The Howell Building at Central State Hospital: Exploring a Forgotten Relic of Georgia’s Mental Health History

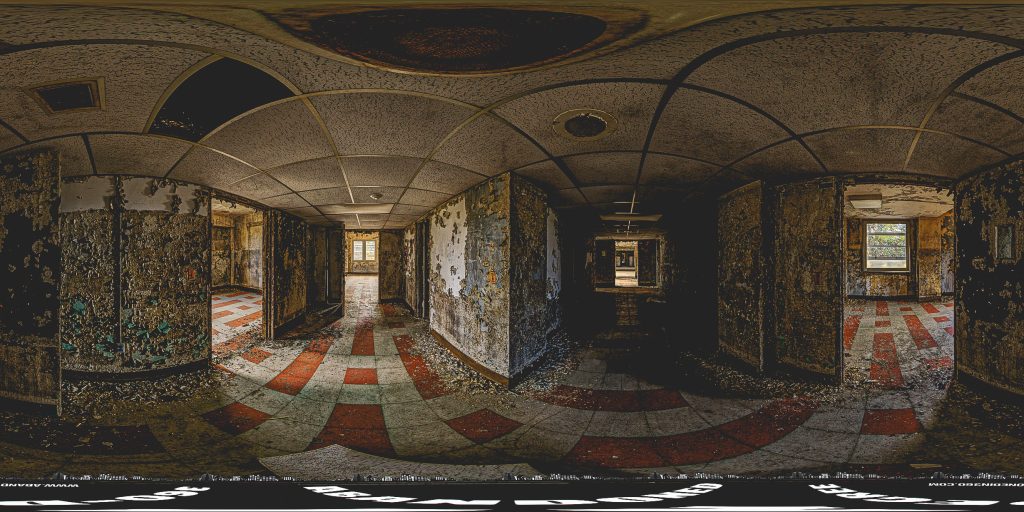

Step inside the abandoned Howell Building at Central State Hospital in Milledgeville, Georgia, where peeling paint, silent corridors, and fading history create the perfect atmosphere for urban explorers. This forgotten structure offers a rare glimpse into the past, inviting you to study every detail of its decay from a safe distance.

Scroll down to experience the amazing 11-panoramic image 360-degree virtual tour below, carefully captured to showcase the Howell Building at Central State Hospital from multiple perspectives. Move through the space virtually as if you were there in person, exploring every angle of this hauntingly beautiful relic.

Click here to view it in fullscreen.

When you’re searching for the ultimate URBEX adventure in Georgia, few locations carry the weight of history quite like the Howell Building in Milledgeville. This crumbling structure stands as a haunting reminder of an era when mental health treatment looked drastically different from what we know today. For those passionate about urban exploring in Georgia, the Howell Building offers a glimpse into the troubled past of what was once the world’s largest mental institution.

A Foundation Built on Reform

To understand the Howell Building, you first need to understand its birthplace: Central State Hospital. In the 1830s, a wave of social reform swept across America, calling for humane treatment of the mentally ill rather than imprisonment or abandonment. Georgia answered this call in 1837 when the state legislature passed a bill creating the “State Lunatic, Idiot, and Epileptic Asylum” in Milledgeville, the state capital at the time.

The institution opened its doors in December 1842, welcoming its first patient in tragic circumstances. Tilman Barnett, a 30-year-old farmer from Bibb County, arrived chained to a horse-drawn wagon, described as violent and destructive. Within six months, Barnett died of what doctors termed “maniacal exhaustion,” becoming the facility’s first casualty in what would be a long and dark history.

What started as a noble effort to provide care gradually transformed into something far more sinister. By the mid-20th century, the institution had grown into a massive complex spanning over 2,000 acres with approximately 200 buildings. It was during this explosive growth period that the Howell Building came into existence.

The Birth of the Howell Building at Central State Hospital

The Howell Building was constructed in 1939, with its cornerstone marking that pivotal year, though the building was officially commissioned in 1940. This made it one of the newer additions to the sprawling Central State Hospital campus in Milledgeville, arriving during a period when the institution was rapidly expanding to accommodate Georgia’s growing population of psychiatric patients.

The building rose along what is now Mobley Road, joining dozens of other structures that housed thousands of patients deemed unfit for society. Unlike the historic Powell Building from 1842 or the imposing Jones Building from 1929, the Howell Building represented the hospital’s continued expansion during an era when institutionalization was seen as the primary solution for mental health treatment.

For those interested in abandoned places in Georgia, the Howell Building stands out because of its relatively short operational life. Despite being one of the newest structures on campus, it operated for only 30 to 35 years before falling into disuse in the early 1970s. This brief operational period tells us something important about the dramatic shift in mental health care that occurred during the mid-20th century.

Life Inside Central State Hospital

To appreciate what the Howell Building witnessed during its active years, you need to understand daily life at Central State Hospital during the 1940s through 1970s. By the 1960s, the hospital had grown into the largest mental health facility in the world, competing only with New York’s Pilgrim State Hospital for that dubious distinction.

The hospital population swelled to nearly 12,000 patients by the 1960s, creating conditions that were overcrowded, understaffed, and ultimately dangerous. The doctor-to-patient ratio reached a shocking 1 to 100, making proper care virtually impossible.

Patients at Central State Hospital endured treatments that ranged from outdated to outright barbaric. Doctors employed lobotomies, insulin shock therapy, and early electroshock treatment, alongside less sophisticated methods. Children were confined to metal cages, while adults faced forced steam baths, cold showers, straitjackets, and other harsh treatments.

The Howell Building, operating during this peak period, would have housed dozens of patients living under these conditions. Its halls echoed with the sounds of suffering, confusion, and the institutional routine that defined life for thousands of forgotten Georgians. Many patients arrived for minor issues or conditions that today wouldn’t warrant institutionalization at all, yet they spent years or even decades locked away from society.

The Scandal That Shook Georgia

The true horrors occurring within Central State Hospital, including facilities like the Howell Building, remained largely hidden from public view until 1959. That year changed everything for the institution and indirectly contributed to the eventual abandonment of buildings like the Howell Building.

Journalist Jack Nelson of The Atlanta Constitution exposed widespread abuses at the hospital, earning the Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting in 1960. Nelson’s investigation revealed shocking conditions that stunned the state and nation.

Nelson discovered that the hospital employed not a single psychiatrist among its doctors, and one-fourth of the medical staff had histories of alcoholism or drug abuse. Even more disturbing, some physicians had been hired directly from the hospital’s own patient wards—the inmates were quite literally helping to run the asylum.

The exposé revealed that a nurse performed major surgery without doctor supervision and that a physician, moonlighting for a pharmaceutical company, used experimental drugs on patients without their consent. These weren’t isolated incidents but symptoms of systematic neglect and abuse that had flourished for decades.

The scandal sent shockwaves through Georgia. Hospital staff were fired, and the state finally began providing additional funding that superintendents had begged for years earlier. But the damage to Central State Hospital’s reputation was irreversible. Parents across the South had long threatened misbehaving children with being “sent to Milledgeville,” and now the public understood why that threat carried such terror.

The Forgotten Dead

One of the most disturbing aspects of Central State Hospital’s history—and by extension, the Howell Building’s legacy—involves the treatment of deceased patients. Because so many patients lived at the hospital for years, often forgotten or shunned by their families, the hospital operated its own mortuary and employed carpenters whose sole job was building caskets.

For more than a century, the hospital buried its dead beneath small metal stakes, each emblazoned with a number corresponding to a patient’s file—no names, no dates of birth or death, no symbols of lives outside the hospital. This dehumanizing practice reduced human beings to numerical data points, erasing their identities even in death.

The situation grew worse in the late 1960s, around the time the Howell Building was approaching its final years of operation. Grounds keepers, who were patients themselves, found the grave markers a nuisance when mowing the cemeteries, so they simply pulled stakes from the ground—at least 10,000 of them—and tossed them into the woods. These graves, containing more than 25,000 individuals, became forever anonymous.

For URBEX enthusiasts exploring the area today, the cemeteries scattered across the Central State Hospital campus serve as sobering reminders of the thousands who lived and died within these walls, including those who may have spent time in the Howell Building during its operational years.

The Era of Deinstitutionalization

The forces that led to the Howell Building’s abandonment in the early 1970s were set in motion by multiple factors converging simultaneously. Following Jack Nelson’s explosive 1959 exposé, public pressure mounted for reform. At the same time, the pharmaceutical industry was developing new medications that offered hope for treating mental illness outside institutional settings.

By the mid-1960s, as new psychiatric drugs allowed patients to move to less restrictive settings, Central State’s population began its steady decline. A decade before the national movement toward deinstitutionalization, Georgia governors Carl Sanders and Jimmy Carter began emptying Central State in earnest, sending mental patients to regional hospitals and community clinics, and people with developmental disabilities to small group homes.

This shift in mental health care philosophy fundamentally changed the role of massive institutions like Central State Hospital. Rather than warehousing thousands of patients in large facilities, the new approach emphasized community-based care and outpatient treatment. As patient numbers declined, buildings became unnecessary and expensive to maintain.

The Howell Building, having opened in 1940, served for approximately three decades before the deinstitutionalization movement rendered it obsolete. By the early 1970s, the building fell into disuse, becoming one of the first casualties of this massive shift in mental health policy. While the hospital’s older, more iconic structures like the Powell Building (1842) and Jones Building (1929) received attention, the relatively modern Howell Building was simply abandoned and left to decay.

What Remains Today of the Howell Building at Central State Hospital

For those interested in urban exploring in Georgia, the Howell Building presents a fascinating but sobering destination. By the time photographers began documenting the structure, it exhibited significant vine growth, broken windows, and general decay, with portions of the roof having started to collapse.

The building’s cornerstone, still visible, bears the date 1939—a tangible connection to the era when institutionalization represented the primary approach to mental health care in America. Walking the grounds around the Howell Building, you can sense the weight of history pressing down. This isn’t just another abandoned structure; it’s a monument to changing attitudes about mental illness, the failures of institutional care, and the thousands of lives that passed through these halls.

Several of the beautiful brick buildings on the “quad” surrounding a lush pecan grove have been boarded up since the late 1970s and have begun to decay into haunted ruins. The Howell Building sits among these decaying structures, slowly being reclaimed by nature. Vines crawl up brick walls, windows gape empty like hollow eyes, and vegetation pushes through cracked pavement and crumbling foundations.

Inside, evidence of the building’s former life remains. Fixtures, institutional furniture, and the bones of the structure itself tell stories of the patients and staff who once filled these rooms. The layout reveals the institutional nature of the facility—long corridors, small rooms, and features designed for observation and control rather than comfort or healing.

The Broader Central State Hospital Complex

The Howell Building doesn’t exist in isolation. It’s part of the larger Central State Hospital campus, which remains one of the most significant collections of abandoned institutional buildings in the southeastern United States. For URBEX enthusiasts, the entire campus represents a treasure trove of exploration opportunities, though it’s important to note that many buildings are structurally unsound and access is restricted.

The iconic Powell Building, constructed in 1842, remains the oldest standing structure on the hospital grounds. Unlike the Howell Building, this historic structure has received more attention for preservation efforts. The massive Jones Building, erected in 1929, once served as a general hospital offering medical care to patients and area residents. Today, it stands as a decaying giant with pine saplings sprouting from its red-tile roof.

As the asylum’s buildings were vacated, four were converted into prisons, with one prison remaining on the property today. A separate facility, the Cook Building, houses 179 forensic patients who have been found not guilty by reason of insanity or incompetent to stand trial.

The contrast between the abandoned buildings like the Howell Building and the still-operational facilities creates a surreal landscape. Modern security exists alongside crumbling ruins, and the echoes of the past mingle with present-day operations. This juxtaposition makes the Central State Hospital campus unique among abandoned places in Georgia.

Urban Exploration Considerations

For those planning to explore abandoned sites in Georgia, the Howell Building and broader Central State Hospital campus require special consideration. While the site holds tremendous historical and photographic appeal, several important factors must be kept in mind.

First, much of the property remains under active security patrol. The operational portions of Central State Hospital continue to serve forensic psychiatric patients, meaning security presence is substantial and consistent. Trespassing can result in serious legal consequences, including arrest and prosecution.

Second, the abandoned buildings present significant safety hazards. Decades of neglect have weakened structures, creating risks from collapsing floors, falling debris, unstable roofing, and hazardous materials like asbestos. The Howell Building itself shows evidence of roof collapse and structural deterioration that makes entry extremely dangerous.

Third, the site deserves respect as a place where real suffering occurred. Thousands of people lived, were treated (often poorly), and died on this campus. Urban exploration should be conducted with awareness of this history and the dignity owed to those whose lives intersected with these buildings.

Fortunately, legitimate opportunities exist to experience the Central State Hospital campus legally and safely. The Milledgeville Convention and Visitors Bureau offers trolley tours led by former hospital employees, providing historical context and access to portions of the grounds. These tours allow visitors to learn about buildings like the Howell Building while respecting property boundaries and safety concerns.

The Cultural Impact

The story of Central State Hospital and structures like the Howell Building extends beyond the immediate area, influencing Southern culture and literature in profound ways. Famous author Flannery O’Connor lived just seven miles from the asylum and its influence permeates her work. The hospital’s presence shaped the community’s identity for generations, serving as the county’s largest employer while simultaneously carrying a stigma that affected countless families.

Scholar Mab Segrest notes that Central State “impacted kinship networks all across the state, and many Georgians still carry painful shards of this history”. The hospital became a threat used by parents throughout the South to control children’s behavior, a catchphrase that embodied society’s fear and misunderstanding of mental illness.

For modern urban explorers interested in abandoned places in Georgia, sites like the Howell Building offer more than aesthetic decay and photographic opportunities. They provide connections to this complex cultural history, serving as physical reminders of how society has treated its most vulnerable members and how far mental health care has evolved—while also highlighting how far we still need to go.

Preservation Efforts and Future Uncertainty

The fate of the Howell Building and similar structures on the Central State Hospital campus remains uncertain. While some historic buildings have received attention for preservation, many others—including the Howell Building—continue deteriorating without intervention. The cost of maintaining or restoring these structures is substantial, and the painful history they represent makes preservation decisions complex.

Some buildings on campus have faced demolition. The state of Georgia periodically evaluates which structures to preserve, repurpose, or demolish based on structural condition, historical significance, and practical considerations. The Howell Building’s relatively short operational life and lack of architectural distinction compared to older structures makes its long-term preservation unlikely.

A small museum operates in an old railroad depot on the campus quad, working to preserve and share the hospital’s history. Volunteers and historians have documented the site through photographs, oral histories, and research, ensuring that even if buildings like the Howell Building eventually disappear, their stories will survive.

For the URBEX community, this uncertainty adds urgency to documentation efforts. Photographs and videos captured today may become the only records of these structures as they existed before final collapse or demolition. Each visit to abandoned buildings in Georgia, including the Howell Building, becomes an act of historical preservation, freezing a moment in the ongoing process of decay and transformation.

Lessons from the Howell Building at Central State Hospital

What can we learn from a building that operated for barely three decades before abandonment? The Howell Building’s story encapsulates the rapid evolution of mental health treatment in America and the consequences of institutional approaches to care.

Built during an era when “bigger is better” guided mental health policy, the Howell Building represented confidence in the institutional model. Its construction in 1939 came during a period of expansion at Central State Hospital, when planners believed the solution to mental illness lay in large facilities where patients could be concentrated and treated en masse.

Yet within 30 years, that entire philosophy had been discredited and dismantled. The building that once housed vulnerable patients seeking help became a vacant shell, abandoned as quickly as the treatment philosophy that created it. This rapid obsolescence reflects how dramatically our understanding of mental health and appropriate care has evolved.

The building also reminds us of the human cost of failed systems. Every window in the Howell Building looked out on lives interrupted, families separated, and individuals warehoused rather than healed. The numbered graves scattered across the campus belong to people who entered seeking help but found only confinement and, too often, death.

The Psychology of Abandonment

There’s something particularly haunting about abandoned mental health facilities, and the Howell Building is no exception. Unlike abandoned factories or schools, structures that once housed psychiatric patients carry an additional psychological weight. They remind us of society’s changing attitudes toward mental illness and our complicated relationship with those experiencing psychological distress.

Urban exploring in Georgia offers numerous abandoned sites, but few carry the emotional complexity of places like the Howell Building. Walking through these spaces, even externally, evokes reflection on how we define normalcy, who decides when someone needs institutional care, and what obligations we have to our most vulnerable community members.

The building’s decay mirrors the deterioration of the institutional care model itself. As vines overtake brick walls and roots break through foundations, nature reclaims what was once a human-constructed attempt to manage and control mental illness. There’s poetry in this reclamation—the building returning to wildness just as modern care approaches recognize the importance of community integration over institutional isolation.

Connected to Larger Movements

The Howell Building’s story connects to broader historical movements that transformed American society during the mid-20th century. The deinstitutionalization movement that led to its abandonment was part of a larger civil rights awakening that questioned institutional power and advocated for individual liberty and dignity.

The same decades that saw Central State Hospital’s population decline witnessed the civil rights movement, women’s liberation, and emerging disability rights activism. These movements shared common themes: questioning authority, demanding dignity and self-determination, and pushing back against systems that segregated and controlled marginalized groups.

For patients at Central State Hospital, including those who lived in the Howell Building, deinstitutionalization represented liberation from institutions that often caused more harm than healing. Yet it also created new challenges, as community-based services struggled to meet needs previously handled (however poorly) by hospitals. This incomplete transition explains why mental health care remains a pressing issue today, with many individuals cycling through jails and homeless shelters rather than receiving appropriate treatment.

Why the Howell Building Matters for URBEX

For urban explorers passionate about abandoned places in Georgia, the Howell Building offers unique value beyond its physical presence. It represents a specific historical moment—the peak and decline of institutional mental health care in the South. While older buildings like the Powell Building showcase 19th-century institutional architecture, and modern facilities reflect current approaches, the Howell Building captures the mid-20th century institutional model at its height and fall.

The building’s relatively short operational life makes it especially interesting. Unlike structures that evolved over many decades, serving multiple purposes and undergoing numerous modifications, the Howell Building served a single purpose during a specific era before becoming obsolete. This focused history creates a time capsule effect, where the structure represents a particular moment in mental health treatment history without the layers of adaptation and reuse that complicate interpretation of longer-lived buildings.

For photographers and videographers interested in URBEX documentation, the Howell Building presents compelling visual opportunities. The contrast between its relatively modern construction (1939 versus 1842 for the Powell Building) and advanced decay creates unique aesthetic possibilities. Structural elements reveal mid-20th-century institutional design while nature’s reclamation adds texture and symbolism to images.

The Broader Georgia URBEX Landscape

While the Howell Building stands as a significant destination for urban exploring in Georgia, it exists within a rich landscape of abandoned sites across the state. Georgia’s history—from antebellum plantations to 20th-century industry—has left numerous structures ripe for exploration and documentation.

Central State Hospital campus alone offers multiple buildings spanning different eras and architectural styles. The Powell Building’s Greek Revival architecture contrasts sharply with the Howell Building’s more utilitarian mid-20th-century design. The massive Jones Building, with its collapsing interior and vegetation-covered roof, presents different exploration opportunities and challenges.

Beyond Milledgeville, Georgia hosts abandoned textile mills, shuttered schools, vacant hospitals, forgotten amusement parks, and countless other sites drawing urban explorers. What makes locations like the Howell Building particularly significant is the depth of documented history available. While many abandoned sites require speculation about their past uses and significance, Central State Hospital’s well-documented—if often troubling—history provides context that enriches exploration and documentation.

Respecting the Past While Exploring

A central tension in urban exploration involves balancing curiosity and documentation with respect for sites’ histories and the people connected to them. This tension becomes especially acute at places like the Howell Building, where real human suffering occurred and memories remain raw for affected families.

Responsible URBEX practice at locations like Central State Hospital means recognizing that these aren’t just abandoned buildings—they’re monuments to real lives, real pain, and real history. Thousands of people lived in buildings like the Howell Building, many against their will, most receiving inadequate or harmful treatment. Some died there, buried in unmarked graves that dot the campus.

Approaching these sites requires more than curiosity about decay and aesthetics. It demands engagement with difficult history, acknowledgment of past wrongs, and respect for those whose lives intersected with these structures. Photography and documentation should honor this history rather than simply exploiting it for dramatic effect.

This doesn’t mean avoiding sites like the Howell Building or refraining from URBEX exploration of abandoned mental health facilities. Rather, it means conducting exploration thoughtfully, learning the history, sharing knowledge responsibly, and maintaining awareness that our fascination with abandonment and decay involves real human stories that deserve dignity and respect.

Conclusion: A Window into the Past

The Howell Building in Milledgeville, Georgia, stands as more than just another entry in the catalog of abandoned places in Georgia. Built in 1939 during the expansion of what would become the world’s largest mental institution, it operated for barely three decades before abandonment claimed it in the early 1970s. Today, it decays slowly, vines crawling up its walls, windows broken, roof collapsing—a physical manifestation of the rise and fall of institutional mental health care in America.

For urban explorers, historians, photographers, and anyone interested in understanding how society has treated mental illness, the Howell Building offers powerful lessons. It reminds us that progress isn’t linear, that well-intentioned systems can cause tremendous harm, and that our current approaches to mental health care evolved through trial, error, and the suffering of countless individuals.

As you explore abandoned sites throughout Georgia, or simply learn about them from afar, remember that each structure tells a story. The Howell Building’s story speaks of expansion and abandonment, of treatment and abuse, of changing philosophies and incomplete solutions. It’s a story that continues today, as we still struggle to provide appropriate mental health care and support to those who need it.

The next time you find yourself exploring URBEX opportunities in Georgia, or researching abandoned places from the comfort of home, take a moment to consider the Howell Building and what it represents. Behind every broken window and collapsed roof lies a history worth understanding, preserving, and learning from—even as nature slowly reclaims the structures we leave behind.

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in learning about the nearby abandoned Holly Building at Scott State Prison, the Cypress Knee Museum in Florida, or the Tsiranavor Church of Ashtarak all the way in Armenia.

A 360-degree panoramic image inside the abandoned Howell Building at the old Central State Hospital in Milledgeville, Georgia. Photo by the Abandoned in 360 URBEX Team.

Inside the Howell Building at Central State Hospital

The following images document the abandoned Howell Building, a structure that stands as a silent testament to a bygone era. Once a thriving hub of activity, the building now languishes in neglect, its empty corridors and deteriorating facade bearing witness to the passage of time. Each photograph captures the haunting beauty of architectural decay, revealing details that speak to both the building’s former grandeur and its present state of abandonment.

Through these images, viewers are invited to explore the forgotten spaces of the Howell Building, where peeling paint, broken windows, and shadowed interiors tell stories of what once was. The documentation serves not only as a visual record of urban decay but also as a poignant reminder of how quickly prosperity can fade when structures are left to the elements and the relentless march of time.

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Equipment used to capture the 360-degree panoramic images:

- Canon DSLR camera

- Canon 8-15mm fisheye

- Manfrotto tripod

- Custom rotating tripod head

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.