not intrusion.

For those keen to get a slightly closer look, kayaking or paddleboarding in Homebush Bay is an option. On a calm day, paddling out on the water can offer a 360-degree perspective of SS Ayrfield and even a peek inside its forested interior from angles you can’t see on land. Adventurous kayakers often glide carefully around the wreck’s perimeter (staying a safe distance to avoid damaging the site or themselves). It’s an eerie feeling to float next to the ship’s towering rusted walls with birds chirping in the trees above you. If you do go by water, exercise caution – the bay’s maritime exclusion zones (especially during any nearby construction or events) should be respected, and the structure itself can be unstable. Remember, the goal is to enjoy, not to interfere with this piece of living history.

Wentworth Point and the surrounding Sydney Olympic Park area also have other attractions that complement a visit to the Floating Forest. There are walking and cycling trails through mangrove stands (the Badu Mangroves boardwalk is nearby) and information signs about the bay’s history. In effect, the whole area is a blend of nature, recreation, and remnants of the past. After marveling at SS Ayrfield, an explorer can also spot the rusted remains of the Mortlake Bank and HMAS Karangi not far away, especially at low tide. These hulks are lower in profile and less overgrown, so they’re not as immediately striking as the Ayrfield, but they add context – this truly was a graveyard of ships, and Ayrfield is simply the most famous tombstone.

One aspect that makes visiting SS Ayrfield rewarding is that it’s a legal and accessible adventure. Many abandoned places in Australia are off-limits or hidden on private property, making urban exploration a risky endeavor. Here, you can indulge your curiosity without trespassing or breaking any rules. The shipwrecks in Homebush Bay have essentially been left as public art in the landscape – silently testifying to the area’s industrial past. Local authorities have embraced them as a heritage feature; you’ll even find them mentioned in tourism brochures and websites like Atlas Obscura, rather than being scrapped or removed.

Legacy of the Floating Forest

Standing on the shore of Homebush Bay, gazing at the SS Ayrfield, it’s easy to be swept up by the symbolism of the scene. This abandoned in Australia ship carries multiple layers of significance. Historically, it’s a tangible link to the era of steamships and coal-fired industries that powered Australia through the 20th century. It served in war and peace, connecting Australian resources to the world. The fact that it was left to die in the very city it served ties into the narrative of a country moving on from its old industrial identity.

Environmentally, the Floating Forest is a story of resilience and recovery. Homebush Bay was once a toxic wasteland, polluted by chemicals and industrial waste. Massive cleanup efforts around the 2000s revitalized the bay, and the flourishing of mangroves in the Ayrfield’s hull is a vivid microcosm of that larger rehabilitation. Nature has a way of healing if given the chance. The ship’s transformation into a green haven illustrates how life can triumph in the most unlikely places – even inside a rusty iron carcass. It reminds us that the end of one life (the ship’s life as a man-made object) can inadvertently create a new life (an ecosystem).

Culturally and aesthetically, the SS Ayrfield has morphed into something of an accidental artwork. Photographers flock here, especially at sunrise or sunset, to capture the almost mystical image of a forest island drifting on the water. The contrast of textures – the hard, jagged rust against the soft, lush foliage – makes it a favorite subject in photography circles and travel blogs. It’s been featured in countless “world’s most amazing abandoned places” lists and slideshows, cementing its status as a world-famous abandoned ship. In a way, the SS Ayrfield has achieved more fame in its abandonment than it ever did in service. Not many coal ships get that kind of second life in the public imagination!

Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Floating Forest is the inspiration it provides to urban explorers and the public at large. It invites us to ponder the passage of time and the interplay between human activity and nature. Standing before it, you might ask: What stories could this old hull tell? You imagine the thrum of its engines and the churning of its propeller in bygone decades, now replaced by the gentle lap of water and rustle of leaves. Such reflections are exactly what fascinate those who seek out abandoned places – the sense of time frozen and nature’s quiet encroachment. The SS Ayrfield delivers this atmosphere in abundance, without the need to crawl through an old building or venture into remote ruins. It sits in plain sight, yet feels like a secret discovered.

In conclusion, the SS Ayrfield at Wentworth Point stands as an awe-inspiring convergence of history, decay, and rebirth. Built in 1911, it served diligently through wartime and peacetime, only to be abandoned in Australia as a disposable relic of a bygone era. But in that abandonment, it found a new purpose – or rather, nature found a purpose for it. Today, the Floating Forest of Homebush Bay is more than just an urban exploration hotspot; it’s a living lesson on the impermanence of human endeavors and the enduring power of nature. If you’re into urban exploring in Australia, or simply love offbeat and beautiful sights, the SS Ayrfield will not disappoint. It’s a place where you can feel the echoes of the past while witnessing the ever-growing force of life reclaiming the rust. The next time you’re in Sydney, venture out to the quiet shores of Wentworth Point and take in the view of the Floating Forest – it’s a hauntingly beautiful experience that answers a resounding “yes” to the question of whether nature truly does win in the end.

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in learning about the Haven House of Ocala, the Muynak Ship Graveyard, or the South Fremantle Power Station.

An aerial 360-degree panoramic image capturing the rusting remains of the SS Ayrfield at Wentworth Point in New South Wales, Australia. Photo by: Grae McDowell

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.