Urban Exploring the Abandoned Santa Fe Railroad Terminus at Point Richmond, California

Explore the historic Santa Fe railroad terminus at Point Richmond in Richmond, California, a spot that once pulsed with rail activity and now sits in quiet decay—perfect for URBEX enthusiasts and history-loving urban explorers. This former terminal is a reminder of California’s transportation past, where tracks, industry, and the Bayfront all met in one place, leaving behind weathered structures, industrial textures, and that unmistakable abandoned energy.

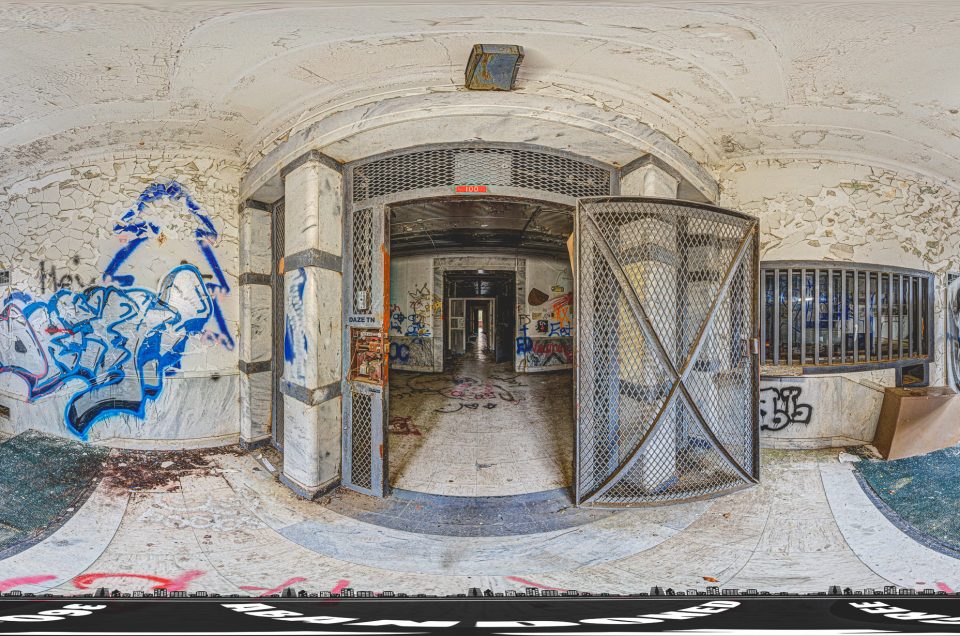

Take a look inside the Santa Fe railroad terminus at Point Richmond with the amazing 360-degree panoramic images below on Google Maps Street View. Use the virtual tour to study details, plan your exploration, and appreciate how time has transformed this location into a photogenic, atmospheric site that still tells its story.

Photo by: Milo4u2c

Photo by: Darren Kitchen

Santa Fe Railroad Terminus at Point Richmond

Nestled on a windswept spit of land in Richmond, California, lies a forgotten railroad terminus that once linked the American continent to San Francisco Bay. The Santa Fe railroad terminus at Point Richmond – now an abandoned in California relic – is a tantalizing site for history buffs and urban explorers alike. In its heyday, this ferry terminal bustled with steam locomotives, railcars, and passengers making the last leg of a transcontinental journey by boat. Today, its crumbling piers, graffiti-clad structures, and lonely tracks tell a story of grand ambitions and inevitable change. In this blog post, we’ll journey through the rise, fall, and rediscovery of this historic site – an URBEX adventure through time, where rusted iron and rotting wood meet salty air and Bay Area skyline.

The Birth of a Transcontinental Terminus

In the late 19th century, visionaries set their sights on Point Richmond as the ideal western terminus for a new transcontinental railroad. In 1895, entrepreneur Augustin S. Macdonald imagined a direct rail link from the heart of America to the shores of San Francisco Bay. He pitched the idea to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, which was then expanding westward. Santa Fe leaders agreed, seeing an opportunity to establish a presence on the Bay and directly challenge other railroads. By 1899, construction was underway on a massive pier at Point Richmond – a structure that would allow entire trains to roll right up to the water’s edge. This pier, completed around 1900, was built for a revolutionary purpose: to load railroad cars onto ferry barges for transport across the bay. In fact, it became the first port on the U.S. West Coast to directly transfer railcars onto boats, a cutting-edge innovation for its time.

When the first overland passenger train arrived from Chicago in 1900, Richmond officially became the Santa Fe Railway’s western terminus. The Point Richmond site – later dubbed Ferry Point – sprang to life with activity. Santa Fe established a sprawling rail yard adjacent to the pier, complete with maintenance shops and roundhouses by 1901. At the same time, industry followed the rails: Standard Oil (now Chevron) built a large refinery in 1901 just east of the terminal, taking advantage of the easy rail and ferry access. A tunnel was bored through the nearby Potrero San Pablo ridge to connect the new yard with the rest of Santa Fe’s tracks inland. Trains would shoot through this 300-meter tunnel and emerge by the bay, where the awaiting ferry slip stood ready. The stage was set for Point Richmond to become a thriving interchange between land and sea.

Ferryboats, Trains, and a Thriving Hub

From 1900 through the 1920s, the Santa Fe railroad terminus at Point Richmond thrived as a unique intermodal hub. Steam locomotives chugged into the yard hauling passenger coaches and freight cars from as far away as the Midwest. At Ferry Point, crews would position the railcars onto a specialized ferry slip – essentially a movable bridge that could be raised or lowered to meet a ferry boat deck. Here, passengers disembarked and walked onto comfortable ferryboats bound for San Francisco, while entire freight cars were rolled onto barges. It was a marvel of engineering and logistics: by ferrying across the bay, Santa Fe offered a direct route into San Francisco without needing a land connection. This made Richmond an important gateway. Travelers from the East could ride a Santa Fe train to Point Richmond, then sail across the picturesque bay to the Ferry Building in San Francisco – experiencing two modes of transport in one seamless journey.

The ferry operation at Point Richmond quickly became a bustling enterprise. Santa Fe chose this spot in part because the waters off Point Richmond were naturally deep, allowing large ferryboats to dock regularly. The railroad operated its own fleet of tugboats and barge ferries to haul railcars. Early on, steam-powered ferries carried both people and rail freight. By the mid-20th century, a trio of dedicated Santa Fe tugboats – the Paul P. Hastings, Edward J. Engel, and John R. Hayden – towed massive barges that could hold up to fourteen railcars at a time across the bay. This terminal became the first stop in California for goods from the Santa Fe line. Everything from Midwestern grain to manufactured goods, and even oil from the adjacent refinery, could be loaded onto ships here. Richmond’s emergence as an industrial town owed much to this terminal; by 1910, just a few years after the terminal opened, the city’s population had swelled and numerous factories had set up shop in the area.

At its peak, Ferry Point bustled day and night. Passengers in smart early-1900s attire mingled with longshoremen loading cargo. The air would have been filled with the smells of coal smoke and saltwater, and the sounds of screeching metal wheels and steam whistles echoing across the bay. Trains arriving from the East would halt at a handsome two-story Craftsman-style Richmond Santa Fe Depot near the yard. From there, a short shuttle brought passengers to the waterfront ferry pier. As they stepped onto the boat, they could gaze back at the sprawling Santa Fe yard, where switch engines sorted freight cars destined for the barge. This innovative system effectively made Point Richmond an extension of Santa Fe’s transcontinental railroad – a railroad ferry terminus unlike any other in California.

Competition, Bridges, and the End of Passenger Service

The prosperity of the Santa Fe’s ferry terminus did not go unchallenged. Other railroads and transit companies also relied on ferryboats to link the Bay Area before bridges existed. The Southern Pacific Railroad, Santa Fe’s rival, operated its own extensive ferry network out of the Oakland Mole (a long pier in Oakland) to ferry trains and passengers to San Francisco. By the 1920s, motor vehicles and independent ferry lines (like the Key System for commuters) were also vying for bay traffic. Santa Fe’s ferry link faced stiff competition from other ferry services, which gradually eroded its unique advantage.

The final blow to Santa Fe’s passenger ferry service came in the 1930s with a pair of monumental engineering achievements: the Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge. In November 1936, the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge opened, allowing automobiles (and later trains via Key System) to cross the bay directly. Suddenly, travelers had a faster, all-land route into San Francisco by driving or taking a bus over the new bridge. Santa Fe saw the writing on the wall. In fact, even before the Bay Bridge’s completion, Santa Fe made a strategic shift: on April 23, 1933, it halted its own ferryboats from Point Richmond and began routing its trains to connect with Southern Pacific’s ferries at Oakland instead. This cooperation meant Santa Fe passengers would disembark in Oakland and ride an SP ferry the short distance to San Francisco, rather than Santa Fe running a parallel ferry from Richmond. By the mid-1930s, the elegant ferry steamers that once departed Ferry Point with crowds of travelers were discontinued. The Great Depression era and new bridges had effectively ended the need for Santa Fe’s dedicated passenger ferry.

After 1933, the Santa Fe terminus at Point Richmond transitioned to a freight-focused facility. The grand era of rail-and-ferry passenger travel from that spot was over, a victim of infrastructure progress and competition. But that didn’t mean Ferry Point went quiet just yet. Santa Fe still owned the yard and pier, and there was plenty of freight business to justify keeping the ferry slip active for cargo. Moreover, during World War II, the old ferry terminal saw a resurgence of activity: it was used to transport military troops and equipment. Troop trains would arrive at Richmond, and soldiers would board ferries bound for San Francisco, where they could be transferred to ocean-going ships heading to the Pacific theater. In those war years of the early 1940s, Ferry Point once again thrummed with life – this time, carrying GIs and jeeps instead of tourists with trunks and Model T’s.

From Freight Floats to Final Closure

The decades after WWII saw enormous changes in transportation, and the Point Richmond ferry terminal gradually slid into obsolescence. Freight ferries continued to run through the 1950s and 1960s, but new options were emerging. The interstate highway system allowed trucks to carry cargo around the Bay Area bridges, and railroads found alternate interchange routes. For instance, by the late 1950s Santa Fe built a branch line into Oakland and arranged bus connections over the Bay Bridge for passengers. The railroad also had some isolated track in San Francisco accessible via barge, but overall, piggyback trucking and direct rail routes were reducing the need to float entire railcars across water. One by one, Santa Fe’s fleet of tugboats was sold off as traffic declined. By 1969, only one of the three main tugs remained in service. The railroad pier at Point Richmond, once vital, started to feel increasingly ghostly – used only sporadically as the years went on.

Yet, some freight continued to move via Ferry Point into the 1970s. Notably, chemical tank cars and specialty cargo still needed to reach customers in San Francisco. (For example, chlorine tankers for city water treatment and newsprint boxcars for the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper were known cargos on the barges.) In one famous incident, a railcar tanker loaded with whiskey barrels rolled off a barge in mid-bay during foul weather, sending a cache of Kessler Whiskey to the bottom of the bay. Anecdotes like that became part of local lore, illustrating the quirks of this unusual ferry operation. By the early 1970s, however, the writing was on the wall for Ferry Point.

Regular freight service to the Richmond ferry slip finally ceased in 1975, making it the last of the old transcontinental railroad wharves on San Francisco Bay to shut down. For roughly 75 years, this pier had served the nation’s trains; now it was no longer needed. Santa Fe’s last tugboat, the venerable Paul P. Hastings, kept running in a limited capacity until the mid-80s, just in case – a testament to how reluctant the railroad was to completely give up the old ways. But fate intervened one spring day: on May 4, 1984, a blaze broke out on the abandoned Richmond ferry slip. The fire raged through the wooden timbers of the pier, severely damaging the structure and effectively killing off the remaining cross-bay float service. After the 1984 fire, Santa Fe finally threw in the towel and sold the last tugboat. The era of rail ferries on the Bay was truly over.

Abandonment and Decay of Ferry Point

With operations discontinued, the Santa Fe terminus at Point Richmond was left to the elements. For a while, the site just sat idle on the edge of the bay, a silent graveyard of rusting rails and charred pilings. The pier that had once been the gateway to San Francisco was now broken – literally. The 1984 fire had destroyed a section of the trestle, leaving the outer half of the pier isolated from land by a gap of missing deck. All that remained were blackened wooden pilings sticking out of the water and a truncated pier stem that ended abruptly in open bay. The ferry slip’s metal components – once capable of raising and lowering an entire rail deck – were twisted and weathered, but some parts still clung to the frame. To anyone peering from shore, the derelict appearance of Ferry Point was striking; it truly looked like the end of the line.

On land, the once-busy Santa Fe rail yard in Richmond also wound down. By the late 1980s, Santa Fe Railway (which would later merge into BNSF) no longer needed the vast acreage by the waterfront. In 1991, the East Bay Regional Park District acquired much of the old right-of-way and waterfront property. The goal was to incorporate this scenic peninsula into a public park. Over the years, the area around Ferry Point was transformed into the Miller/Knox Regional Shoreline, a beautiful waterfront park featuring trails, picnic areas, and a fishing pier. In fact, part of the historic ferry pier was restored for public use – the section closest to shore was rebuilt so visitors can stroll out over the water and even cast fishing lines, all while enjoying panoramic views of San Francisco across the bay. However, the outer portion of the pier, including the actual ferry slip mechanism, was left unrestored and fenced off. It remains in a state of picturesque ruin, accessible only to the birds perched on its rails and the waves lapping through its skeletal frame.

A few abandoned buildings from the terminal’s operational days still stand near the shore, just to the side of the pier. These low, concrete structures – once offices, a pump house, or perhaps a ferry terminal waiting room – have long since been deserted. They are now hollow shells with empty window frames staring out to the bay. Peering inside, you’ll find nothing but cracked concrete floors littered with debris, and walls plastered in graffiti left by generations of vandals and adventurers. Nature has started to reclaim parts of the site: salt spray accelerates the rust on metal fixtures, and hardy weeds poke through the old rail beds. Seagulls and pigeons roost in the eaves where railroad workers once clocked in for their shifts. The atmosphere is peaceful in its emptiness – a sharp contrast to the hustle and steam of a century ago.

Interestingly, a few relics have been preserved amid the decay. Along West Richmond Avenue where the rail line crossed the road, two old wig-wag crossing signals still stand guard, lovingly preserved as historic artifacts. These vintage warning signals – once clanging to stop traffic for trains – are among the last of their kind in America. And threading through the hillside nearby is the very tunnel that Santa Fe built in 1899. Amazingly, this tunnel is still there and open. Urban explorers can follow the old tracks right into the heart of the hill, traversing about 300 meters of cool, echoing darkness. Although the tunnel’s timbers and brickwork are over 120 years old, they continue to hold firm. Coming out the other end, you emerge at the Richmond side of the ridge, where the main line once continued east. Walking through this tunnel offers an immersive time-travel experience – it’s easy to imagine the ghostly rumble of a steam train ahead as you step over the same rails that carried Santa Fe locomotives so long ago.

An URBEX Adventure in the Present Day

Today, the abandoned Santa Fe railroad terminus at Point Richmond stands as a magnet for urban explorers in California. The site’s blend of historic significance and atmospheric decay makes it a must-see for those who love urban exploring in California’s Bay Area. Approaching Ferry Point in the present day, you’ll first notice the stunning natural setting. The point juts into San Francisco Bay, offering a sweeping vista: the Golden Gate Bridge often peeks out to the west on clear days, and the San Francisco skyline rises to the south across the water. Amid this scenery, the ruined pier stretches forlornly into the bay. From the public fishing pier (the restored section), one can gaze at the outer ruins: rusted rail tracks still visible on the dilapidated pier, and the jagged end where the fire cut it off. The old ferry slip’s pulley systems and pivot apparatus are also visible, giving a sense of how the structure once lifted and aligned heavy railcars onto boats. It’s a haunting sight – equal parts beautiful and melancholy – especially in the late afternoon light when the sun gilds the ruins in orange and the bay waves shimmer between the charred pilings.

For the intrepid explorer willing to (carefully) go off the beaten path, the real discoveries lie beyond the “Area Closed” signs and fences. Tucked beside the pier are the abandoned ferry terminal buildings mentioned earlier, which are officially off-limits but often tantalize curious visitors. Through broken doorways, you can see graffiti murals covering entire walls. Sunlight streams in through holes in the roof, illuminating the dust that hangs in the air. In some spots, if you look down, you’ll notice that sections of the concrete floor have collapsed, exposing sandy ground below – a reminder to tread cautiously. Climbing inside, you find that nearly all furnishings and equipment are long gone. Only the sturdy concrete frame remains, along with a few twisted pipes and bolts protruding from the walls. Every footstep echoes. The experience is both eerie and exhilarating: you’re standing in a space where railroad clerks once shuffled papers and travelers waited for ferries, but now it’s silent except for the distant crash of waves and the graffiti-tagged walls telling their own stories.

One particularly striking piece of graffiti art in these buildings is a large heart painted under a partly collapsed roof, known among local explorers for the way the light hits it at certain times of day. Moments like this – where art, decay, and nature intersect – embody the allure of URBEX at Ferry Point. It’s easy to see why the place ignites the imagination. As you step back outside the structure, you might notice old railroad ties and bits of metal hidden in the tall grass, remnants of sidings that once led into warehouses. Following the path of these tracks leads you toward the tunnel entrance, a concrete portal in the hillside that yawns like a doorway to another era. Many urban explorers count walking through this tunnel as a highlight of their visit. Inside, the air is damp and cool. The tunnel walls are coated in a century’s worth of soot and mineral deposits. Bring a flashlight or headlamp – about halfway through, it becomes pitch black, and you’ll be feeling your way over uneven ground (sometimes over puddles in winter). When you emerge on the far side, you’ve essentially crossed under the ridge that separated Ferry Point from the rest of Richmond – retracing the same route trains took when they headed inland.

Exploring Ferry Point offers a vivid lesson in California’s railroad history wrapped in an adventurous outing. There is a palpable sense of history hanging in the air here. Stand quietly at the water’s edge by the broken pier, and you can almost hear the faint echo of a steam whistle or the clank of a boxcar being ferried onto a barge. The site is a photographer’s dream, too. Whether it’s the geometric lines of the pier’s skeleton against a sunset, or the gritty textures of peeling paint and graffiti inside the pumphouse, there is no shortage of compelling visuals. Urban explorers should, of course, approach the site with respect and caution. Parts of the structures are unstable (there’s a reason they are fenced off), and one should be mindful of park regulations and safety. Even without venturing into off-limits areas, the park trails and authorized viewpoints provide plenty of intrigue. From the top of a nearby hill in Miller/Knox Park, you can look down and get a full panorama of Ferry Point: the once-grand causeway of commerce now reduced to a line of decaying timbers in the blue water.

Legacy of the Santa Fe railroad terminus at Point Richmond

The abandoned Santa Fe railroad terminus at Point Richmond may no longer serve trains and ferries, but its legacy lives on in multiple ways. For the city of Richmond, this terminal was the seed of its development – it put Richmond on the map as an industrial and transportation hub in the early 20th century. Without Santa Fe’s investment in 1899, Richmond might never have attracted the refinery and factories that followed. Every time a freight train rolls through Richmond today or a ship unloads at its port, it’s partly thanks to the path Santa Fe blazed over a century ago.

On a broader scale, Ferry Point stands as a monument to a bygone era of rail travel. It’s hard to imagine now, in an age of bridges and highways, that people once had to finish their cross-country train journey by boat. This terminus was a clever solution to the geography of the Bay – a reminder of how innovative the early railroad companies had to be to conquer natural barriers. It was also the last surviving railroad ferry terminal on San Francisco Bay, outliving others until 1975. As such, it has significant historical importance. In recognition of this, efforts have been made to document and preserve its story. Historical societies and rail enthusiasts have photographed the site and even saved artifacts (like those wig-wag signals and an old switch stand displayed nearby). The Richmond Museum of History houses photos and maps of Ferry Point in its prime, helping educate new generations about this chapter of transportation history.

For the urban exploration community, Ferry Point is a cherished spot – often listed among the top sites for urban exploring in California due to its combination of accessibility and rich backstory. It offers that perfect URBEX cocktail of thrill and education. You can test your nerve walking into dark tunnels or climbing crumbling structures, all while learning about how transformative this place once was. Many explorers come away with a deeper appreciation for how quickly the world can change: a vibrant terminal can become a ruin in just a few decades when its purpose is lost. There’s also a sense of poignancy. Standing on the cracked concrete of the pier, looking at the bay, one might reflect on the countless people and goods that passed through here – troops shipping out to war, immigrants arriving by train to start new lives in California, commuters and day-trippers in the Roaring Twenties – all these stories intersected at this now-abandoned spot.

In the end, the Santa Fe railroad terminus is more than just an abandoned place; it’s a time capsule of California’s evolution. Its construction in 1900 symbolized hope, progress, and the conquering of distance. Its abandonment by the 1970s symbolized changing technology and the relentless march of progress, as new infrastructure rendered the old obsolete. For urban explorers and history enthusiasts, visiting Ferry Point today is a chance to walk through history. Every rusting bolt and weathered board has a tale to tell. If you listen closely amid the quiet lapping of the bay, you might hear echoes of that tale – of locomotives and ferries, of ambition and adventure – carrying on the breeze. And as you leave, climbing out of the past and back into the present, you carry a piece of that story with you, inspired to seek out more hidden gems of abandoned California and keep their stories alive for the future.

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in learning about the Howell Building at Central State Hospital in Georgia, the abandoned Camp Beechwood in New York, or the Golf 4 Less store that was left to decay after a hurricane.

A 36-degree panoramic image captured at the abandoned Santa Fe Railroad Terminus at Point Richmond, California. Photo by: Darren Kitchen

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.