Ocmulgee River Train Swing Bridge: URBEX Guide to a Historic Railroad Giant in Lumber City, Georgia

Step into the story of the Ocmulgee River Train Swing Bridge in Lumber City, Georgia—a rusting relic of rail history that still commands attention over the slow-moving river below. Once a vital route for trains crossing the Ocmulgee, this industrial giant now draws URBEX enthusiasts and history lovers who are fascinated by its weathered steel, quiet surroundings, and haunting sense of abandonment.

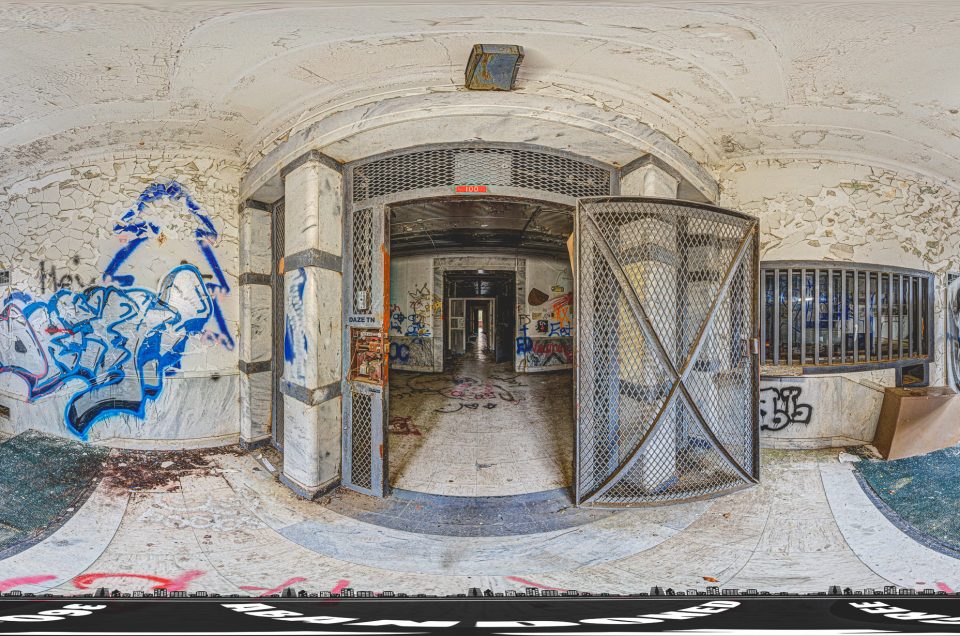

You can experience the Ocmulgee River Train Swing Bridge from every angle through an amazing 360-degree virtual tour, complete with three aerial panoramic images that offer a dramatic bird’s-eye view of the bridge and its riverside setting. Whether you’re planning your next urban exploring adventure or simply enjoy discovering forgotten places from home, these immersive visuals let you study every detail of this abandoned swing bridge in stunning clarity.

Click here to view it in fullscreen.

A Steel Giant Above the “River of Bubbling Water”

If you drive US 341 through Lumber City, Georgia, you’ll spot it almost immediately: a long, rust-red lattice of steel stretching across the wide Ocmulgee River, crowned by a weathered operator’s house perched above the water. That is the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge, a towering through-truss railroad span that has watched more than a century of river traffic, steamboat whistles, and freight trains roll by.

Perched beside the modern highway bridge, this structure is a dream subject for anyone into urban exploring in Georgia. From the riverbanks and public viewpoints you can study the geometry of the trusses, the mysterious swing span that no longer turns, and the lonely cabin where operators once lived a life suspended above the channel.

For URBEX lovers and photographers, it absolutely looks abandoned: oxidized steel, missing windows, and an operator’s shack that has clearly been out of service for decades. In reality, the story is more layered. The swing mechanism and its electrical gear are long abandoned, but the rail line itself still sees freight traffic under Norfolk Southern, making this both an active railroad bridge and a relic of a vanished river-steamboat era.

This guide dives into the bridge’s construction and opening, its operating life, the reasons its swing span fell silent, and the wider history of Lumber City and the Ocmulgee. Along the way, we’ll talk about why this place is so compelling to the URBEX community, how to enjoy it safely and legally, and what kind of stories and “scandals” hang around its riveted skeleton.

Ocmulgee River Train Swing Bridge at a Glance

Before we zoom out into the wider history, here’s a quick-reference overview of the bridge itself, based on historical and railfan sources:

-

Official name / common name: Usually referred to as the Southern Railway swing bridge or Ocmulgee River train swing bridge at Lumber City.

-

Location: Spans the Ocmulgee River between Telfair and Jeff Davis Counties at Lumber City, Georgia, parallel to US 341.

-

Railroad: Originally built for the Southern Railway’s Macon–Brunswick route; today part of Norfolk Southern’s Brunswick District.

-

Year constructed: 1928, according to Virginia Bridge & Iron Company construction records and the date plate photographed on the truss.

-

Builder: Virginia Bridge & Iron Co., a prolific early-20th-century bridge fabricator.

-

Design: Steel through-truss swing bridge, with a central pivot pier and an elevated bridge operator’s house atop the swing span.

-

Length: Around 2,800 feet in total, including long trestle approaches and the main swing span over the navigation channel.

-

Original purpose of swing: To rotate open so that tall steamboats and other river traffic could pass along the Ocmulgee/Altamaha system to and from the coast.

-

Current status:

-

Rail line: Still used by freight trains under Norfolk Southern.

-

Swing mechanism: Electrically decommissioned; the swing span is reported locked in place with its electrical components removed.

-

For URBEX and rail history fans, that combination—an active line running across a partly abandoned moving bridge—is what makes the structure so unusual.

Lumber City and the Ocmulgee: River of Timber, Cotton, and Stories

To understand why the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge exists at all, you have to understand the river it crosses. The Ocmulgee River runs about 255 miles through central Georgia, eventually joining the Oconee River to form the Altamaha River near Lumber City, before flowing to the Atlantic near Darien.

For centuries, the river was home to Indigenous communities; later, it became a critical artery for Georgia’s cotton and timber economy. The river’s name is thought to derive from Hitchiti words for “water” and “bubbling” or “boiling,” commonly translated as “where the water boils up,” which inspired the nickname “River of Bubbling Water.”

By the early 1800s, as steamboat technology matured, the Ocmulgee became one of the Deep South’s river highways. Historical accounts note that steamboats reached Macon by 1829, and by the 1830s and 1840s there was a consistent flow of vessels hauling cotton and lumber from towns like Macon, Hawkinsville, Jacksonville, and Lumber City down to coastal markets in Savannah and Darien.

Lumber City itself grew from a lumber company experiment: a group of Maine investors bought vast tracts of Southern pine land in Telfair County, built large sawmills along the Ocmulgee, and founded a settlement that took the straightforward name Lumber City. Though the initial venture wasn’t as successful as hoped, the name stuck, and the combination of river and timber made the location strategically important.

For decades, steamboats and river barges connected directly with railroad wharves at Lumber City, where cargo could transfer between water and rail. A county tourism guide notes that steamboats on the Ocmulgee made connections with the Southern Railroad here, reinforcing how this spot became a junction of river and steel.

Even today, travel pieces invite visitors to paddle the Ocmulgee near Lumber City, floating under a “historic train trestle” that once rotated to let steamboats pass, while enjoying the river’s broad bend—a section sometimes called “Big Bend.” For an urban explorer standing on the modern riverbank, the scene feels timeless: muddy water sliding past, cypress and hardwoods crowding the banks, and the bridge looming overhead like an iron fossil from the age of steam.

Rails Reach the Ocmulgee: The Macon & Brunswick Era

Long before the current swing bridge appeared, the railroad arrived. In the mid-19th century, Georgia chartered the Macon and Brunswick Railroad, a 174-mile line designed to connect Macon’s inland markets with a seaport at Brunswick. Construction stalled during the Civil War, but by the late 1860s the line finally pushed southward across central Georgia.

By September 1869, the railroad had reached Lumber City, and records note that a trestle over the Ocmulgee near Lumber City was nearing completion—the first major rail crossing at this location. The coming of that trestle helped solidify Lumber City’s role as a rail-river nexus and spurred development all along the line.

The Macon & Brunswick story isn’t just one of engineering triumph, though; it also touches darker parts of Georgia’s past. Historical research notes that after the Civil War, construction gangs on the line included workers from the convict lease system, an exploitative practice that effectively extended slavery under another name. For modern explorers, that means every spike and bridge along this route—including the later Ocmulgee River train swing bridge—sits on top of a complicated human story, not just an engineering one.

Financial trouble plagued the Macon & Brunswick Railroad, and by 1873 the State of Georgia seized the struggling line. Eventually it became part of larger systems, ultimately absorbed into the Southern Railway and later the Norfolk Southern network. Through all those corporate reshuffles, the Ocmulgee crossing remained crucial: you couldn’t get trains between Macon and Brunswick without jumping this river.

Building the 1928 Ocmulgee River Train Swing Bridge

The original 1860s wooden and early steel trestles were adequate for lighter locomotives and smaller trains, but by the early 20th century, heavier locomotives, longer consists, and more demanding safety standards pushed railroads to upgrade key river crossings. At Lumber City, that upgrade took the spectacular form of the through-truss swing bridge we see today.

Sorting Out the Construction Date

If you poke around various railfan and bridge databases, you’ll see two dates pop up for this structure: 1916 and 1928. An entry in a widely cited list of swing bridges describes a Norfolk Southern Railway bridge crossing the Ocmulgee at Lumber City as roughly 2,800 feet long and built in 1916, noting that its electrical swing components had been removed.

However, more site-specific research has settled the question in favor of 1928. Photographer and historian Brian Brown, writing for Vanishing Georgia, reports that while some sources list 1916, the construction records of the Virginia Bridge & Iron Company and a broken but readable date plate on the bridge itself both indicate a 1928 build date. An industrial history blog that compiles bridge data backs this up, noting that the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge in Lumber City was “built 1928 by the Virginia Bridge & Iron Co.”

Taken together, the weight of evidence points to 1928 as the correct construction and opening year of the present swing bridge, likely replacing an earlier trestle from the Macon & Brunswick era. (The 1916 date sometimes cited may refer to earlier work or to confusion with a different structure on the system.)

Design and Structure

The Ocmulgee River train swing bridge is a steel through-truss swing span combined with long approach trestles and additional truss panels.

Key design elements include:

-

Through-truss construction: Trains run through the trusses rather than atop them, with heavy riveted steel members forming upright sides and a lattice roof. This style was common for major railroad river crossings in the early 20th century because it provided excellent strength for heavy locomotives.

-

Central pivot pier: In the middle of the river stands a robust cylindrical pier supporting the swing span. When the bridge was operational as a drawbridge, the entire central truss pivoted horizontally around this pier to open a navigation channel on either side.

-

Operator’s house: The most visually striking feature—especially for URBEX photographers—is the bridge tender’s cabin mounted above the swing span. Historical sources and travel writers consistently mention this “bridge operator’s shed” perched atop the structure.

-

Length: Together with its trestle approaches, the bridge stretches about 2,800 feet, dominating this reach of the river.

In its prime, the structure was not just a steel crossing but a working machine: rails, gears, motors, and an operator’s living space all tied into the larger choreography of river and rail traffic.

How a Swing Bridge Like This Worked

While we don’t have a full technical manual for this specific bridge, its configuration matches standard early-20th-century swing bridge practice. Combined with local recollections and river history, it’s possible to sketch how operations probably looked when the swing span was still active.

-

Normal position:

-

Most of the time, the swing span would be aligned with the tracks, locked in place on its pivot and end bearings, allowing trains to cross uninterrupted.

-

-

Opening for river traffic:

-

When a steamboat or large vessel approached upriver or downriver, the crew would signal the bridge tender—historical accounts from the region even mention carrier pigeons being used for communication at one time.

-

The operator would stop train movements, release mechanical locks, and engage the swing machinery, once powered by electrical components that have since been removed.

-

The central span would rotate around its pivot pier, opening channels on either side so the steamboat could pass.

-

-

Closing and locking:

-

After the vessel cleared, the operator would swing the span back into alignment, re-lock it, and allow rail traffic to resume.

-

Think about that for a second from an explorer’s perspective: a person living and working in that little house above the river, coordinating trains and steamboats, keeping watch over floodwaters and fog, literally controlling whether the Ocmulgee was a highway of steel or an open river channel at any given moment.

Today, the electrical swing components have been removed and the bridge is effectively a fixed structure, but the bones of that mechanism remain in plain sight—gears, racks, and the distinctive pivot pier.

When the Riverboats Stopped Coming: Decline of Navigation and the Silent Swing

The Ocmulgee and Altamaha rivers carried steamboats for roughly a century, from the early 1800s into the early 1900s. Historical accounts speak of multiple steamboat companies operating and of a steady flow of cotton and lumber moving downriver from towns like Macon, Hawkinsville, Jacksonville, and Lumber City.

By the time the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge was built in 1928, however, river commerce was already waning. Railroads and, increasingly, paved highways were taking over freight and passenger traffic. Brown’s Vanishing Georgia piece notes that when the swing bridge was constructed, most riverboat traffic had already been rendered obsolete by the railroads that now marched along the riverbanks.

Over the decades, dredging and navigation works became less of a priority, and deep-draft riverboats gradually disappeared from this stretch of the Ocmulgee. Travel writers describing modern recreational paddling here speak of kayaks and small boats floating under the “historic train trestle” rather than commercial vessels queuing for passage.

At some point—likely mid-20th century—the cost and effort of maintaining the swing machinery no longer made sense. According to the swing-bridge listing that mentions this structure, the electrical control components were removed, freezing the span permanently in the closed position.

For modern explorers, that moment is the bridge’s “abandonment”:

-

The river navigation function is gone.

-

The operator’s house stands empty, windows broken or missing, stairs rusting.

-

The swing span no longer moves, and the machinery is a collection of dead gears and shafts clinging to the pivot.

So while trains still cross the Ocmulgee here, the swing portion of the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge is genuinely abandoned in Georgia, frozen in place as a monument to an era when riverboats and railroads had to share the same corridor.

Still in Service: Trains on the Brunswick District

Despite its weathered appearance, this bridge is not an abandoned railroad trestle in the strict sense. Multiple contemporary sources—including travel writers, local history blogs, and even Norfolk Southern’s own employee timetables—confirm that the crossing remains part of an active freight corridor.

-

A Norfolk Southern Georgia Division timetable lists a speed restriction “over Ocmulgee River Bridge,” clearly treating it as a live part of the Brunswick District line.

-

A local history blog describing Lumber City notes that the bridge, originally built by Southern Railway and now owned by Norfolk Southern, “is still used for daily rail traffic.”

-

Travel features inviting visitors to paddle the Ocmulgee describe the structure as a historic train trestle rather than a dead line, again implying it remains in use.

From a URBEX point of view, this is crucial: the bridge carries live trains. That means:

-

It is extremely dangerous to be on or near the tracks.

-

Trespassing on the railroad right-of-way is illegal and can carry serious penalties.

-

The safest and most responsible way to appreciate the structure is from public roads, legal river access points, or the water in a properly equipped boat, obeying all local regulations.

For photography, the fact that trains are still running can be a bonus. If you time things right (and keep a respectful distance from the tracks), you can capture shots of modern locomotives rolling over a structure that looks like it fell out of a 1920s engineering textbook.

Scandals, Accidents, and Ghost Stories (or Lack Thereof)

The Bigger Scandal: How the Line Was Built

The most historically documented controversy associated with this rail corridor isn’t a dramatic wreck on the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge but the labor system used to build the Macon and Brunswick line itself. Historical studies of the railroad mention that parts of the line’s construction relied heavily on the convict lease system, in which incarcerated people—disproportionately Black—were leased out as labor, often under brutal conditions.

That system has come to be recognized as a profound injustice, sometimes described as “slavery by another name.” While this scandal is tied to the railroad more broadly rather than to a single bridge, it’s part of the moral shadow that hangs over many Southern rail lines, including the one that crosses the Ocmulgee here.

Derailments and Local Lore

Social-media discussions in rail history groups mention at least one derailment involving tank cars on the Ocmulgee River bridge, with some commenters blaming vandalism for the incident. Details—like the exact date and the extent of damage—are hard to confirm from formal sources, so it’s best treated as local lore rather than thoroughly documented history. Still, it adds to the bridge’s reputation as a serious place where a small act of negligence can have big consequences.

Meanwhile, Vanishing Georgia’s broader coverage of the region touches on unsolved deaths and mysterious local stories from the 1930s elsewhere along the Ocmulgee corridor, which some locals fold into the atmosphere of the river valley as a whole. None of these are definitively linked to the swing bridge itself, but if you’re someone who loves a little ghost-story ambiance with your URBEX, the Ocmulgee supplies plenty of raw material.

The important takeaway: there is no widely documented catastrophic collapse or infamous wreck tied specifically to this bridge, but the line has seen its share of accidents and tragedies over more than a century of operation, and its origins are tied to exploitative labor practices.

Why This Bridge Is a URBEX Favorite

From a pure URBEX perspective, the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge checks a lot of boxes:

-

Massive, photogenic structure:

-

The span is long, imposing, and visually complex, with repeating truss patterns and bold silhouettes against the sky.

-

-

A clearly abandoned component (the swing system):

-

The operator’s house is empty.

-

The swing machinery is inactive.

-

The steamboat era it once served is gone.

-

-

Strong historical context:

-

It sits where two major rivers combine into the Altamaha, linking inland Georgia to the coast.

-

It’s tied to the story of lumber, cotton, riverboats, convict labor, and the rise of Southern rail.

-

-

Access to safe public viewpoints:

-

Official travel articles encourage visitors to kayak the Ocmulgee and pass under the “historic train trestle.”

-

-

“Abandoned in Georgia” aesthetic without full closure:

-

From the outside, the structure looks like many classic abandoned in Georgia sites: rust, isolation, and fading industrial hardware.

-

Yet trains still rumble across, which adds a sense of living history rather than pure ruin.

-

For urban exploring in Georgia, that blend of abandonment and activity is special. You’re not just looking at a ruin; you’re seeing how infrastructure evolves—one part frozen in the 1920s, another part still very much doing its job.

Responsible Exploring: Safety and Legal Considerations

Because this is an active railroad bridge, a responsible URBEX guide has to say this plainly:

Do not walk on the bridge, the tracks, or the railroad right-of-way.

Trains are quiet, fast, and difficult to outrun. The bridge has no safe refuge areas for pedestrians, and a misstep could be fatal. In addition, railroad trespassing is illegal in Georgia and can lead to fines or arrest.

Instead, consider these safer, legal ways to experience the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge:

-

From public roads:

-

US 341 and other nearby roads offer sweeping views of the bridge, especially where the highway runs parallel to the river.

-

-

From public river access:

-

Official guides highlight kayaking and canoeing the Ocmulgee near Lumber City, including routes that pass under the historic trestle. Always launch from legal access points and obey all local regulations.

-

-

From the water (with gear):

-

If you have a boat or join a guided paddle, you can float directly under the swing span. Wear a proper PFD, secure your camera gear, and be aware of currents and water levels.

-

Suggested Gear for a Safe, Legal Visit

For a typical URBEX-style photo outing that respects the law:

-

Telephoto lens (70–200mm or longer): Great for compressing the trusses and isolating details of the operator’s house from a safe distance.

-

Wide-angle lens: Useful if you’re on the water or at a riverside access area and want to capture the whole span and modern highway bridge together.

-

Polarizing filter: Helps cut glare off the river and deepen the sky.

-

Tripod (where practical): Especially handy at sunrise or sunset from public overlooks.

-

PFD and dry bag: If you’re paddling, treat the photography as secondary to safely managing your boat.

Combine that with a respect-first attitude—no trespass, no vandalism—and you’ll be able to enjoy the site in the true spirit of URBEX: documenting, not damaging.

Reading the Bridge: Details to Look For

When you’re standing at a legal vantage point near the bridge, slow down and “read” it like a piece of machinery frozen in mid-motion. Here are some details to hunt for with your lens or binoculars:

-

The pivot pier:

-

Look for the central cylindrical pier with a broader, flared base. That’s the heart of the swing mechanism—everything else on the main span once revolved around it.

-

-

The operator’s house:

-

Note how it sits slightly off-center on the swing span, with windows on all sides. Imagine living there, monitoring both river and rail.

-

-

Balance of the truss panels:

-

The truss segments on either side of the pivot are carefully arranged so the span balanced during rotation.

-

-

Relics of machinery:

-

From some angles you may spot gear teeth, shafts, or locking mechanisms that once secured the bridge in position.

-

-

Interface of old and new:

-

Contrast the rusty trusswork with the clean concrete of the modern highway bridge alongside it. The two structures tell a story of evolving transportation priorities.

-

This kind of detail-spotting is what makes URBEX rewarding even when you never have to set a foot on restricted territory.

The Ocmulgee Corridor: Beyond the Bridge

One bonus of planning a trip around the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge is that the river corridor itself is rich in historic and natural sites.

-

The Ocmulgee forms the entire southern boundary of Telfair County, and local tourism materials emphasize its role in everything from early timber to record-breaking fishing tales, including the world-record largemouth bass caught at nearby Montgomery Lake in 1932.

-

The river’s role in Indigenous history, plantation agriculture, and later railroad-driven development is documented in state encyclopedias and NPS studies, making it one of Georgia’s most historically layered waterways.

If your style of urban exploring in Georgia includes abandoned schools, factories, or hospitals, the Ocmulgee corridor offers extra context: many of those forgotten places shipped their lumber, cotton, or manufactured goods along the same routes served by this bridge, either upstream or downstream.

Bringing It All Together: A Living Relic of Rail and River

So where does the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge fit in the broader picture of URBEX and abandoned in Georgia sites?

-

It’s not a fully abandoned line—freight trains still cross daily.

-

It is a decommissioned river draw, with an empty operator’s house and dead swing gear recalling an era when steamboats and trains had to negotiate for right-of-way on the same river.

-

It sits in a landscape where timber barons, convict labor, steamboat captains, and railroad engineers all shaped the land—and where their choices, good and bad, echo through the rust today.

For urban explorers, that makes this bridge a kind of open-air textbook. Viewed from legal vantage points, it offers:

-

Industrial design and engineering history.

-

A case study in how infrastructure evolves and partially falls out of use.

-

A visually striking symbol of how rivers and railroads once cooperated—and competed—to move the South’s economy.

If you’re building a personal itinerary of urban exploring in Georgia, the Ocmulgee River train swing bridge belongs right alongside your crumbling mills, forgotten schools, and derelict hospitals. Just remember that this one is still carrying trains, and treat it with the respect a living piece of infrastructure deserves.

Final URBEX Checklist for the Ocmulgee River Train Swing Bridge

-

✅ Understand that the line is active; stay off the tracks and bridge.

-

✅ Use public roads and legal river access for your viewpoints.

-

✅ Bring appropriate gear—PFD, telephoto lens, and patience.

-

✅ Take only photos, leave only ripples in the water and footprints on public ground.

-

✅ Treat the site as both a historic relic and a working asset to the community.

Do that, and you’ll walk away not just with killer images, but with a deeper appreciation for how river, rail, and human ambition all collided at this quiet bend in Georgia’s “River of Bubbling Water.”

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in learning about the Super 8 by Wyndham Asheville-Biltmore in North Carolina, the Antioch Baptist Church in Georgia, or the Remington Arms Munitions Factory in Connecticut.

An aerial 360-degree panoramic image capturing the Ocmulgee River Train Swing Bridge in Georgia. Photo by the Abandoned in 360 URBEX Team

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.