Abandoned New York City Farm Colony: Staten Island’s Historic URBEX Treasure

Step into the history of the New York City Farm Colony, a once-thriving institution hidden within Staten Island’s woodlands. This site, with its haunting remnants of past decades, offers a rare opportunity for urban explorers to witness the slow passage of time and the echoes of a bygone era. Once alive with activity, the colony now stands as a fascinating reminder of New York’s social and cultural history.

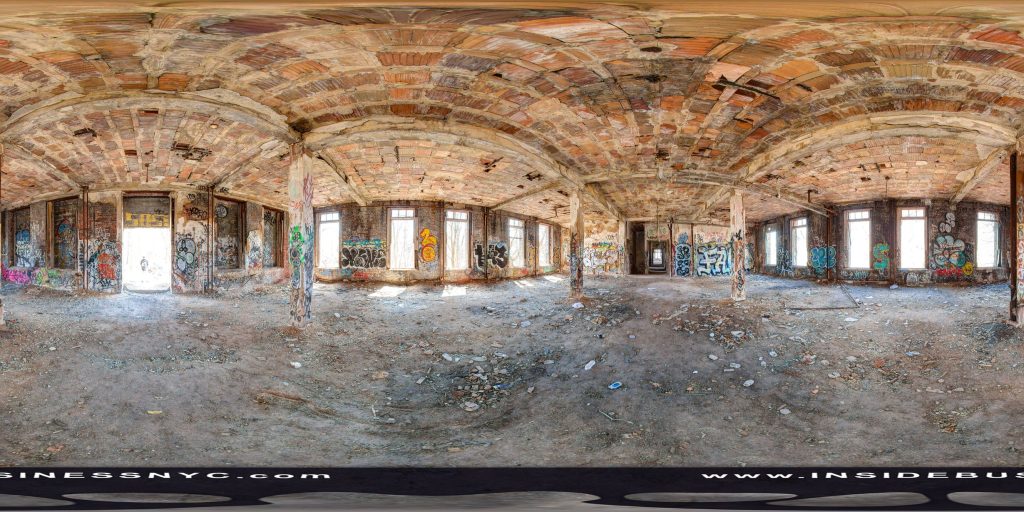

Today, the abandoned New York City Farm Colony draws explorers eager to uncover its decaying structures and forgotten spaces. Through the incredible 360-degree panoramic images available on Google Maps Street View, visitors can gain a vivid look at the grounds without stepping foot inside. For those passionate about URBEX and urban exploring in New York, this location provides both a digital gateway and a glimpse into the enduring allure of abandoned places.

Photos by: Black Paw Photo

Photos by: Black Paw Photo

The New York City Farm Colony is one of the most intriguing sites abandoned in New York, a sprawling poorhouse-turned-ruin tucked within Staten Island’s woodlands. For over a century, this farm colony offered shelter and work to the city’s impoverished, only to be left derelict by the late 1970s. Today its crumbling dormitories and overgrown fields provide a friendly yet adventurous glimpse into New York’s past, drawing enthusiasts of urban exploring in New York. The atmosphere is eerily captivating – moss-covered walls, shattered windows, and graffiti-laced hallways speak to decades of neglect and the countless lives that passed through. From its hopeful start in the 19th century to its present state as a fenced-off “ghost town,” the story of the Farm Colony is rich in history, cautionary in its decline, and thrilling for modern URBEX adventurers who wander its ruins.

In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll uncover when the Farm Colony opened and how long it operated, what daily life and activities once animated its grounds, why this unique institution was ultimately abandoned, and the historical significance that lingers. We’ll also delve into the colony’s status as an urban exploration hotspot – complete with local legends like the notorious “Cropsey” – that continues to fascinate and frighten. Join us as we journey through the rise, fall, and enduring mystery of the New York City Farm Colony, a true hidden gem of New York City’s forgotten history.

Origins of the New York Farm Colony: A 19th-Century Poor Farm

The roots of the New York City Farm Colony stretch back to the early 19th century. Long before Staten Island was a New York City borough, local officials sought a solution for caring for the poor. In 1829, the county government of Richmond County (Staten Island) purchased 96 acres of farmland from the Martineau family for $3,000 to establish a poorhouse. This facility, known as the Richmond County Poor Farm, opened that year as a place where indigent New Yorkers could receive food and shelter in exchange for their labor. It was essentially an almshouse with a farm, reflecting a common 19th-century approach to welfare: able-bodied poor residents were expected to work on the farm, growing their own sustenance and contributing to the institution’s upkeep.

In its early decades, the poor farm was modest. The first building on the site went up in the 1830s, likely a simple dormitory or farmhouse structure. Over time, more structures were added. By the late 1800s, the compound had grown into a small campus with multiple dormitories and support buildings, arranged in a bucolic setting amid cultivated fields. Staten Island’s isolation and rural character made it a fitting location for such an experiment in agrarian charity. Here, the impoverished could be kept away from the crowded slums of Manhattan and Brooklyn, and given fresh air, open space, and productive work tilling the land.

A major turning point came in 1898, when New York City’s five boroughs were consolidated into a single metropolis. Staten Island (formerly Richmond County) became one of those boroughs, and with consolidation the city assumed control of the old poor farm. The institution was reorganized and renamed the “New York City Farm Colony” in 1898, marking its official opening under city management. This change wasn’t just cosmetic – it reflected a new philosophy. City officials envisioned the Farm Colony as a self-sustaining refuge for the poor, a place where the “able-bodied indigent” could be sheltered, fed, and put to work in a humane environment. In essence, the Farm Colony was to be a utopian agricultural community for society’s downtrodden, and it was one of several such “farm colonies” emerging in the United States around that time.

A Utopian Vision: Life and Work on the New York Farm Colony

When the New York City Farm Colony truly hit its stride in the early 20th century, it embodied progressive ideals of self-sufficiency. By the 1900s, the colony’s campus spanned over 100 acres of gentle Staten Island hills and forests. About 63 acres were under active cultivation at one point, planted with fruits, vegetables, and even grains like wheat and corn to feed the residents and other city institutions. In addition to crops, residents raised livestock and maintained the farm’s operations. The work was hard but purposeful: rather than receiving charity outright, residents effectively earned their keep through their labor. Reports from the time indicate the Farm Colony’s agricultural output often exceeded its own needs – surplus produce was sold to other institutions or on the market, generating income and proving the viability of the experiment.

During its peak years in the early 1900s, the Farm Colony was bustling. By 1903, the facility had seven dormitory buildings and various staff buildings, laid out in a campus-like arrangement amid the fields. The architecture of the new buildings constructed in this era was notable: gambrel-roofed, fieldstone structures in a Dutch Colonial Revival style, blending a quaint old-world aesthetic with sturdy functionality. These are the very buildings whose ruins still stand today, their stone walls and distinctive rooflines slowly crumbling but recognizable. The tranquil setting on the edge of the Staten Island Greenbelt added to the colony’s pastoral atmosphere – it was surrounded by woodlands, with fresh country air that reformers of the day believed was beneficial to the poor and ill.

The population of the Farm Colony grew steadily in the early 20th century, indicating significant demand for its shelter. By the first decade of the 1900s, the colony housed over 800 residents and employed about 150 staff members to manage the facility. Most residents were adult men and women who were homeless, elderly, or unable to support themselves financially. They were often referred to as “inmates” in the terminology of the time (not implying criminality, but simply denoting residents of an institution). Life at the Farm Colony revolved around routine and work: those who were physically able spent their days planting, harvesting, tending to animals, preparing meals, and doing maintenance tasks. In return, they received room, board, and basic medical care. Descriptions paint a picture of a community that, at its best, functioned like a large communal farm with a humanitarian mission – a far cry from the grim urban almshouses or workhouses many residents might have otherwise faced.

There was even interplay with the adjacent Seaview Hospital, located just across Brielle Avenue. Seaview was established in the early 20th century (circa 1913) specifically as a tuberculosis sanatorium and hospital. In 1915, the administration of the Farm Colony was formally merged with Seaview Hospital’s. This administrative link meant some shared resources and oversight between the poor farm and the medical facilities. The farm colony’s fresh produce likely helped feed patients at Seaview, and in later years some Farm Colony residents who became infirm might be transferred to Seaview’s care. Even today, the two sites are historically entwined – they together form the Farm Colony–Seaview Hospital Historic District, which was designated a New York City landmark in 1985. This joint landmark status recognizes the unique concentration of early 20th-century institutional architecture in the area and the important social history of both sites.

Heyday and Decline: From Crowded Fields to Empty Halls

At its height in the 1920s and 1930s, the New York City Farm Colony was home to a substantial population of indigent New Yorkers. The Great Depression era in particular saw a surge in residents: nearly 1,500 people were housed and fed at the Farm Colony during the Depression years. By 1936, records show approximately 1,428 residents living at the colony, most of them elderly or individuals with disabilities who had nowhere else to go. The expansion of buildings continued to accommodate this growth – new dormitories and facilities were added through the 1930s, creating, in essence, a self-contained village of the poor on Staten Island.

However, the seeds of the Farm Colony’s decline were sown by mid-century. Changes in social policy and the evolution of public welfare gradually made institutions like this seem outdated. A significant shift occurred in 1924, when New York City placed the Farm Colony under the jurisdiction of its Homes for Dependents agency. With this change came a more benevolent policy: the longstanding requirement that all residents work on the farm was lifted in 1924. This reflected a changing attitude toward the elderly and infirm poor – recognizing that many residents were not actually “able-bodied” and should not be compelled to labor. After 1924, those who could work still did, but the Farm Colony increasingly functioned as more of an old-age home or poor seniors’ residence rather than a strict work farm.

By the 1930s, indeed, a large proportion of the colony’s residents were elderly men and women without family or income. They lived in the dormitories, took their meals in communal dining halls, and spent their days in light activities if they were able – tending small garden plots, sewing, or simply socializing on the porches. Photographs and accounts from this time describe rows of white-haired residents sitting outside the stone buildings on warm days, or shuffling through the colony’s paths amid the trees. The colony had effectively become a geriatric poorhouse as younger able-bodied indigents found other opportunities or were served by different programs.

The final blow to the Farm Colony’s original mission came with the introduction of federal social safety nets. The Social Security Act of 1935 provided many elderly Americans with a small income in old age, reducing the necessity of entering poorhouses for survival. Decades later, in the 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs – such as Medicare, Medicaid, and improved welfare benefits – further ensured that destitute seniors and the poor could get support without resorting to institutionalization. As these programs took effect, the population of the Farm Colony sharply declined. No longer were there thousands of indigent people who needed to trade labor for shelter on a farm; many could now afford basic lodging or were taken in by modern nursing homes.

By the late 1960s, the Farm Colony was largely a relic in a changing world. Its remaining residents were transferred out gradually to other facilities, including the Sea View nursing home across the road (the modern successor of Seaview Hospital). In 1975, New York City officially closed the Farm Colony for good, ending its nearly 146-year run (counting from the 1829 poor farm origins) or 77-year run under the “Farm Colony” name. The closure marked the end of an era – the Farm Colony was one of the last functioning poor farms in the United States. Its demise was a direct result of progress in social welfare: as one historian quipped, “the Social Security system did what decades of reforms could not, emptying the poorhouse”.

When the doors closed in 1975, the once-hopeful farm colony was left to an uncertain fate. The buildings were boarded up, the fields went fallow, and an extraordinary silence fell over the place. A New York Times article described the site a decade later as “a jungle in there”, already overrun by vegetation and disrepair. But the story was far from over – the Farm Colony’s afterlife as an abandoned site would prove as eventful, in its own eerie way, as its years of operation.

Abandonment and Decay: Decades of Neglect

After its closure, the New York City Farm Colony quickly slipped into decay. For city officials, the 25 handsome but now empty buildings on 96 acres of land were both a problem and an opportunity. Initially, New York City hoped to dispose of the property. In 1980, the city attempted to sell the entire Farm Colony grounds to private developers, reasoning that such a large tract of land in Staten Island could be put to new use. However, this plan immediately met resistance. Local environmentalists and many Staten Island residents objected to potentially losing the green open space and historic structures to generic development. The Farm Colony sat adjacent to the Staten Island Greenbelt (a network of parks and natural areas), and neighbors wanted it preserved or at least responsibly reused.

Bowing to community pressure, the city stopped the sale. Instead, in 1982, the Department of General Services transferred about 25 acres of the Farm Colony land to the NYC Parks Department, which promptly annexed that portion into the Greenbelt park system. These 25 acres were largely open fields and woods on the edges of the property – meaning they would remain undeveloped public land. The remaining 70+ acres, including all the main buildings, stayed under city ownership but gained protection: in 1985, New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the Farm Colony (together with the Seaview Hospital complex across the street) as an official city historic district. The designation recognized the site’s significance as a rare surviving poorhouse/farm colony and ensured that the distinctive fieldstone dormitories could not be demolished without special approval.

Despite the landmark status, little was done to actually maintain or restore the structures. With no active use, the buildings succumbed to nature and vandalism. Roofs began to leak and collapse, ivy and weeds crawled over brick and stone, and interiors were stripped by looters or wrecked by the elements. A sense of forsakenness grew year by year. The once neatly tended farm fields turned to woodland and thicket, erasing roads and pathways under tangles of green. By the 1990s, the site had the appearance of a lost village being reclaimed by the forest.

A few minor uses did carve out pieces of the property. In 1993, a local youth baseball league built a Babe Ruth League baseball field on one corner of the Farm Colony land, and another field was added in 2001. These ballfields occupied former farm meadows and reduced the overall “abandoned” footprint somewhat (the entire site is now about 43 acres, down from the original 96). Additionally, one of the historic buildings was repurposed as a Parks Department recreation center – notably the old kitchen and dining hall building was restored and now functions as the Greenbelt Recreation Center. However, beyond these small incursions, the majority of the Farm Colony has remained eerily idle and fenced-off.

Over the decades, various redevelopment proposals sputtered to life, only to stall out. At times, city administrations and private developers eyed the crumbling colony and saw potential for new housing or community facilities. One ambitious plan, conceived around 2013, was known as “Landmark Colony.” The idea was to adaptively reuse some of the historic structures and build new senior housing on the site – giving the property a second life serving Staten Island’s aging population. In fact, the City Council approved a redevelopment plan in 2016 for a $91 million project including 344 units of senior housing, projected for completion by 2018. The plan even called for preserving a few of the picturesque ruins as “arrested ruins” – stabilized relics as a nod to the history within the new development.

However, as of the mid-2020s, the grand redevelopment has yet to materialize. The private developer (NFC Associates) struggled with land-use approvals and financing, and the project was put on indefinite hold by 2017. The City never finalized the transfer of the property, and the once-bold vision quietly fizzled. In August 2022, local news reported that the senior housing dream “might be dead” – the site remained in limbo with no progress and no clear path forward. The city still technically owns the property, and officials have voiced openness to new ideas, but tangible action has been elusive. For now, the Farm Colony’s fate is to remain as it has for 50 years: a stark tableau of abandonment.

Walking through the site today (for those who manage to slip inside), one can see firsthand the decaying structures that earned the colony its landmarked status. The once grand dormitories stand roofless and hollowed out. Many feature thick fieldstone walls and gambrel roofs that harken back to early American farmhouses – now partially collapsed or sagging from decades of water damage. Inside, what’s left of plaster walls and wooden beams are covered in graffiti and moss. Trees and vines sprout from upper floors where roofs have caved in, literally nature overtaking architecture. In some buildings, rusted bed frames or peeling paint hint at their past life as a bustling institution; in others, debris and fallen plaster make it hard to imagine humans ever lived there. Silence dominates, broken only by the rustle of leaves or perhaps the clink of a spray paint can in the distance.

City officials periodically clear overgrowth or seal up breaches in the fencing, but the sheer scale of the site makes it hard to secure fully. By the 2000s and 2010s, the Farm Colony had become known as a local eyesore and trouble spot – its forlorn buildings attracting vandals, partiers, and criminal mischief after dark. Despite “No Trespassing” signs, the lure of the historic ruins proves irresistible to many.

Urban Exploration and Legends at the New York Farm Colony

Ironically, the very neglect that officials bemoan has made the New York City Farm Colony a kind of mecca for urban explorers and thrill-seekers. Among urban exploring in New York circles, the Staten Island Farm Colony is legendary – a massive abandoned complex hidden in plain sight within city limits. It offers that perfect cocktail of qualities urban explorers love: relative seclusion, a rich history to discover, and a dash of danger (both physical and legal). Indeed, as early as the 2000s, the spot was popular with young urban explorers, who snuck in to take photos or simply experience the eerie atmosphere. Local teens even co-opted the space for recreational use; for years, paintball enthusiasts held weekend skirmishes in the Colony’s woods and empty buildings, leaving behind gelatin shell casings and splatters of colored dye on top of the layers of graffiti.

Entering the Farm Colony remains officially off-limits, but that hasn’t stopped intrepid visitors. The property is encircled by a chain-link fence, yet gaining access is notoriously easy – there are often gaps or holes cut in the fence that beckon the curious. For instance, near an old bus stop on Brielle Avenue, one can find a wide-open section of fence that has effectively become an unofficial entrance, as noted in a 2022 report. Once inside, a network of overgrown paths and old roads leads you from one collapsing building to the next. Explorers tread carefully, knowing that some floors are unsafe and staircases may give way. The air is tinged with moisture and the scent of earth and decay. Nature has made itself at home here: you’ll find saplings growing in former day rooms, birds nesting in rafters, and the occasional deer wandering through, unperturbed by the skeletons of human habitation.

For those drawn to the macabre, the Farm Colony does not disappoint. Over the years, it has accumulated dark legends and ghost stories that only amplify its reputation. Some of these tales date back nearly a century. In the 1920s, a local story goes, a young boy went missing in the woods near the Farm Colony and Seaview Hospital. Allegedly, he was last seen walking with an elderly man who was a Farm Colony resident, and then he vanished. The boy was never found, and whispers of foul play haunted the community – an ominous hint that not all was pastoral perfection on the colony’s grounds. Though hard evidence was lacking, this incident planted seeds of an enduring association between the Farm Colony and unsolved mysteries.

Far more notorious are the events of the 1970s and 1980s, when the Staten Island Farm Colony gained infamy as part of the “Cropsey” urban legend. During those years, a number of children on Staten Island disappeared under disturbing circumstances, and the abandoned Farm Colony (along with the closed Willowbrook State School nearby) was thrust into the spotlight. The most tragic case was in 1987, when 12-year-old Jennifer Schweiger, a girl with Down syndrome, went missing and was later found buried in a shallow grave in the woods on the colony’s outskirts. The discovery of her body on the Farm Colony’s property sent shockwaves through the city. It turned out that a man named Andre Rand, a drifter and former custodian at Willowbrook, had been living illicitly in the area’s woods and tunnels. Rand was arrested and ultimately convicted of kidnapping (though not murder, as no one witnessed the killings) in connection to Jennifer’s death and another girl’s disappearance. He is suspected in several other child disappearances as well. Rand’s crimes and lurid rumors about his activities (some said he prowled the abandoned buildings or conducted satanic rituals) became intertwined with the legend of “Cropsey,” a boogeyman figure that had been part of Staten Island campfire lore for years.

The 2009 documentary film “Cropsey” explored these events, interviewing locals and even venturing into the Farm Colony ruins in search of clues to the alleged satanic cults and the legacy of Andre Rand. The film helped cement the Farm Colony’s chilling reputation. To this day, some refer to the entire swath of woods, ruins, and tunnels in this part of Staten Island as “Cropsey’s playground,” an area haunted by both very real tragedies and ghostly tales. Macabre rumors continue to cling to the Farm Colony: visitors have reported finding animal bones arranged in strange patterns, hearing whispers or childlike cries in the empty buildings, or seeing flickering lights deep in the tunnels at night – signs, they say, of lingering dark rituals or restless spirits. While many of these claims are likely exaggerations fueled by imagination, they contribute to the site’s aura. As one writer put it, the whole area feels “occupied by ghosts…haunted by the real memories of gross mistreatment” and tragedy that unfolded there and at Willowbrook.

Even without supernatural embellishment, the Farm Colony can send shivers down one’s spine. Nighttime explorers have described the experience as genuinely frightening: the crunch of leaves underfoot echoing in the silent courtyard, the sight of a ragged curtain suddenly fluttering in a shattered window, or the way a tree’s shadow can look uncannily like a human figure standing in a dark hallway. It doesn’t help that local folklore insists some of the old residents never truly left – there are anecdotes of people seeing an “old man in a hospital gown” wandering among the trees or a “lady in white” peering from an upper floor window of the dormitory, only to vanish when approached. Whether one believes in ghosts or not, it’s easy to imagine shapes in the gloom when walking through the Colony on a dusky afternoon. In fact, after the colony closed, some former patients (residents) of the institution – now homeless or mentally ill – were said to still wander the grounds in the early years of abandonment, having nowhere else to go. These living figures perhaps gave rise to the ghost stories, appearing as silent, ragged wanderers amid the ruins, blurring the line between reality and the paranormal.

Despite the dangers and the legends, the Farm Colony’s draw for urban explorers (URBEX enthusiasts) remains strong. It offers a rare slice of forbidden New York City history that one can physically step into. Explorers come with cameras to document the beautiful decay – the way tree roots snake over a cracked tile floor, or how decades-old graffiti mixes with 1930s WPA murals peeling off a wall (indeed, in the 1930s artists painted murals in some buildings as part of Federal Art Project efforts). Photographers relish the moody, post-apocalyptic scenery, especially on misty mornings or under dramatic late-day light. History buffs, meanwhile, walk the site envisioning the former life here: the laughter of residents on a summer day long ago, or the rows of vegetables once neatly planted in what’s now secondary forest.

Local officials have warned trespassers to stay away – the NYPD occasionally patrols or responds to calls at the site, and there’s always a risk of arrest for defiant explorers. But enforcement is sporadic, and the temptation is high. One comment on a Staten Island forum joked that the Farm Colony is basically an “accidental museum” – not formally open, but effectively accessible to anyone willing to bypass a fence, offering a raw exhibit of New York’s past, free of charge (and oversight). Thrill seekers from across the city have included the Farm Colony on their bucket lists of abandoned places to visit, alongside spots like North Brother Island or the Freedom Tunnel. It’s even been featured on lists of “New York City’s most accessible ruins” for urban adventurers. Just remember, those who enter do so at their own risk – both physically, as structures could collapse, and legally.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Beyond the graffiti and ghost stories, the New York City Farm Colony holds a significant place in the broader history of New York and how society cares for its vulnerable. In its century-plus of operation, thousands of people lived and died here – people who, absent the Farm Colony, might have had no shelter at all. It was part of a larger poorhouse system that once spanned America, a system that is now virtually extinct. The Farm Colony’s abandonment itself tells a story: it marks the transition from the old poor farm model to modern welfare programs. The closure in 1975 symbolized how federal initiatives like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid rendered these antiquated institutions obsolete. Studying the Farm Colony’s history offers insight into how attitudes towards poverty, aging, and social responsibility evolved over time.

The site also carries architectural and cultural significance. Its remaining structures, though in ruins, are enduring examples of early 20th-century municipal architecture with a purpose. The use of fieldstone and Dutch Colonial Revival design gives the colony a timeless, rustic appearance – one reason the Landmarks Commission moved to protect it. In 1985, when the Farm Colony and Seaview were landmarked, the intention was to perhaps spur rehabilitation by recognizing their importance. While that rehabilitation largely didn’t happen, the designation did ensure that the story isn’t forgotten. Walking through today, one can still identify the old dormitories, the dining hall, the laundry building, and other structures, each with interpretive value for those interested in the past. Even in decay, the “bones” of the place speak volumes: from the layout of the colony (buildings arranged around courtyards, linked by old roadways) we see how a self-contained charitable community was organized in 1900. The remnants of orchards or flower beds hint at the therapeutic intent of farm labor. There’s even a small potter’s field cemetery nearby where some residents were buried, underscoring that this was a whole life community for many, from arrival to death.

The Farm Colony’s story is also intertwined with that of Staten Island itself – often dubbed NYC’s “forgotten borough.” Staten Island has long been a place where the city’s inconvenient or unsightly elements were placed (from landfills to facilities like Willowbrook). The Farm Colony was one such element: a safe remove for housing the poor. Yet today, Staten Islanders are among the site’s fiercest protectors, acknowledging it as part of their local heritage. Efforts to reuse it have aimed to balance preservation and progress for the community. Although the future remains uncertain, there’s a lingering hope that any new development will honor the Farm Colony’s history – perhaps by incorporating the surviving buildings as community space or a museum where the tale of the poor farm can be told to new generations.

For now, the New York City Farm Colony stands quietly as a ruined monument to a vanished way of life. It’s a place where, for those who know its history, every crumbling wall and rusted bed frame seems to whisper stories: of hard labor under the summer sun, of simple pleasures like harvest dances or holiday meals among those who had little, of the sorrow of abandonment when society moved on, and yes, of the strange afterlife where vandals and legend-trippers dance around bonfires in the night. Few sites in New York encapsulate such a breadth of time and emotion.

Conclusion

From its opening year in 1898 as a progressive haven for the poor, to 77 years of operation before shutting its doors, the New York City Farm Colony has traveled the full arc from hope to neglect. Its activities – farming, caregiving, community living – once provided salvation for the needy, while its abandonment has provided fascination for urban explorers. The reasons for its downfall are rooted in positive change (improved social programs) even as the abandoned result is poignantly negative (a wasteland of wasted architecture). Yet, the very historical significance of this place ensures it’s not truly forgotten. As an urban exploring (URBEX) destination, the Farm Colony today educates and awes in a way no textbook ever could, offering a tangible encounter with history’s footprint.

Whether one is drawn by the thrill of exploration, the weight of the past, or the eeriness of legend, the Farm Colony leaves a lasting impression. It stands among the notable places abandoned in New York – not just for its grand decay, but for what it represents about compassion and change in New York City. Perhaps in the coming years, the colony will finally be reborn in a new form, but until then it remains a silent, powerful reminder: sometimes the most adventurous journeys are into the forgotten chapters of our own backyards.

Regardless of what the future holds, the New York City Farm Colony’s legacy endures – part cautionary tale, part inspiration. It urges us to remember those who came before, to preserve stories even as structures crumble, and to find beauty and meaning even in ruins. For urban explorers with a sense of history, few experiences can top stepping through the gates of the Farm Colony, where the past and present coexist in dilapidated harmony, waiting to be discovered anew.

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in learning about the Hotel Polissya in Ukraine, the Dunnellon Ranger Station in Florida or the Concrete City in Pennsylvania.

A 360-degree panoramic photograph captured inside the abandoned New York Farm Colony on Staten Island, New York. Photos by: Black Paw Photo

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.