The Abandoned Alan Kemper Building at Scott State Prison, Milledgeville, GA – An Urbex Adventure

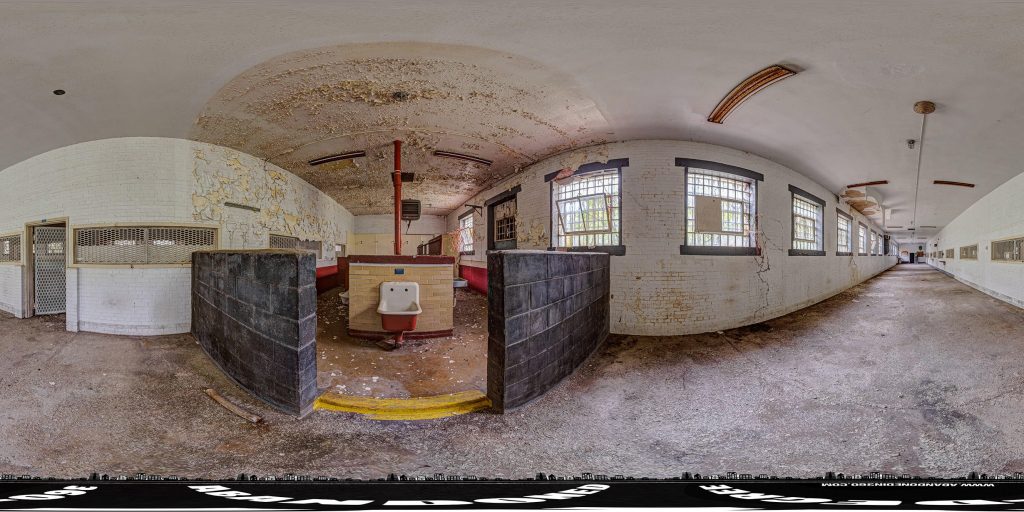

Step inside the abandoned Alan Kemper Building at Scott State Prison in Milledgeville, Georgia, and experience the haunting atmosphere of this forgotten structure from your screen. Cracked walls, peeling paint, and long, silent corridors tell the story of a facility left behind by time, yet still full of character for urban explorers who are drawn to decay, history, and mystery.

Use the immersive 16-image panoramic 360-degree virtual tour below to explore every angle in detail. Move through the space at your own pace as you study each room, doorway, and passageway—almost as if you’re walking the site in person, but with the comfort and safety of viewing it from home.

Click here to view it in fullscreen.

Located within the old Central State Hospital campus (near Milledgeville’s Hardwick area), the Alan Kemper Building is a remarkable relic of Georgia’s past. Today it sits deserted and decaying behind chain-link fences, yet still imposing with its two-story brick façade. Once a 59,436-square-foot complex, it alternately housed mental hospital patients and prison inmates. Urban explorers now revere Kemper as one of Georgia’s top abandoned in Georgia destinations, thanks to its graffiti-covered halls and broken windows. By day the sun filters through the gaps, peeling paint and scattered remnants of beds and papers glow in the light. At dusk the silence turns eerie. Visitors report finding old inmate belongings underfoot and medical equipment long left behind.

This blog traces Kemper Building’s full story: from its construction to its various uses and eventual abandonment. We include historical facts and timelines, and (as instructed) end with practical tips for adventurous urban explorers. All key facts are cited from reliable sources, including historical reports and news articles.

Timeline of the Alan Kemper Building

-

1937: Constructed as part of Central State Hospital’s expansion. The Alan Kemper Building opened as a large red-brick hospital wing (59,436 sq ft, two floors) on the Central State campus. At that time it served psychiatric patients (likely segregated by race/gender, as was common then), though exact records of its initial use are sparse.

-

1958–1972: Converted to a maximum-security men’s prison. Georgia moved its male inmates from the aging Colony Farm Prison in 1958, and Kemper became the state’s toughest prison block. All prisoners were locked in; the once-hospital wing got steel cell doors and barred windows. Anecdotes from this era describe Kemper as grim and “depressing,” reserved for violent offenders.

-

1967: Georgia integrated its prison system, and all inmates from Colony Farm (of every race) were consolidated in Kemper. Kemper was then overcrowded, but it remained the supermax wing for men. Notably, reporters like Jack Nelson won a Pulitzer in 1960 for exposing patient abuse at Central State – Kemper had by then ceased patient housing, but its location tied it to that scandal’s legacy.

-

1972–1974: Re-purposed briefly for women. The building was transferred to the state corrections department in 1972, and became part of the new Georgia Rehabilitation Center for Women. Female inmates were housed here, relieving overcrowding at other women’s prisons. In 1974, when a new women’s prison (the Ingram Building) opened on campus, all female inmates were moved out of Kemper. After 1974, Kemper sat largely unused for several years.

-

1981–2009: Part of Scott State Prison. In 1981 the state opened a modern medium-security prison named Frank C. Scott Jr. State Prison (often just “Scott State”) on the same grounds. The old hospital wings were incorporated into this complex. Kemper became the intake and maximum-security building for Scott State. All new prisoners were processed here, and the most dangerous offenders (including death-row inmates awaiting execution) were locked in Kemper’s small cells. Holly and Ingram housed lower-security inmates. This era left Kemper with graffiti, oil stains, and still-intact industrial features from the 1980s.

-

2009: Prison closure. In July 2009 Georgia’s Corrections Dept. announced it would close Scott State (and two other prisons) to cut costs. By August 15, 2009, Scott State Prison was shut down. Almost 1,800 inmates were transferred to other prisons. The closure was blamed on the facility’s age (built 1937) and maintenance costs. About 250–300 local jobs disappeared overnight, marking a tough blow to the Milledgeville economy.

-

Present: Abandoned landmark. Today the Alan Kemper Building stands empty as part of the Renaissance Park redevelopment (the new name for the old hospital campus). Holly and Ingram have been sold for other uses, but Kemper (and its two adjacent guard towers) remain unused. It was never officially renamed – its only other moniker was the informal “Intake Building” under Scott State. In stray references, locals might just call it “Old Scott Prison.”

Kemper’s story reflects larger trends: by the 1960s Central State Hospital held nearly 12,000 patients, but mental healthcare reforms led to its downsizing and closure by 2010. Likewise, Georgia’s prison population shifted, and older facilities like Scott State were phased out. Amid these changes, Kemper transitioned through multiple roles, finally ending up as a haunting abandoned in Georgia attraction.

Origins and Construction of the Alan Kemper Building (1937)

The Alan Kemper Building was erected in 1937, during the Great Depression, as the Central State Hospital expanded. Central State (founded 1842) was Georgia’s main mental hospital, and by the 1930s it needed more space. Kemper was built as a sturdy, permanent structure on the campus. Its design reflects 1930s institutional architecture: thick red-brick walls, a flat roof, and narrow, vertically aligned windows. At two stories tall, with wide corridors and high ceilings, it resembled a cross between a hospital ward and a fortress.

According to a commercial listing, Kemper covered 59,436 square feet over two floors. The exterior offered little ornamentation – no Greek columns or fancy details, just solid construction. Entering the front doors (now often pried open or missing), one finds a long central hall. The hallway floors were originally tiled or linoleum, but are now worn concrete. The walls, painted institutional white, are peeling. In winter the building is cold; in summer it is sweltering. Large steel staircases rise at each end.

In 1937, Segregation was still in force, so Central State’s buildings were arranged by race. It’s likely Kemper originally housed either white or Black patients (records are unclear). The interior suggests some cells and more open wards. Some hospital historians believe Kemper may have been used for convalescing or long-term patients. Regardless, its structure – with secure rooms and clinics – later made conversion to a prison relatively easy.

For now, however, Kemper was a hospital building. By the 1950s Central State encompassed dozens of buildings. Kemper blended in with its brick neighbors. It had no special name at first; some records simply call it “Kemper Building” (possibly named for a Dr. John C. Kemper, who was on staff then). By 1958, though, everything would change.

From Hospital Ward to Men’s Prison (1958–1972)

In the late 1950s, Georgia’s state leaders decided to move male inmates off the Colony Farm site and onto the Milledgeville campus. Kemper was chosen as their new prison wing. Thus in 1958 the Kemper Building shed its hospital role and became a maximum-security prison for men. All doors were locked; nurses were replaced by guards.

From 1958 through 1972, Kemper housed the state’s most dangerous prisoners. It earned a reputation for strict conditions. An OJP report notes that Kemper “served as a maximum security prison for men from 1958–1972”. Among its inmates were murderers and rapists. Some went on to die under Georgia’s then-active death penalty. Rumors (unsupported by official records) say that condemned inmates spent their final days in Kemper’s cells. The corridors were reportedly considered “ugly, depressing and totally inadequate” for any purpose – a grim home for a grim population.

By 1967, Georgia integrated its corrections system. That year all inmates from Colony Farm (of every race) were consolidated into Kemper. The inmate count swelled: contemporary reports say Scott State (then just Kemper and a few buildings) held about 1,784 prisoners. Guards at Kemper walked very tight security. The open yard was small, surrounded by razor wire; cells had solid bunk beds and meshed metal doors. (An old grid pattern on the floor was where the flagpole stood, so even the national flag was flown inside the prison yard.)

Despite its prison role, Kemper’s history remained tied to Central State. In fact, 1960 saw a famous scandal: The Atlanta Constitution exposed patient abuse at the hospital, earning a Pulitzer. Although Kemper was by then a prison, its proximity meant it lived under the shadow of that exposé. No physical change in Kemper was mandated by that scandal, but it underscored how Milledgeville’s institutions were intertwined.

In summary, 1958–1972 was Kemper’s toughest era. It was the maximum-security men’s wing, and its name on prison forms was simply “Kemper.” The building had no other nickname yet. For inmates, a trip to Kemper meant the highest level of custody.

Women’s Facility (1972–1974)

In 1972 Georgia reorganized its prisons. The Department of Corrections (now “Offender Rehabilitation”) took over Kemper from the State Hospital. Around this time, the state turned the Kemper Building into a women’s prison wing. It was renamed the Georgia Rehabilitation Center for Women on the Milledgeville campus (though the building itself was still called Kemper). This gave extra space for female inmates, who until then had cramped conditions elsewhere.

This women’s phase was short. In 1974 a brand-new women’s prison (the Ingram Building) opened on the same property. Once Ingram was ready, all female inmates were moved out of Kemper into Ingram. The move completed the segregation reforms: from then on, women stayed in their own facility, and men in theirs. Kemper, now empty, briefly served no inmates. Its mission as a women’s center had ended. Apart from a few administrative uses (storage, offices), the building sat vacant for the rest of the 1970s.

By 1975, locals mostly associated Kemper with men’s prison work again. It had no popular new name. Officially, it was unused property. (Some internal memos called it “Kemper Building – Vacancy”). Over the next five years, the state considered what to do with the space. Ultimately, it chose to revive Kemper as part of a new adult prison complex, rather than tear it down.

Scott State Prison Era (1981–2009)

The next major change came in 1981. Georgia constructed a modern medium-security prison on the Central State grounds, named Frank C. Scott Jr. State Prison. Scott State re-used the old hospital buildings as the prison complex: Holly, Ingram, and Kemper. Scott State’s official name honored a fallen officer, but everyone called it “Scott State Prison” or just “Scott.” With this opening, the Alan Kemper Building finally found a long-term role again: it became Kemper, Intake Building.

Under Scott State, Kemper housed newly arriving inmates for processing and classification. Every prisoner – whether from county jail or parole return – passed through Kemper first. If an inmate was deemed maximum-security, he stayed in Kemper’s cells. Otherwise he was quickly moved to Holly or Ingram. In practice, Kemper again held the toughest guys. According to former corrections officers, “Kemper Building housed the most violent inmates” of the complex.

Notably, 1980s Scott State saw nearly 200 executions (Georgia had reinstated the death penalty). Most of those condemned men came through Kemper before they died. The building’s reputation as home to Georgia’s “worst of the worst” was cemented. However, Scott State also added new facilities around Kemper – like a central control office, a small gym and chapel in Holly, and an updated dining hall outside Kemper – so Kemper itself stayed much as it was in 1974. Its cells, walkways, and industrial fixtures persisted.

Into the 1990s and 2000s, Kemper remained in steady use. Photographs from those decades show the same steel beds and green paint as in the 1960s, just a little more faded. The statewide prison population peaked in the 1990s, but by the 2000s reforms and new prisons elsewhere meant Scott State was aging out. There were no famous escapes or riots at Kemper; it was a secure block. Yet as the costs of running old buildings grew, state officials eyed closures.

Closure and Abandonment (2009–Present)

In mid-2009, Georgia announced a plan to shut down two Milledgeville prisons. Scott State (Frank C. Scott Jr. Prison) was one of them. The administration cited the prisons’ age and cost; Scott State’s birth year (1937) was noted as a factor. On August 15, 2009, the gates of Scott State locked for the last time. Nearly 1,800 prisoners were shipped to other facilities. According to the official statement, this closure would save the state about $10 million per year. Around 281 correctional staff lost their jobs at once. Local news later estimated that Scott’s closure alone cost roughly 250–300 area jobs.

With the prison closed, the Alan Kemper Building was left vacant. For a while, state planners discussed selling or reusing the Scott State buildings. By 2019 the city rebranded the entire campus “Renaissance Park,” hoping to attract business and technology firms. Indeed, listing services in 2024 showed all three prison wings (Holly, Ingram, Kemper) as vacant industrial properties. Holly and Ingram have since been sold or leased for other purposes (some medical/office plans), but the Kemper Building itself has not been redeveloped.

Today Kemper stands fenced off, with “FOR SALE” signs nearby. Vines and trees nibble at its foundation. Many windows are broken, and graffiti (from over 15 years of vacancy) covers much of the interior. The sad sight of iron cell doors and derelict dormitories reminds visitors of the building’s former life. It has no current use. Urban explorers report that people sometimes squat inside or light fires, but it is not maintained. The city considers it part of its historic landscape.

Throughout all these changes, Kemper kept its name. It never had an alternate official name beyond “Alan Kemper Building.” In corrections lingo it was sometimes just “Kemper” or “the Intake Building,” but those were never formal titles. The state calls the property by the larger prison name (Frank C. Scott Jr. State Prison, or now Renaissance Park). So in writing about it, we’ll stick with Alan Kemper Building – the name it has worn for decades.

Architecture and Interior Features of the Alan Kemper Building

The Alan Kemper Building’s physical design tells its story. Its exterior is plain but solid: red brick walls and a flat, tin-covered roof, all trimmed in concrete. Narrow, barred windows sit high on the walls. There’s no frontage or sign now (there used to be a guard shack outside). The building’s footprint (59,436 sq ft) is roughly the size of a large supermarket.

Inside, the layout still reflects its 1930s design. A long main corridor runs the length of the building, about 8–10 feet wide. On either side are dozens of small cells or rooms. The corridor ceiling is about 10–12 feet high; the paint and plaster hang in ragged strips. Old fluorescent light fixtures and exposed conduit snake along the ceiling. Many fixtures are broken or missing, so today only natural light (from busted windows or doorways) illuminates the halls.

Each cell is just big enough for a metal bunkbed and an integrated toilet/sink unit. The bunks are still bolted to the floor, though rusted. In some cells the bottom bunk frame is missing; in others it’s a twisted wreck. The concrete floors of the cells show where the mattresses and steel lockers once rested. On one wall of each cell is a tiny steel-grated window to the corridor and a slot for passing food trays. Those pass-through slots and window bars are all still there, now mostly open. The cell doors (several still hanging on hinges) were heavy steel plates with a 2-foot by 3-foot barred window.

On the second floor (accessed by two metal staircases), the arrangement is similar. Upper halls contain cells and a few larger rooms that were probably offices or clinics. In one upstairs corner sits an old jailor’s kiosk with bulletproof glass (now cracked or missing). Nearby is a faded chalkboard frame where daily counts were once written. Offices along the second floor hall have broken windows and overturned desks inside.

The basement and mechanical area hold more curiosities. There, one can find vault-like rooms that may have been jailer offices or record storage. Explorers report finding mail-slot boxes on the wall (inmates would have collected letters here). In the old boiler room, the equipment is gone but coal dust and rust outline remains. There is even an old hand-cranked elevator shaft (now filled with debris).

Outside, the exercise yard is a mess. A cracked concrete lot is ringed by fallen chain-link fence. The original fence posts and uprights remain, some still wrapped in coils of barbed wire that once topped the walls. On one corner stands the base of an old guard tower – the metal support skeleton is still there, though the wooden cabin is gone. A weathered sign on a fence post still reads “Scott State Prison – KEEP OUT.”

Everywhere inside Kemper are reminders of its past uses. On the walls someone scrawled “FREE SCOTT” in faded blue paint (likely a 1970s protest about inmates’ rights). Old flyers advertising GED classes or chapel services are mostly torn away, but one can find a fragment with “Lord…Love You” on it. In several spots, stenciled floor markings from the 1960s (like arrowed “EXIT” or floor numbers) peek out under graffiti layers. Even the plumbing is intact – rusted toilets and sinks sit in cells, and drain lines run across corridors.

In short, Kemper is a well-preserved time capsule of a mid-20th-century prison. For architecture buffs and photographers, it offers a haunting glimpse of history. The hard angles and shadows inside are striking: small details like a broken ceiling vent or an embossed plaque reading “Dept. of Offender Rehab – Kemper Bldg” excite those who notice. It may be dingy, but every corner of Kemper tells a story of its institutional past.

Economic and Community Impact

In its heyday, the entire Milledgeville complex (Central State Hospital and its prisons) was one of Baldwin County’s biggest employers. In the 1970s–’90s thousands of local people worked there. When Scott State Prison closed in 2009, the loss was keenly felt. Official reports noted that closing Scott State alone saved the state $10 million per year, but local news pointed out that about 250–300 jobs vanished as a result. These workers were nurses, guards, counselors and support staff – many had worked there for decades.

This economic blow was compounded in 2010 and beyond when other nearby prisons also closed. By then the Central State Hospital had cut its patient population dramatically (it held ~12,000 in 1960), and the old asylum facilities were being repurposed or shut down. In 2010 Georgia’s hospital system announced the final closure of Central State’s patient wards. Baldwin County shifted from “prison town” back to a sleepy retirement-age city.

Today local planners have high hopes for Renaissance Park (the campus’s new identity). They want health care clinics, technical institutes, maybe light manufacturing. But the old prison wings – including Kemper – are hard to repurpose. Officials have noted that renovating a 1937 prison with asbestos and security features would cost many millions. As a result, proposals to turn Kemper into a museum or community center have not materialized. It remains, for the time being, a reminder of Milledgeville’s past era.

For the local economy and memory, Kemper is a symbol. Where once men (and even women) labored to keep the prison running, now photographers and ghost hunters wander. The scarcity of jobs means many of Kemper’s former colleagues now work elsewhere. At least one local historical society has collected oral histories from ex-employees, preserving tales of daily life inside Kemper. They recall white-uniformed inmate uniforms, lockup schedules, and daily yard time. These stories, though anecdotal, add color to the dry facts: Kemper was once part of a living community.

In Popular Culture and Memory

Though not famous nationwide, the Alan Kemper Building has a niche in regional lore. It regularly appears on Georgia urban-exploration blogs and YouTube channels. Amateur videos show drone flyovers and inside tours, usually titled things like “Abandoned Scott State Prison – Kemper Building”. These videos often dub the building as “Milledgeville Prison” or simply “Scott State Prison,” reflecting how Kemper’s identity is mixed up with the larger complex.

On forums and social media, Kemper is tagged with #urbex, #abandonedga, and #prisons. Some local videographers have posted night-vision clips claiming (dramatically) to sense ghostly presences among the cells. In reality, there are no documented hauntings – but urban legends do circulate. One story claims you can hear distant voices in the hallway at night; another says a phantom guard still walks the wing. Such tales are common around old asylums and prisons, though none of these have verifiable evidence.

Georgia’s historical records preserve snippets of Kemper’s past. For example, period photos in state archives show inmates working in the yard outside what is clearly the Kemper Building. A 1955 photo captures a mobile X-ray van parked beside its wing. There are even color snapshots (1970s) of Christmas decorations in the cafeteria that served Kemper’s inmates. These archived images remind us that Kemper once hosted thousands of real people’s lives – clinicians, prisoners, guards. Now its halls are quiet.

Among historians, Central State’s old prison buildings are sometimes studied as a group. They are unusual because they trace the shift from the old asylum model to the modern prison system. Architecture scholars note that the 1930s designs (like Kemper) were meant to be permanent facilities. In Milledgeville the brick dormitories of Kemper and Holly stand next to century-old asylum buildings (e.g. the former Powell building). This juxtaposition of 19th- and 20th-century institutional design is rare.

Interestingly, the name “Kemper Building” persists largely due to urbex interest. Redevelopment plans rarely mention it by name; reports typically refer to “Building A” or just include it in “the old prison complex.” But in ghost-hunter circles the name “Kemper Building” is well-known. Some online maps (erroneously) label the area “Rivers State Prison” or “Men’s State,” but local explorers insist on calling it Kemper. It’s now part of Milledgeville’s identity as an urbex destination.

Visitor Tips (Urban Exploration Guidance)

-

Respect the law: The Kemper Building is on state land (part of “Renaissance Park”). Officially it’s closed. Entering is trespassing. If you choose to explore, do so at your own risk. Many urbexers suggest a low profile: avoid drawing attention, and leave quietly if confronted.

-

Bring proper gear: Wear sturdy boots (metal debris and uneven floors are hazards). Gloves can protect from rust and broken edges. Carry a bright flashlight (and spare batteries) – virtually no interior lighting works. A hardhat or at least a baseball cap can help shield from falling plaster or cobwebs. Consider a dust mask if you’re sensitive to mold or asbestos (though major asbestos has reportedly been removed).

-

Never go alone: At least two people should explore together. Let a third friend or family member know your plans and expected return time. Don’t rely on cell phones – signal is weak inside thick walls. Walkie-talkies (if you have them) can be handy.

-

Watch your step: Floors can be slippery or unstable. Test any stair or floorboard before putting full weight on it. Avoid areas where the ceiling appears sunken or cracked. Keep to the main corridors initially until you’re confident of the structure.

-

Be mindful of hazards: Broken glass, jagged metal, exposed wiring, and old nails can injure you. Some sections may flood or accumulate ice in winter; check weather forecasts. Wildlife like bats, raccoons, snakes or spiders might be present. Wear long sleeves and bug spray. Check for ticks afterward.

-

Respect safety: Don’t smoke (old buildings can hide flammable materials). Avoid leaning on old railings. If you see any sign of structural collapse or major damage, retreat. These ruins are unsafe in parts, so caution is vital.

-

Take nothing but pictures: Do not graffiti, carve, or remove artifacts. Urban exploration ethics discourage new vandalism. Many still-pristine relics (vintage signs, paperwork, plaques) remain. Help preserve them.

-

Best times to visit: Go in daytime for safety; it’s no less abandoned at night, but fewer explorers do night missions here due to the risk. Early morning or late afternoon light creates dramatic shadows for photos. Plan for a few hours at least to see all three levels.

-

Parking and access: There is no official lot. Park well off Lawrence Road to avoid obstructing traffic. Many explorers park near the old hospital gate and walk in. Be discreet and respectful of nearby homes.

-

Drone caution: Drones are often disabled on state property. If you fly, do so from public streets only (airspace isn’t private property, but be aware of local UAV laws). Alternatively, take selfies and handheld shots.

-

Stay healthy: Bring water and snacks; the building has no facilities. Wear a wristwatch to track time (you can lose track in such places). After exiting, wash hands and clothes – old buildings can harbor bacteria or mold.

By following these tips, urban explorers can safely experience the Kemper Building’s eerie atmosphere. It is a rare surviving piece of Georgia history, and should be treated with both curiosity and caution.

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in virtually exploring the Ocmulgee River Train Swing Bridge in Georgia, the Welch Spring Hospital Ruins in Missouri, or the Historic Alabama Capitol in Alabama.

A 360-degree panoramic image captured inside the abandoned Alan Kemper Building at the Scott State Prison in Milledgeville, Georgia. Photo by the Abandoned in 360 URBEX Team

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Equipment used to capture the 360-degree panoramic images:

- Canon DSLR camera

- Canon 8-15mm fisheye

- Manfrotto tripod

- Custom rotating tripod head

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.