Rivers State Prison: Exploring an Abandoned Georgia Prison in 360°

Click here to view it in fullscreen.

About Rivers State Prison

Rivers State Prison in Milledgeville, Georgia is an abandoned prison complex that captivates urban explorers with its deep history and eerie, time-worn atmosphere. Once a part of the vast Central State Hospital campus, this defunct penitentiary now stands quiet behind rusting fences and watchtowers, its empty corridors and former cells frozen in decay. Abandonedin360.com offers a unique window into this abandoned site – including immersive 360-degree panoramas that let you virtually walk through the prison’s crumbling halls and courtyard without ever trespassing. For Urbex enthusiasts and history lovers, Rivers State Prison provides an intriguing blend of architectural significance and haunting abandonment that’s both educational and adventurous.

On Abandonedin360.com, you can explore Rivers State Prison through a detailed 360° virtual tour, experiencing the forsaken cellblocks and shadowy tunnels at your own pace. The interactive tour brings to life the peeling paint, rusted bars, and encroaching vines in high definition, allowing urban explorers to appreciate the site’s hidden details safely and legally. Whether you’re drawn by the prison’s storied past or its photogenic decay, this digital experience offers an urban exploration of Rivers State Prison like no other – all from the comfort of your home. Abandonedin360’s mission is to document places like this in 360 degrees, preserving history and satisfying curiosity while emphasizing respect for the law and personal safety.

History of Rivers State Prison

Rivers State Prison was not originally built as a penitentiary at all – its story begins as part of Central State Hospital, Georgia’s historic mental health asylum. In the late 1930s, Central State Hospital in Milledgeville faced severe overcrowding and outdated facilities; its patient population had swelled to over 7,000, far beyond the campus’s intended capacity. In response, Governor Eurith “Ed” Rivers spearheaded a massive expansion project in 1938–1940 to modernize the hospital grounds. Using New Deal funds (WPA/PWA), the state constructed a cluster of large brick buildings on a 132-acre tract of hospital land to alleviate overcrowding. This included three H-shaped dormitory buildings, a T-shaped building, and a dedicated tuberculosis hospital complex, all connected by an underground tunnel system. When completed by the end of 1940, the new medical complex was hailed as one of the most modern, best-equipped tuberculosis hospitals in the nation, even surpassing Georgia’s own TB sanatorium in Alto in capacity. In honor of the governor who championed the project, the buildings were named the Rivers Buildings – a namesake that would later lend itself to the prison’s title.

Key Facts at a Glance:

-

Built / Opened: 1939–1940 (as part of Central State Hospital expansion)

-

Original Use: State-of-the-art tuberculosis hospital and mental health dormitories (Central State Hospital)

-

Architects: Robert & Company (Atlanta-based architects/engineers, commissioned by Gov. Rivers)

-

Named For: Governor E. D. Rivers (Georgia governor 1937–1941, who funded the construction)

-

Conversion to Prison: Early 1980s (vacant hospital buildings repurposed due to state prison overcrowding)

-

Prison Capacity: ~600 inmates (opened to relieve jam-packed county jails)

-

Closed / Abandoned: October 2008 (due to aging infrastructure and statewide prison realignment)

-

Location: Central State Hospital Campus, Milledgeville, Georgia (Baldwin County)

The Rivers Buildings served Central State Hospital for decades – initially as medical wards and dormitories for patients – but by the late 20th century they had become underutilized. Advances in tuberculosis treatment and changes in mental health care meant these massive buildings were no longer needed for their original purpose. By 1981, the Georgian government saw an opportunity: the state’s prison population was overflowing (with over 1,300 convicts languishing in county jails) while these sturdy brick structures sat largely vacant. In March 1981, Georgia’s Department of Offender Rehabilitation requested $3 million to retrofit the empty Rivers complex into a prison, aiming to house about 600 inmates in Milledgeville. The funding was approved, and the former hospital halls were soon transformed into Rivers State Prison, a medium-security facility under the Georgia Department of Corrections. The repurposing was pragmatic – however, the buildings’ origins as a mental hospital dormitory meant they lacked many security features of purpose-built prisons (for example, the layout had wide open wards and large windows rather than reinforced small cells). This necessitated additional fencing, bars, and staffing to meet prison security needs.

By the early 1980s, Rivers State Prison was up and running, housing inmates in a dormitory-style setup within those historic walls. The prison quickly developed its own identity and routines. In fact, one of the first things new inmates would see upon arrival was a sign at the gate proclaiming “We work for a living.” This motto defined daily life at Rivers State Prison. Incarcerated men were kept busy with farming, maintenance, and prison industry jobs every day, and luxuries were virtually non-existent (no TVs or comforts). Discipline was rigid: prisoners had to stand at attention in military-like inspections twice a day, keep their uniforms and bunks impeccably neat, and even march in two daily four-mile walks as exercise/punishment. Life at Rivers was intentionally tough – a Spartan regime aimed at instilling order. Some inmates later recalled how strange it felt to revisit the place once free, finding these now-empty halls “kinda creepy” after years of strict routine.

During its years of operation in the 1980s and 1990s, Rivers State Prison had its share of notable incidents and local lore. Security was always a challenge given the facility’s design, and a few daring escapes made headlines. In August 1995, an inmate serving time for burglary managed to slip away from a work detail, climbing a fence and disappearing into the outside world. (He remained at large for 17 months before being recaptured by authorities in another county.) The following year, in September 1996, two teenagers being held in a juvenile unit on the prison grounds pulled off an even more audacious escape: they squeezed out of a small infirmary window, shinnied down bedsheets, hot-wired a prison van, and drove off into the night. Although they were caught within hours, the episode revealed how the old hospital layout – with its standard windows and less fortified structures – could be exploited in ways a modern prison might prevent. These stories became part of Rivers State Prison’s legacy, underscoring the unusual intersection of a healthcare campus turned penitentiary.

Abandonment and Decline

By the early 2000s, the fate of Rivers State Prison was sealed by shifting priorities and mounting infrastructure issues. The Great Recession and state budget cuts forced Georgia officials to re-evaluate all prisons, especially aging ones. An outside review of correctional facilities was commissioned in 2003 to decide where to invest resources. The writing was on the wall: Rivers State Prison, with its 60-year-old buildings and costly maintenance needs, did not make the cut. In 2008, the Department of Corrections announced that Rivers State Prison would permanently close in October of that year. This decision came as part of a larger consolidation plan – at the time, Georgia was adding hundreds of new prison beds elsewhere (including triple-bunking in newer prisons) to increase capacity more efficiently. Simply put, the old Milledgeville complex was no longer worth the expense when modern facilities could house inmates at lower cost. “Anyone in Milledgeville knows that the infrastructure at Rivers State Prison is old,” one local official noted, and the state chose to cut its losses.

The closure of Rivers State Prison was part of a rapid wave of shutdowns on the Central State Hospital campus: Scott State Prison closed in 2009, Bostick Correctional Institute in 2010, and finally the adjacent Men’s State Prison in 2011. Thousands of state jobs were lost in Milledgeville as these institutions went dark. In the case of Rivers, more than 1,100 inmates were relocated to other prisons across Georgia in the summer of 2008 as it prepared to shutter. Roughly 200 men were reassigned to nearby Baldwin County facilities, while others were dispersed statewide, and about 260 staff members were offered transfers to prisons within a 45-minute drive. When the gates of Rivers State Prison clanged shut for the last time in October 2008, it marked the end of an era. After nearly three decades as a penitentiary (and decades more as a hospital ward), the sprawling complex was left with no clear future plan.

For more than a decade after its closure, Rivers State Prison simply sat in limbo. The State of Georgia retained ownership, but with no funds allocated for demolition or redevelopment, the property slowly deteriorated. Locals driving past the old hospital grounds could only wonder what would become of the fenced-in abandoned prison, as weeds overtook the fences and the paint peeled a bit more each passing season. It wasn’t until 2019 that the site saw a brief flicker of new activity – not from new inmates or redevelopment, but from Hollywood. A film production company leased the disused prison campus and used it as a filming location for several low-budget movies. For a short time, the cellblocks and halls were filled with actors and film crews instead of prisoners. The movie magic left its mark: when the filmmakers departed, they left behind props and set pieces that only added to the prison’s creepy ambiance. Today, explorers might stumble upon fake blood splatters, rubber “zombie” dummies, and even burned-out cars strewn about the complex – remnants of horror and action scenes that were staged on the grounds. These artifacts, combined with over a decade of neglect, have made the prison even more surreal. Graffiti tags now adorn many walls, ivy and kudzu vines snake up the brick exteriors, and whole sections of the campus are choked with overgrowth. Officially, Rivers State Prison remains in a state of arrested decay, watched over only sporadically by state security patrols. Unofficially, however, it has become a magnet for curious urban explorers (and intrepid photographers) drawn to its mix of history, mystery, and atmospheric ruin.

Exploring the Rivers State Prison Ruins Today

Wandering through the ruins of Rivers State Prison today is an awe-inspiring yet sobering experience. The approach to the complex immediately sets the mood: you pass through the outskirts of the old Central State Hospital grounds – an area aptly dubbed “Renaissance Park,” where many institutional buildings sit silent. Eventually you arrive at the prison’s perimeter: looming guard towers and layers of chain-link and razor-wire fence still encircle the property, delineating what was once a strict boundary between “inside” and “outside.” The main gate, long locked, is flanked by faded signs and the remains of a security checkpoint. Just beyond, you can see the multi-story brick facades of the Rivers buildings, their windows either boarded up or shattered into dark voids. Nature is slowly reclaiming the campus – tall grasses and weeds blanket the courtyards, and young trees have sprouted in the cracked pavement of the parking lot. It’s eerily quiet except for the rustle of leaves and the occasional bang of a loose metal sheet in the breeze.

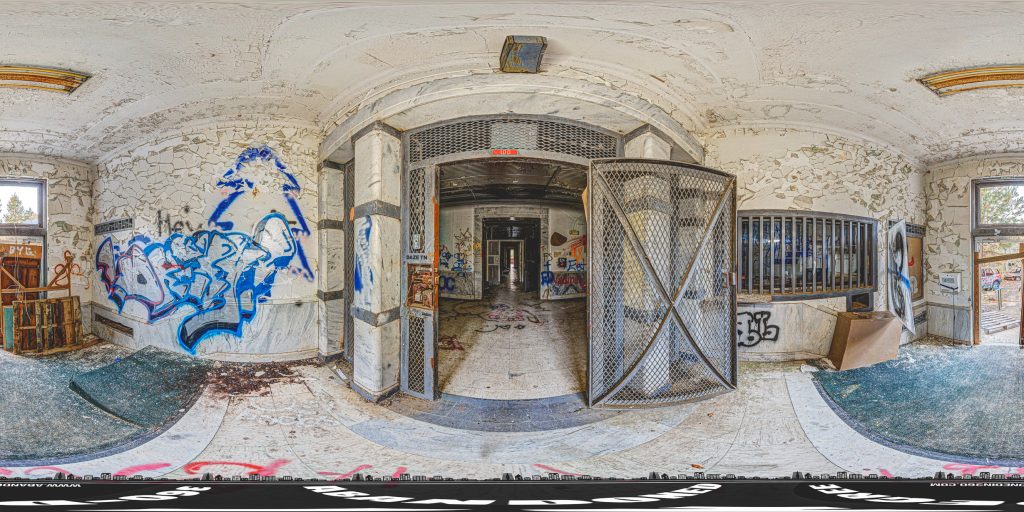

Stepping into the interior (for those few who gain lawful access, such as on sanctioned tours or through Abandonedin360’s virtual tour), you find yourself in a world frozen in 2008 and then layered with years of decay. The first thing that might strike you is the sheer scale of the place. Three massive interconnected buildings spread out in an institutional labyrinth of hallways, stairwells, and rooms. Unlike more modern prisons built with linear cellblocks, Rivers has a sprawling hospital-like layout. Long corridors stretch ahead into darkness, some lined with what used to be dormitory-style bunk rooms and others retrofit with rows of barred cells. Paint hangs in flaking sheets from the walls and high ceilings, resembling peeling wallpaper in chunks of white, green, and prison-gray. Every step echoes on the tiled floors (many sections are speckled with rubble and glass from fallen plaster and broken windows). Occasionally, your flashlight beam might catch faded signage above a doorway – hints of the prison’s operational days, like arrows pointing to the “Cafeteria” or lettering that reads “Visitation Room” or “Medical Ward.” In certain spots, you’ll notice remnants of the site’s former life as a hospital: for example, wide doorways where heavy hospital beds once rolled through, or an old nurse’s station with a pastel-colored wall. These vestiges mix with prison-era additions: here and there are heavy steel barred doors installed in the 1980s, enclosing what may have been day rooms or cell areas. The juxtaposition of healing and incarceration is palpable in these halls.

As you venture deeper, you encounter specific areas that tell their own stories. In one wing, rows of prison cells stand with their doors ajar – tiny two-man cells added during the prison conversion, each equipped with rusted metal bunks and a stainless steel toilet. The cells are claustrophobic and dark, illuminated only by narrow slits or whatever sunlight filters in from cracked windows down the hall. Personal items are mostly long gone, but you might spot the occasional fragment: a torn mattress tag, a lonely shoe, or graffiti left by someone (perhaps an explorer, or even a bored guard) marking the date of a visit. In another area, you find a large common room with a high ceiling – possibly the cafeteria or an auditorium used when this was a hospital. Here, peeling paint and mold have blurred the original purpose of the space. An upright piano with missing keys sits abandoned in a corner (an odd discovery that sparks the imagination – was it used for church services in the prison, or recreational therapy in the hospital days?). The floor is littered with papers and film props: scattered files mixed with fake “blood packets” and debris from a staged explosion scene. One wall is blackened with soot, likely from when filmmakers set off pyrotechnics to simulate a fire for a movie scene. As your eyes adjust, you notice something chilling yet intriguing: a life-sized dummy in tattered inmate garb, left behind from a zombie movie shoot, slumped against the wall. It’s easy to jump at first, mistaking it for a real person in the dim light. Moments like this blur the line between reality and imagination, making an explore of Rivers State Prison feel like walking through a horror movie set – because in some ways, it literally is.

Perhaps the most fascinating (and nerve-wracking) part of exploring Rivers is the underground tunnel system connecting the buildings. Down a flight of concrete stairs, a tunnel entrance yawns like a mouth into darkness. These tunnels once allowed hospital staff and patients to move between buildings safely, and later may have been used by prison guards to escort inmates out of the weather. Today, they are pitch-black and often partially flooded, with pipes running along the ceiling and walls crusted in mildew. Entering the tunnel, you feel the temperature drop and the air turn damp and musty. The beam of your flashlight might catch glints off something hanging – clusters of stalactite-like mineral deposits where water drips from the ceiling. The silence is profound; each footstep splashes in the puddles on the floor. Halfway through, there’s an intersection where another tunnel branch is blocked off by debris and a rusty gate. Graffiti artists have been here too, leaving tags that reflect in your light. It’s easy to get disoriented down here, so many explorers leave a trail (or just wisely stick to the main passage). Emerging in another building, you climb back up and find yourself in a different portion of the prison without ever having gone outside – a testament to the design of the complex. Exploring these tunnels is a highlight for many Urbex adventurers, but it’s also one of the most dangerous segments of the journey given the confined space and potential for poor air quality.

Throughout the prison, nature’s reclamation adds to the atmosphere. In many rooms, especially on the upper floors, you’ll find green vines snaking in through broken window frames, stretching across floors and wrapping around old light fixtures. In some spots, whole small trees or saplings are growing inside the building where the roof has given way. One former administrative office now has a collapsed ceiling open to the sky – a skylight of destruction – under which a carpet of moss and grass thrives on the damp floor. The outdoor courtyards and recreation yards are jungled with weeds up to your waist. An old basketball hoop stands crookedly in one yard, engulfed by thorny brambles. As you navigate, you might disturb a family of birds or even a raccoon that has made its home in these ruins, reminding you that wildlife has started to claim this once heavily secured human domain.

For all its desolation, Rivers State Prison has moments of serene beauty. At certain times of day, the sun will stream through cracked windows and the slits of cell doors, casting dramatic beams of light amid the dust. In a second-story cellblock corridor, sunlight filtering through iron bars paints striped shadows on the corridor’s concrete floor – a photographer’s dream shot encapsulating the essence of captivity and freedom. The combination of rich red-orange rust on steel bars, emerald-green ivy creeping over doorways, and the soft golden light of late afternoon can be unexpectedly beautiful in a place built for misery. It’s these contrasts – harsh history versus gentle natural rebirth, darkness pierced by light – that make Rivers State Prison such a compelling subject for exploration and photography.

Important: It must be stressed that despite its allure, Rivers State Prison sits on restricted state property and exploring in person is illegal without proper authorization. The site is patrolled intermittently, and trespassers could face serious consequences. Moreover, the environment inside is dangerous – a fact that becomes obvious as you navigate collapsing floors and unlit tunnels. Many urban explorers instead choose to experience sites like Rivers vicariously, through resources like Abandonedin360’s virtual tours, which provide a thorough look at the prison’s interior without the risks.

Architecture, Design & Decay

Architecturally, Rivers State Prison’s bones reflect its origin as a late-1930s institutional complex. The design is utilitarian with subtle stylistic flourishes typical of WPA-era construction. The exteriors are red-brick with stone accents, arranged in that distinctive H-shaped and T-shaped configuration that maximized light and ventilation for hospital patients. If you look at archival photos or the remaining facades, you can spot tall rectangular windows and flat roof sections that likely served as sun balconies or solariums for tuberculosis treatment (fresh air and sunlight were crucial therapy in the pre-antibiotic era). There’s a symmetry and sturdiness to the buildings – built to last, with concrete, brick, and steel that have indeed held up for over 80 years. Walking around the complex, you notice touches of Classic Revival influence: a grand front entrance with a pediment and columns on one building, and decorative brickwork patterns along the roofline of another. These hints of architectural grace are now marred by time. The grand entrance is padlocked and covered in graffiti tags, the columns spalled and cracked. Many windows are missing glass, giving the buildings a hollow-eyed look, and some frames are strangled by ivy.

Inside, the design is straightforward and institutional. Long hospital corridors branch into patient wards (later used as dormitories for inmates). High ceilings and wide hallways lend a feeling of space in some areas, while other sections – like retrofitted cell blocks – feel tight and claustrophobic. The craftsmanship of the 1940 construction is evident in details like terrazzo flooring in lobbies and heavy wooden doors (many still hanging, albeit rotting, on their hinges). In utility rooms, you’ll find hulking old machinery: for instance, a vintage boiler in the basement with ornate iron gauges, rusted but intact, which once powered heat and hot water for the complex. Nearby might be a derelict generator or switchboard panel, its levers and dials now frozen in time. These mechanical remnants speak to a bygone era of engineering and offer great photo opportunities for those fascinated by industrial design.

Of course, decay has been the ultimate architect shaping Rivers State Prison in recent years. Decades of abandonment, exposure, and occasional vandalism have created a layered patina of deterioration. Paint peels from nearly every surface – curling off plaster walls in hands-width strips and flaking from metal beams like old bark. The color palette is muted and ghostly: pale greens and institutional beiges under a powder of white paint chips. Metal fixtures have fared slightly better but are deeply corroded; rust coats the bars, hinges, and pipes, bleeding orange onto the floors beneath. In many rooms, acoustic ceiling tiles have disintegrated into mush or fallen out completely, littering the ground with chalky fragments. Water intrusion has caused sections of ceiling and upper floors to collapse, dumping heaps of sodden wood, insulation, and concrete onto lower levels. Every such collapse opens new paths for rain, accelerating the rot. Mold and mildew thrive in the damp interior, painting black and gray splotches across drywall and giving the air a pungent, earthy smell.

Vandalism, while present, is surprisingly limited mostly to graffiti and minor damage – a testament perhaps to how hidden and guarded this location is compared to more easily accessible abandonments. The graffiti ranges from elaborate colorful murals in some of the larger rooms (one wall is covered by a skillful depiction of angel wings and eyes, eerily beautiful amid the ruin) to simple tags and messages (“FREE” spray-painted on a cell door, an ironic statement). One particularly striking piece of graffiti art in a former dormitory spells out “HELL HOUSE” in dripping red letters, clearly referencing the site’s creepy reputation. Photographers visiting Rivers often find that these graffiti pieces add a stark contrast to the decayed surroundings – modern street art colliding with the prison’s historical fabric, making for uniquely poignant images.

For urban explorers and photographers, the visual appeal of Rivers State Prison lies in these very contrasts and details. The geometry of the architecture – endless rows of doorways, repetitive bar patterns, symmetrical ward layouts – provides compelling compositions for wide-angle shots. Many halls create perfect vanishing points, drawing the eye down their length toward whatever faint light glows at the far end. The interplay of light and shadow through broken windows and doorways can be mesmerizing, especially at sunrise or sunset when warm light dances through dust in the air. Close-up photography yields equally fascinating subjects: an old padlock fused with rust on a door has a story to tell, as does the fragment of a mugshot photograph someone found clipped in an intake office file cabinet (perhaps left by an officer and now curled and faded). Texture is everywhere – from crumbly paint layers and cracked leather chairs in the admin offices, to the flaky oxidation on pipes and the delicate filigree of spiderwebs that now span the corners of many rooms. Every inch of Rivers State Prison offers a lesson in impermanence and the quiet, unstoppable march of time.

Photography & Urbex Tips

Capturing the haunting beauty of Rivers State Prison through photography is a rewarding challenge. If you’re fortunate enough to legally photograph this site (or any similar abandoned prison), here are some high-level tips to keep in mind:

-

Go Wide for Grandeur: The immense scale of the prison’s architecture is best appreciated with wide-angle shots. Try shooting down long corridors or across the expanse of a cellblock room to convey depth and repetition. Centering your shot on a vanishing point (like a hallway receding into darkness) creates a powerful composition. In the 360° images on Abandonedin360.com, you’ll notice how wide panoramas capture entire rooms and corridors – similarly, a wide lens (or panoramic stitching) in the field can showcase the full environment that a normal photo might miss.

-

Focus on Details: Conversely, don’t overlook the small details that tell the story of decay. Macro or close-up photos of rusted cell door locks, peeling paint curls, or abandoned objects (such as an old typewriter or inmate uniform pieces, if any remain) can be evocative. These shots add narrative and break up a photo series visually. For example, a tight shot of the “We work for a living” sign with its paint chipping away can symbolize the prison’s philosophy fading into history.

-

Lighting and Timing: Lighting in abandoned buildings is unpredictable – Rivers has areas of deep shadow and others where sunlight pours in. Use a tripod for stability during long exposures in dark rooms or tunnels. Early morning or late afternoon light tends to be more dramatic; beams of sun coming through barred windows or roof holes create contrast and mood that midday flat lighting won’t. If you’re shooting 360° panoramas, consider taking them at different times of day to capture various atmospheres. Also, bring a powerful flashlight or portable LED panels to light-paint large dark spaces (like the tunnel or basement) for a creative effect.

-

Show Scale and Context: In a place as large as Rivers State Prison, including a human figure (perhaps a fellow explorer) in some shots can convey scale – the height of a room or length of a hall is easier to grasp with a person or familiar object present. Even without a person, you can use furniture or architecture for scale (those bathtubs and hospital beds left behind indicate the function and size of rooms). Drone photography, where legal, can also be fantastic: aerial shots illustrate how the prison sits in context with the surrounding wooded campus. Abandonedin360’s tours sometimes include overhead views that help viewers piece together the site layout; consider similar establishing shots if you’re photographing an abandoned site with permission.

-

360° Documentation: If you have the equipment, creating your own 360-degree images or virtual tour segments is an innovative way to document an exploration. A 360° camera set in the middle of a cellblock, for instance, can capture the entire environment – floor to ceiling, wall to wall. This immersive format allows viewers to later pan around and discover details as if they were standing there. It’s perfect for sharing an Urbex experience with others who can’t physically join. Abandonedin360.com leverages this technique, stitching together dozens of panoramic images so that users can “walk” virtually through Rivers State Prison and other locations. This not only preserves the site digitally for the future, but it also helps discourage others from risking illegal entry because they can see it online. As a tip, when shooting 360 panoramas in such locations, ensure your camera is steady (use a monopod or tripod), take multiple exposures if needed to handle bright and dark areas, and always double-check that you haven’t inadvertently included yourself in the frame!

Remember, whether shooting stills or 360-degree photos, always respect the site and its story. Never alter or disturb the environment for a shot – true Urbex photography embraces the authenticity of the decay. If a room is messy, capture the chaos; if a chair is oddly placed, leave it that way (it likely tells a story). The goal is to document, not to stage or interfere.

Safety, Legal & Ethical Disclaimer

Exploring abandoned places like Rivers State Prison can be dangerous and is often illegal without permission. Abandonedin360.com does not encourage trespassing – instead, we promote appreciation of these sites through photography and virtual exploration. Here are critical safety and ethical points for would-be urban explorers:

-

No Trespassing – Get Permission: Rivers State Prison is on state property and closed to the public. Entering without explicit permission is trespassing, which is against the law. Always obey posted signs and property laws. The content here is provided for historical interest and virtual exploration only. Do not attempt to visit illegally. Law enforcement can and will prosecute intruders, and a curiosity is not worth a criminal record.

-

Physical Hazards: Abandoned structures are inherently unsafe. At Rivers, as in many old buildings, floors may be weakened by rot, ceilings could collapse at any time, and there may be exposed nails or broken glass everywhere. Environmental hazards like asbestos, lead paint, and mold are common in structures from this era. If you ever do enter any abandoned site with permission, wear appropriate safety gear – sturdy boots, gloves, a hard hat, and a respirator or mask – and never go alone. In places like tunnels, poor air circulation can be a real danger (pockets of bad air or even toxic gases). Always have multiple light sources and an emergency plan. One misstep in a place like this could be fatal.

-

Respect the Site (Leave No Trace): The Urbex community follows a crucial rule: take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints. Do not vandalize, graffiti, or steal from abandoned sites. Unfortunately, Rivers State Prison has suffered from some vandalism over the years – adding to the damage and making access tighter for everyone. Never break doors or windows to gain entry, never trash the place or litter, and absolutely do not remove any artifacts. Preserving these locations as they are is in everyone’s interest. The goal is to document and admire, not defile.

-

Privacy and Community: Abandoned places sometimes hold personal information or sensitive items (for example, in some sites, old patient or inmate records might still be found). If you encounter documents or photos, be respectful – don’t publish identifiable personal data. Additionally, be mindful of the communities around abandoned sites. In Milledgeville, for instance, these hospital and prison closures had a big impact on locals. Be polite and low-profile when photographing exteriors or flying drones, as not to disturb or alarm residents. It’s better to connect with local historical societies or Urbex groups to learn the etiquette and latest conditions of a site before visiting.

Abandonedin360.com provides 360° tours and images as a safe alternative to physically venturing into dangerous locations. We want to keep explorers safe and protect these fragile remnants of history. Enjoy the thrill of discovery online, and never put yourself or the site at risk.

Conclusion

From its origin as a cutting-edge hospital ward in the 1940s to its final days as an overcrowded penitentiary in the 2000s, Rivers State Prison encapsulates a remarkable slice of Georgia’s history. Today, its abandoned halls stand as a monument to changing times – the echo of clanging prison gates and hospital gurneys replaced by silence and the soft whispers of nature reclaiming its space. For urban explorers and history enthusiasts, Rivers State Prison is a poignant and visually arresting destination, offering lessons in architecture, resilience, and decay. Through Abandonedin360’s virtual tour and photographs, anyone can safely appreciate the atmosphere of this forgotten site: the way the light falls through barred windows, the stories etched in every piece of peeling paint, and the profound solitude of a place that once teemed with life.

Rivers State Prison remains a focus key example of why we explore and document abandoned places – it’s not just about decay, but about uncovering the layers of human experience and societal change that sites like this represent. As you finish this virtual exploration, we encourage you to explore more abandoned locations on Abandonedin360.com. From other remnants of Milledgeville’s Central State Hospital complex (like the old Men’s State Prison and Scott State Prison) to distant derelict factories and forgotten homesteads, there’s a whole world of abandoned wonders waiting to be discovered – safely and responsibly. Rivers State Prison may be quiet now, but its story continues to captivate and educate through the lenses of urban explorers.

Stay curious, stay safe, and happy exploring – whether out in the field or through a 360° screen!

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in learning about the Powell Building at the Central State Hospital, the Washington Building at Men’s State Prison just down the street from Rivers State Prison, or the Santa Fe Railroad Terminus at Point Richmond in California.

A 360-degree panoramic image captured at the abandoned Rivers State Prison in Milledgeville, Georgia. This photo shows the entrance to the Rivers South Building. Photo by the Abandoned in 360 Urbex Team.

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Equipment used to capture the 360-degree panoramic images:

- Canon DSLR camera

- Canon 8-15mm fisheye

- Manfrotto tripod

- Custom rotating tripod head

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.