Exploring the Abandoned Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory in Bydgoszcz, Poland

The Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory in Bydgoszcz, Poland, stands as one of the region’s most fascinating remnants of industrial history. This vast complex once played a pivotal role in wartime production and has since transformed into a hauntingly beautiful site of decay. For urban explorers, its crumbling walls, overgrown pathways, and massive structures offer a rare opportunity to step into the past while capturing the eerie silence that now fills its abandoned spaces.

Thanks to modern technology, you don’t need to travel to Poland to experience its atmosphere. You can explore the Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory virtually through the incredible 360-degree panoramic images available on Google Maps Street View. These immersive visuals provide a unique perspective, allowing you to navigate the forgotten corridors and towering buildings of this once-powerful industrial site—all from the comfort of your screen.

Photo by: Tomasz Sudoł

Photo by: Tomasz Sudoł

Hidden deep in the forests of Bydgoszcz, Poland, lies one of the most intriguing abandoned sites in Poland: the Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory. This massive industrial complex, now largely in ruins, was once a top-secret munitions plant fueling the Nazi war machine during World War II. Today, it stands as a haunting reminder of history and a tantalizing destination for urban exploring in Poland. In this blog post, we’ll journey through the factory’s storied past – from its opening year and years of operation to the activities that took place within its fortified walls – and discover how it came to be abandoned. With an informative yet friendly tone, we’ll also delve into the thrill of exploring this abandoned giant, blending historical insight with an adventurous spirit that urban explorers crave.

A Secret WWII Explosives Plant: History of Bromberg DAG Factory

The Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory (known in German as DAG Fabrik Bromberg) was established during World War II under a veil of secrecy. Bromberg is the historical German name for Bydgoszcz, reflecting the city’s status after Nazi Germany annexed the region in 1939. The factory was part of the Dynamit Aktiengesellschaft (DAG) conglomerate – a company originally founded by Alfred Nobel (inventor of dynamite) back in the 19th century. By the late 1930s, DAG had become a key supplier of explosives to the German military, and the Nazi government sought to expand its arms production rapidly in preparation for war.

Founding and Construction (1939–1942)

Year Opened: The decision to build a giant munitions factory near Bydgoszcz was made immediately after the German invasion of Poland in 1939. The site on the southeastern outskirts of the city was chosen for its perfect secrecy and strategic location – a dense pine forest far from prying eyes, yet close to major rail lines and the Vistula River. Construction began in late 1939, and the Bromberg DAG factory was rapidly developed over the next few years. By 1942, the first explosives and ammunition were rolling off the production lines.

Scale and Secrecy: The Bromberg factory was truly colossal in scale. Sprawling over 23 square kilometers of forest (8.9 sq mi), it was the second-largest of all DAG factories, surpassed only by a 35 km² sister plant in Christianstadt (now Krzystkowice). More than 1,500 buildings were erected, interconnected by 360 km of roads and 40 km of railway tracks within the complex. The project included everything a self-sufficient city would need: production halls, laboratories, power plants, water wells, sewage systems, workshops, warehouses, fire stations, administrative offices, and even housing for staff. All of this was done under extreme secrecy. Locals were kept in the dark – the cover story was that the factory made “chocolate” or textiles, not TNT. The entire area was fenced with 35 km of barbed wire by late 1939, guarded and isolated to keep its true purpose hidden.

To minimize the risk of catastrophic explosions, the Germans employed clever industrial design. The hundreds of production buildings were small and spread out, often tucked into natural sand dunes and separated by patches of forest. Each stage of the explosives manufacturing process took place in separate structures, connected by a network of roads and underground tunnels. Buildings were staggered at different elevations and angles so that an accidental blast in one would not trigger a chain reaction through line-of-sight openings. Earth embankments and even trees planted on roofs provided camouflage and blast shielding. The site was given code names like “Torf” (Peat) and “Kohle” (Coal) for its two main sections, and to outsiders it was simply a mysterious fenced-off zone deep in the woods.

Wartime Operations and Production (1942–1945)

Once operational, Bromberg DAG became a powerhouse of Nazi munitions production. Operating from 1939 to 1945, the factory produced a wide range of explosives and propellants for the German war effort. By design, the facility was split into two large areas, each focusing on different activities in the munitions manufacturing process:

-

Western Section (DAG Kaltwasser / “Torf”) – This zone was dedicated to gunpowder and propellant production. It housed the NC-Betrieb for making nitrocellulose (an ingredient in smokeless powder), the POL-Betrieb for processing smokeless powder itself, and the NGL-Betrieb where nitroglycerin was made and mixed with nitrocellulose to form a malleable explosive dough. Here, they could even perform shooting and artillery tests on a private proving ground to quality-check each batch of powder.

-

Eastern Section (DAG Brahnau / “Kohle”) – This area focused on high explosives and final ammunition assembly. The TRI-Betrieb produced TNT and other nitro-compounds, while the DI-B-Betrieb made dinitrobenzene, a chemical used in rocket propellant (notably for the V-1 flying bomb). There was also the Füllstelle – an ammunition filling plant where explosives from the other sections were loaded into casings for bombs, artillery shells, land mines, and even small arms ammunition. In effect, Bromberg was turning out everything from gunpowder for bullets to TNT charges for bombs. By 1944, the complex was so productive that it supplied an estimated 5% of all gunpowder and explosives used by the Wehrmacht.

The output numbers were staggering. In 1944 alone, Bromberg DAG produced 13,700 tons of gunpowder, up from 7,300 tons the previous year. Nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin production ramped up into the thousands of tons as well. On a daily basis, the powder from its lines could equip 20 million rounds of rifle ammo or 26,000 medium artillery shells. The factory even conducted trials of experimental weapons: for instance, testing of rocket missiles codenamed Rheinbote was carried out using Bromberg’s propellants in nearby testing grounds.

Despite being a tightly controlled military facility, Bromberg wasn’t entirely invulnerable – Allied intelligence was aware of its existence, and the Polish resistance movement was active even within the factory’s barbed-wire perimeter. But before we explore those human stories, it’s important to grasp the human cost behind this immense production.

Forced Labor and Human Cost

Running a complex of this magnitude required a massive workforce – and much of it was forced labor. By December 1942, about 10,000 people worked at DAG Bromberg, and this number swelled to roughly 20,000 by the end of the war, including thousands of foreign forced laborers and prisoners of war. The conditions were harsh and often deadly. Tragically, between 40,000 and 50,000 POWs died from the grueling work and brutal conditions over the factory’s operation years. Many of these laborers were Poles from the local region (about half the workforce), but the rest came from all over Europe – Russians, Ukrainians, Czechs, Italians, Yugoslavs, French, and even British POWs were all put to work here under German supervision. In mid-1944, as the Nazi war effort faltered, some 1,000 Jewish women from the Stutthof concentration camp were sent to Bromberg to help load munitions and work at the nearby rail depot. The presence of these women underscores the grim reality that Bromberg DAG was not just a factory, but also part of the wider system of Nazi labor camps and Holocaust-era atrocities.

To house this enormous labor force, the Germans built 18 camp complexes around the factory. These included roughly 250 barracks (some wooden, some brick) where workers slept in overcrowded quarters – up to 100 per barrack for civilian workers, and 200 per barrack for POWs. The camps were ringed by guard towers and even dotted with 29 concrete air-raid bunkers where workers could huddle during Allied air raids. Within the factory itself, a Reich Labour Service camp and a penal camp were also established in 1943 to discipline and control the workforce.

Daily life for forced laborers at Bromberg was extremely dangerous. They handled volatile chemicals like nitroglycerin with minimal safety gear, and the constant risk of explosion or toxic exposure loomed. Medical facilities were scant – though the site did have its own clinics – and overwork, malnutrition, and abuse were common. For those who attempted to resist or escape, punishments were severe; the penal camp on-site was essentially a torture facility for “unruly” workers. The fact that so many thousands perished is a sobering testament to the inhuman conditions.

Resistance and Sabotage

Amidst these hardships, the spirit of resistance was not extinguished. The Polish underground was active in Bydgoszcz (Bromberg) from the early days of occupation, and the factory became a target for clandestine operations. As early as 1940, a secret cell of the Polish resistance (ZWZ, later known as the Home Army or AK) formed inside the Bromberg factory. Under incredibly dangerous conditions, they managed to recruit sympathetic workers and even Allied POWs into their network. A group of Polish electricians covertly drafted a detailed map of the entire complex, documenting the layout and sending this intelligence to the Home Army command. This was an extraordinary feat of espionage given the heavy security.

Sabotage was another form of resistance that took place behind the barbed wire. The largest act of sabotage in the region, known as Operation Krem, occurred on March 23, 1944. On that day, Polish operatives succeeded in causing an explosion inside the factory that killed several German engineers and disrupted operations. This bold attack – the biggest in Pomerania during the war – demonstrated that even this “fortress” of Nazi industry was vulnerable to brave saboteurs.

Additionally, a partisan group called “Darzbór” operated in the forests around the plant. Initially aligned with the AK, Darzbór not only gathered intelligence on Bromberg’s operations but also helped prisoners escape, sabotaged rail lines (like the Bydgoszcz-Emilianowo station that served the factory), and even hid downed RAF pilots. Their activities continued into the post-war years, shifting to resist the incoming Soviet-backed regime after 1945, which shows how the story of Bromberg DAG links into broader threads of Polish resistance.

By early 1945, however, the war was closing in on Bromberg from the east. The Soviet Red Army’s rapid advance would soon decide the fate of the factory.

Abandonment and Post-War Transformation

The End of WWII: German Retreat and Soviet Seizure

As the Eastern Front reached Poland in late 1944 and early 1945, the Bromberg factory’s days under Nazi control were numbered. In January 1945, with Soviet forces approaching Bydgoszcz, the German military hastily shut down the plant. Many German personnel fled, taking or destroying sensitive documents, but notably they did not have time to destroy the massive infrastructure of the factory itself. (In a similar site on the other side of Bydgoszcz – an aviation ammunition depot at Osowa Góra – retreating German troops blew up the facilities in January 1945, but the main DAG Bromberg complex was largely spared from self-destruction.) Within days, the Red Army arrived: Bydgoszcz was captured around January 24–26, 1945, effectively ending the factory’s operation.

For a brief moment, the Bromberg dynamite factory was a ghost town – its workshops silent, machinery intact but idle, and barracks empty of their former prisoners. This state didn’t last long. The Soviet Army had its own plans for this trove of industrial hardware. At the orders of the Soviet War Trophy Commission, the entire complex was stripped of its equipment as war reparations. Over the course of 1945, Soviet troops meticulously dismantled everything from heavy machinery to the two huge power plants and boiler houses. It reportedly took between 1,300 and 1,500 rail freight cars to haul away all the looted equipment – likely destined for factories in the USSR (some sources suggest it went to Ukraine). By the time they were done, Bromberg DAG was an empty shell of concrete buildings and barren workshops. The Soviets handed over the gutted premises to the Polish authorities on August 31, 1945.

Thus, the reason for its abandonment at that moment was clear: the war had ended, the Germans had lost and fled, and the victors had literally carried off the heart of the factory. What remained was a vast, quiet expanse of brick, steel, and concrete – hundreds of buildings without contents – sitting in a forest that was already starting to reclaim the land.

From Dynamite to Chemicals: The Zachem Era

After World War II, the newly liberated (and now communist-governed) Poland faced the question of what to do with this enormous industrial site. Despite the absence of equipment, the infrastructure itself was immensely valuable – 25 deep-water wells, miles of roads and rails, buildings of all kinds, and a remote secure location. So in the late 1940s, the Polish government decided to repurpose Bromberg’s remnants for peacetime industry.

By 1948, Polish authorities established new chemical factories on the site – initially called State Chemical Plants No. 9 and No. 11. In the 1950s, these were merged and became known as the Zachem Chemical Plant (Zakłady Chemiczne “Zachem” w Bydgoszczy). Zachem inherited many of the DAG buildings and infrastructure, adapting some of them for producing chemical products like plastics, paints, and fertilizers. However, the shadow of explosives manufacturing never fully disappeared: during the Cold War, parts of the old Bromberg works were secretly used to produce munitions for the Polish Army and the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact. In fact, one section of the site revived the making of TNT and nitroglycerine for military purposes – an ironic continuation of Alfred Nobel’s legacy. This portion eventually evolved into a separate company named Nitrochem. Located in the eastern part of the complex, Nitrochem became (and remains today) a specialist in explosives; it is currently one of the largest TNT producers in Europe, even supplying TNT to international ammunition manufacturers.

Despite Zachem’s efforts to reuse the site, much of the original German-built complex remained abandoned even during the communist era. Only about a quarter of the 1,000+ wartime buildings were ever repurposed for new production. The rest stood empty, slowly crumbling or being overtaken by vegetation. In 1952, an accidental explosion in one of the unused structures (a grim reminder of the volatile materials once handled there) destroyed part of a former production line. Over the subsequent decades, there were periodic attempts to utilize more of the old DAG facilities – some buildings were converted for the synthesis of plastics in the 1970s, for example. Yet many experiments failed due to outdated design or contamination, and hundreds of buildings simply decayed. Some unstable structures were deliberately demolished; rubble from blown-up buildings was dumped into nearby marshes and the Vistula River as landfill. Meanwhile, the whole area remained a high-security zone. Zachem’s operations (especially the secret military production) meant that the entire premises stayed fenced and off-limits to the public, shrouded in mystery for decades.

By the 1980s, the Bromberg site had an almost post-apocalyptic landscape in places: abandoned bunkers and warehouses hidden in thick forest, cracked concrete roads disappearing under moss, and rusting pipes snaking through trees. Only the hum of active chemical plants on the periphery and the occasional patrol of factory security hinted at the life within the fence. For the people of Bydgoszcz, the old DAG factory was nearly as secretive under communism as it was under the Nazis – a forbidden zone of which wild rumors and ghost stories were told.

Decline, Closure, and Preservation Efforts (1990s–Present)

The fall of communism in 1989 and the transition of Poland to a market economy brought big changes to Zachem. The large state-owned enterprise struggled in the new era of competition. In the 1990s, Zachem was restructured: the explosives division was split off as Nitrochem (which continued to thrive in its niche), and the remaining chemical divisions tried to modernize. Ultimately, economic pressures and environmental issues caught up with Zachem. By the early 2010s, the company was in decline, and in December 2013 the Zachem chemical plant declared bankruptcy and ceased operations. This marked the final closure of large-scale industry on the old Bromberg DAG grounds. After about 70 years of continuous industrial activity (war-related or otherwise), the site fell silent once more.

Suddenly, vast sections of the property were completely disused – truly abandoned for the first time since the war. In total, the area contained 120 km of internal roads on 300 hectares of land when Zachem closed in 2013. Concerned about safety and redevelopment, the city of Bydgoszcz stepped in to purchase portions of the land (about 19 hectares and 9 km of roads) in 2015. Part of the motive was to establish a new Industrial and Technological Park, which had actually begun on one corner of the site in 2004 and was expanding. That modern industrial park brought new businesses but also led to the demolition of some derelict WWII-era buildings to clear land.

However, local historians, urban explorers, and heritage enthusiasts were alarmed at the potential loss of such a unique historical complex. The growing interest in the history of the site, combined with the threat of losing it to development or decay, spurred action to preserve what remained. In 2005, city authorities took a crucial step by designating two protected conservation zones within the forest: one centered on the POL-Betrieb gunpowder production area, and another around the NGL-Betrieb nitroglycerin production area. These zones encompassed clusters of the best-preserved buildings and infrastructure from the old factory, effectively saving them from demolition.

Out of these efforts was born the idea to create a museum that would both safeguard the ruins and educate the public about this hidden chapter of history. By 2007, the local Leon Wyczółkowski Regional Museum had taken custody of the NGL-Betrieb zone, and plans were underway to transform it into an interactive historical park. With funding from the European Union and local government, work progressed to adapt a handful of the abandoned buildings into a safe and engaging attraction. In 2011, the Exploseum opened its doors – a museum complex that represents about 1% of the original factory area (eight buildings plus connecting tunnels) that have been fully renovated. The rest of the site, however, remains largely unrestored: an open-air collection of ruins slowly being reclaimed by nature, which is exactly what draws adventurous explorers.

Before we put on our hard hats and venture into the ruins, let’s take a closer look at the Exploseum, since it offers a window into the past and present of the Bromberg factory in a way that’s accessible to anyone.

The Exploseum: From Arms Factory to Interactive Museum

Today, the most accessible way to experience the Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory is via the Exploseum, an open-air and underground museum dedicated to the history of the site. Opened in July 2011, Exploseum has quickly become one of Bydgoszcz’s premier attractions, especially for history buffs and industrial heritage fans. It even earned a spot as an anchor point on the European Route of Industrial Heritage, underscoring its significance as a cultural landmark.

What is the Exploseum? In essence, it’s a museum built into the preserved ruins of the nitroglycerin production complex (NGL-Betrieb) of DAG Fabrik Bromberg. Rather than constructing new buildings, the museum creators refurbished seven old production buildings and one bunker, leaving their industrial character intact. These structures are connected by nearly 2 kilometers of underground and overground tunnels, forming a continuous visitor route that winds through the forested site. As you walk through dim corridors and across elevated walkways, you truly get the feeling of stepping back in time to the 1940s.

Inside the Exploseum’s tunnels and chambers, modern exhibits bring the factory’s story to life. The museum’s themes cover both technology and human history. On one hand, you can see how nitroglycerin was made: the actual steps of the process are explained where they happened, with displays of production equipment, diagrams, and even reconstructed machinery. (The Exploseum features a re-created WWII-era nitroglycerine production line among its exhibits.) On the other hand, equal attention is given to the people who worked and suffered here. Multimedia displays and artifacts reveal the daily life of forced laborers, telling the personal stories behind the statistics. You’ll learn about the various nationalities of prisoners, see the crude tools they used, and read accounts of sabotage operations like Operation Krem – all set against the very walls where these events unfolded. One large hall even delves into the broader history of armaments and explosives, placing Bromberg in context from the 15th century up through World War II.

Walking through Exploseum, it’s hard not to feel a mix of awe and somber reflection. The concrete halls echo with sound effects and historical narration. In one room, you might hear the drone of wartime machines; in another, the voices of prisoners recounting their experiences (via recordings or written testimonials). The museum also showcases the biography of Alfred Nobel and the rise of Dynamit Nobel AG, linking the site’s story back to the inventor of dynamite. By the end of the 2 km trail, visitors come away with a comprehensive understanding of how this one factory was a microcosm of WWII – combining cutting-edge technology, massive industrial might, and extreme human tragedy.

Recognition and Reach: The Exploseum has received numerous awards for heritage preservation and museum innovation. It’s particularly praised for its blend of authentic environment with interactive education. As an adventurous visitor, you can don a hardhat and explore dark corridors with a flashlight (guided by marked routes, of course), giving the feel of urban exploration but in a controlled, safe manner. Since its opening, the museum has drawn tourists from around the world, not just local school groups. Within the first few years, over 130,000 people visited Exploseum – a testament to its popularity. This is quite amazing considering just a decade or two ago, this entire area was off-limits and virtually unknown to the public.

For urban explorers who usually avoid guided tours, Exploseum might still be of interest because it grants access to places that would otherwise be sealed off. That said, the true allure for many explorers lies beyond the museum’s boundaries – in the untamed expanse of the remaining factory ruins.

Urban Exploration in the Ruins of Bromberg DAG

For seasoned urban explorers, the Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory is nothing short of a Holy Grail of urban exploring in Poland. It combines vast scale, historical significance, and an eerie beauty that only abandoned industrial sites possess. While the Exploseum covers a small curated portion, the majority of the 23 km² site remains in an abandoned state – a playground for those willing to venture (and ideally, follow legal guidelines) beyond the beaten path.

The Site Today: What Remains?

Decades of abandonment and partial reuse have left the Bromberg DAG site a patchwork of conditions. In some places, you’ll find relatively intact buildings: sturdy brick structures like power plant halls, bunkers with walls a meter thick, or concrete warehouses still standing tall. In other areas, only ruins remain: roofless shells covered in ivy, foundations swallowed by earth, or the skeletal remains of steel frames. The forest has aggressively reasserted itself, with pine and birch trees growing up through cracks in asphalt and birds nesting in crumbling eaves.

Notably, the POL-Betrieb (gunpowder) area, which lies in the central part of the complex, retains a remarkable ensemble of buildings. Eighteen structures there are arranged in a circular layout – part of an original production line design – and although weathered, they collectively show the full sequence of a gunpowder factory. In fact, these were preserved as part of the conservation effort, and some still contain old machinery like giant mixing drums, presses (nicknamed “Mammoth” presses due to their size), and conveyors. It’s an open-air time capsule of 1940s technology (with a bit of 1950s Polish modifications here and there).

Elsewhere, explorers can find the remains of laboratories (smashed beakers and tiles might hint at their past), administrative offices (with peeling paint and occasional faded German signage), and miles of underground tunnels that once carried pipes and cables. These tunnels, some accessible through broken entrances, are a big draw – they connect many buildings and bunkers, making it possible to walk considerable distances below ground. However, they are also very dark, often flooded in parts, and can be confusing to navigate without proper equipment.

One haunting spot is the ruined power plant (EC III) building. Though stripped of its turbines long ago by the Soviets, the high brick walls and empty window frames of this powerhouse loom like a cathedral in the woods. It was once the heart of the factory’s energy supply, running non-stop until January 1945. To stand in its deserted shell is to feel the abrupt silence that fell when the war’s tide turned.

Scattered throughout the forest are also more personal remnants: the collapsed barracks of forced labor camps, a moss-covered concrete signpost here, a chunk of railway track there, even an occasional rusty helmet or barrel. Each artifact whispers of the lives that passed through – the engineers, the prisoners, the soldiers.

An Aura of Mystery and Adventure

For a long time, even after the war, locals could only fantasize about what lay inside the Bromberg factory zone. It was “surrounded by an aura of mystery” and heavily guarded. Yet, that mystique only made the site more alluring. For many years, hundreds of buildings connected by tunnels were explored in secret by lovers of technology and military history. These early urban explorers – sometimes former Zachem workers, sometimes curious youths slipping past fences – mapped out the hidden treasure trove of structures. They swapped tips on which fence holes led to the old nitroglycerin halls, or where one could find a forgotten stash of documents. Their clandestine forays kept the legend of Bromberg DAG alive.

Today, with the main gates no longer patrolled and parts of the fence down, the site is more accessible than it’s ever been. But make no mistake: exploring here is still an adventure that should be done with caution. The area is abandoned but not entirely benign. Hazards include unstable buildings (floors or roofs could collapse), leftover chemical contamination in some soil or basements (after all, explosives and chemicals seeped in for years), and possibly unexploded ordnance (though most was cleared, one never knows in a place that handled mines and bombs). Additionally, Nitrochem’s active facilities on the eastern edge are strictly off-limits – urban explorers must be careful not to trespass on the live factory grounds, which are usually clearly marked and separated.

That said, for those who come prepared – with good boots, flashlights, respirators if entering dusty confined spaces, and of course, permission if required – Bromberg offers an unparalleled urbex experience. Imagine walking down a long overgrown road, where every few hundred meters a bunker peers from behind trees, or climbing a rusted ladder onto the roof of a bunker to survey an endless sea of green pierced by concrete ruins. In spring and summer, the forest is eerily quiet except for birds, giving the sense that nature has finally reclaimed what was once a hive of destructive activity. In autumn, mists curl around the old cooling towers, and one can almost see ghostly figures trudging to work in the half-light of dawn (such imagery fuels many local ghost stories).

For photographers, the site is a dream: stark industrial geometry juxtaposed with wild vegetation makes for stunning shots. Light filters through bombed-out ceilings onto piles of debris, creating dramatic scenes. Many urban explorers have published photo essays of Bromberg DAG’s industrial interiors and tunnels, sharing glimpses of control panels frozen in time or endless corridors that vanish into darkness. There’s a sense of stepping into a time warp – one moment you’re in modern Poland, the next you’re standing where wartime engineers once stood, the walls still bearing their scribbled notes in German.

Tips for Urban Explorers

If you’re planning to explore the Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory (outside of the Exploseum tourist route), here are a few tips and highlights to keep in mind:

-

Do Your Homework: Research the layout beforehand. Old maps or satellite images can help you identify key zones like POL-Betrieb or the power plant. Knowing where the protected museum area is (to avoid accidentally breaking into an exhibit!) and where Nitrochem’s active area lies is crucial.

-

Safety First: Wear sturdy footwear and consider a helmet for falling debris. A high-powered flashlight or headlamp is a must for the tunnels and indoor areas. It’s wise to go with a buddy – the site is vast and getting lost or injured alone would be dangerous.

-

Highlights to See: Don’t miss the circular gunpowder buildings of POL-Betrieb – the arrangement of the 18 buildings is unique and you can imagine the production cycle as you move from one to the next. The underground passages connecting NGL buildings (near the Exploseum area) are also fascinating if accessible, showcasing the hidden arteries of the complex. If you find the remains of the worker camps (look around the peripheries near Szpitalna or Hutnicza streets), you’ll see the outlines of barracks and perhaps the storm shelters built for the laborers, which bring home the human aspect. Finally, the scenic forest dunes in the southern part of the site not only provided safety from explosions but today offer peaceful natural landscapes – a surreal contrast with the ruined factories scattered among them.

-

Respect the Site: This location is a memorial as much as it is an adventure playground. Countless individuals suffered or died here. While exploring, it’s important to show respect – do not vandalize or loot remnants, and if you encounter any plaques or memorials (the Exploseum area has memorial signs), take a moment to reflect. Urban explorers have been instrumental in documenting and thereby preserving the memory of places like Bromberg DAG, so maintaining that respect keeps the community in good standing.

-

Legal Access: Consider visiting the Exploseum museum first. It’s inexpensive and offers guided tours, which can give you a wealth of information to enrich your exploration. The museum guides might even point out areas visible from the tour that you can later photograph on your own. For the off-limits areas, enforcement is not what it used to be, but occasionally security or police patrol parts of the site (especially after some accidents in the past). Make sure you’re not crossing into clearly marked no-entry zones. In recent years, local authorities have been more open to the idea of heritage tourism here, but it’s always best to stay safe and within the law as much as possible.

Conclusion

The Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory in Bydgoszcz is a place where history and exploration converge. Opened in 1939 amid the storm clouds of war and operating through to 1945, it played a pivotal role in the conflict – a hidden city of explosives that fueled destruction across the front lines. Its story continued post-war through abandonment, Cold War resurrection as “Zachem,” and final decline back into silence. The reasons for its abandonment are layered: the end of World War II made its original purpose obsolete, the Soviet removal of equipment left it an empty shell, and changing times eventually shuttered its later incarnations. Yet out of that abandonment has come a different kind of value. The site stands today not only as one of the largest abandoned industrial complexes in Poland, but as a monument to history – preserving the memories of both innovation and suffering.

For urban explorers, Bromberg DAG offers an adventure like no other: the chance to walk through a colossal time capsule, to feel the weight of history on your shoulders as you navigate dark tunnels, and to experience the eerie beauty of decay entwined with nature. For historians and casual visitors, the Exploseum provides a way to engage with this heritage safely and informatively, peeling back the layers of secrecy that once surrounded the factory.

In a broader sense, the Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory reminds us of the vast industrial efforts behind World War II and the human lives entangled in those efforts – from brilliant chemists and engineers to enslaved laborers and resistance fighters. As you explore its abandoned halls or immersive museum exhibits, you can almost hear the echo of dynamite blasts and the whispers of those who toiled here under guard. It’s a sobering, fascinating, and ultimately rewarding experience.

Whether you are drawn by the historical significance or the thrill of exploration, the ruins in the Bydgoszcz forest await with stories to tell. The Bromberg factory is more than just abandoned in Poland – it’s a surviving witness to a turbulent past and a symbol of how places can transform and find new meaning over time. Pack your curiosity (and your flashlight), and venture into this forgotten dynamite factory – an adventure through history and a journey into the heart of urban exploration.

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in the following, Anything and Everything Store in central Florida, the SS Ayrfield in Australia, or the The Tower of Vallferosa in Spain.

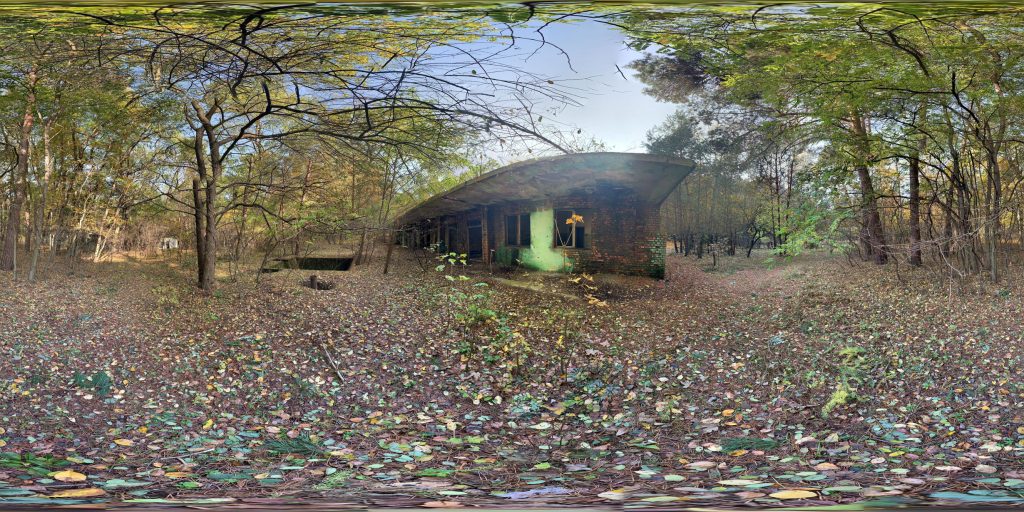

A 360-degree panoramic image captured at the Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory in Poland. Photograph by: Tomasz Sudoł

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.