Exploring the Abandoned Antioch Baptist Church in Crawfordville, Georgia – A Historic URBEX Adventure

Explore the storied past of Antioch Baptist Church in Crawfordville, Georgia—a quiet sanctuary turned time capsule where peeling paint, stained-glass hues, and the hush of long-faded hymns set the tone for a thoughtful URBEX visit. This is a place for careful steps and curious minds, where every pew, pulpit, and timber beam hints at the congregation that once gathered here and the community history still clinging to the walls.

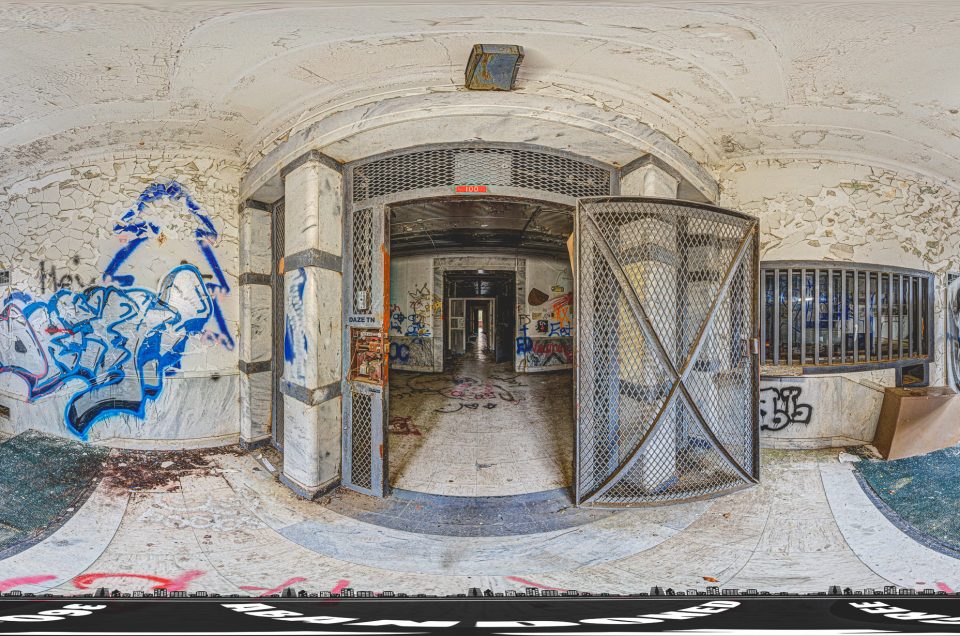

Ready to look around without disturbing a thing? Scroll to the amazing self-guided four-image 360-degree panoramic virtual tour below to study the chapel from aisle to rafters. Use it to plan a respectful exploration, note architectural details you might otherwise miss, and appreciate Antioch Baptist Church as it stands today—weathered, authentic, and full of quiet stories.

Click here to view it in fullscreen.

Tucked away on a quiet backroad in Taliaferro County, Georgia, the Antioch Baptist Church of Crawfordville is a captivating destination for fans of abandoned places and URBEX adventures. At first glance, this abandoned Georgia church presents an awe-inspiring sight: twin steepled towers in the Gothic Revival style rise above the treeline, guarding a weathered white sanctuary that has stood for well over a century. The structure’s striking design is unlike any other rural church of its era, making it immediately stand out to those passing by and earning it a reputation as possibly the most photographed church in Georgia. For those interested in urban exploring in Georgia, Antioch Baptist Church offers the perfect blend of historical intrigue, architectural beauty, and a touch of mystery.

Despite its forlorn appearance – peeling paint, sagging wood, and vines slowly creeping up its walls – Antioch Baptist Church is far from a forgotten ruin. In fact, this site is rich with history and remains cherished by descendants and history enthusiasts. Exploring this abandoned site in Georgia feels like stepping back in time: inside, sunlight filters through tall arched windows onto rows of hand-hewn wooden pews, and dust motes dance in the beams of light where congregants once gathered. The atmosphere is hauntingly peaceful. With an adventurous yet respectful spirit, we delve into the story of Antioch Baptist Church – from its founding by formerly enslaved Georgians, to its vibrant years of service, to the factors that led to its decline and abandonment. Along the way, we’ll uncover the church’s historical significance (including its role in local education and the Civil Rights Movement) and any legends or scandals that echo in its halls. Urban explorers (URBEX enthusiasts) and history buffs alike will find that urban exploring this site is not just about capturing a beautiful ruin on camera, but also about discovering the enduring legacy of a community and the resilience of a remarkable building.

Foundations of Antioch Baptist Church: Built by Freed Slaves

The story of Antioch Baptist Church begins in the aftermath of the Civil War, during the Reconstruction era when newly freed African Americans were building institutions for their communities. In November of 1886, a group of former slaves and their children from the area – many of them members of the nearby Powelton New Hope Baptist Church – came together with a vision of establishing their own congregation. Under the leadership of community elders including Deacon Willie Peak, Deacon Abe Frazier, and Deacon Philic Jones, they founded Antioch Baptist Church on a plot of rural land just outside Crawfordville These pioneers had a clear goal: to expand their freedom and shape their lives as they saw fit, through faith, education, and community solidarity.

From the very start, the church’s founders demonstrated foresight and determination. The board of deacons acquired four acres of land from the Veazey family estate – two acres purchased and two donated – to establish both the church and a cemetery for the congregation. By securing land not only for a church building but also for a burial ground, the founders ensured their community would have a sacred place for both worship and remembrance. Oral histories and records indicate that the congregation initially met in a simple wooden structure or even outdoors until a more permanent sanctuary could be built.

Construction of the church’s sanctuary as we see it today took place in the late 19th century. According to historical surveys and local tradition, the present building was constructed around 1899 by local Black craftsmen. This means that the church members likely spent several years fundraising, gathering materials, and honing plans before they raised their own house of worship. The result was worth the wait. When it opened its doors (around 1899 or shortly thereafter), Antioch Baptist Church became one of the most impressive rural churches in Georgia. Built by the community for the community, the structure embodied pride and hope. Every timber in its frame and every nail in its beams told a story of self-sufficiency and faith. The congregation now had a permanent home – one where they could worship freely, educate their children, and celebrate life’s milestones, all under one roof.

A Unique Gothic Revival Design in Rural Georgia

One of the first things an urban explorer or visitor notices about Antioch Baptist Church is its unusual architecture. Unlike the simple designs common to many small country churches, Antioch boasts features that wouldn’t be out of place in a city cathedral. The front facade is symmetrically framed by twin Gothic Revival–style towers, which flank a broad central doorway. Each tower once held a belfry or steeple (though any bells have long gone silent), and together they give the church an almost imposing presence on the landscape. The church’s windows are tall and lancet-shaped, with pointed Gothic arches that filter light into the interior. According to preservationists, these decorative Gothic elements were handcrafted by the congregants and local builders without the aid of professional architects. It’s remarkable to think that a group of formerly enslaved people and their descendants, armed mostly with practical knowledge and creativity, designed such a distinctive building. They achieved an elegant interpretation of the Gothic Revival style – a design movement that had been popular in America from the mid-1800s into the early 20th century – and adapted it to their humble rural context.

The choice of the name “Antioch” for the church also carries significance. In the Bible, Antioch was an early center of Christianity where followers of Jesus were first called “Christians.” For many Baptist congregations, the name symbolizes a new beginning or a faithful community. While Antioch Baptist Church in Crawfordville didn’t have an official alternate name or nickname, some locals simply refer to it as “Old Antioch” or “Antioch Church” in conversation. It has also been mentioned in preservation circles alongside its cemetery, sometimes labeled Antioch Baptist Church and Cemetery. These names all point to the same beloved landmark. No matter what it’s called, the church stands out for its architecture and the aura of history that surrounds it.

Visitors often comment that they just don’t build them like this anymore. The craftsmanship is evident in features like the curved wooden ceiling of the vestibule, the hand-carved railings, and the sturdy heart-pine plank flooring that has survived over 120 years of use. The interior walls were originally natural wood, but in the mid-20th century they were covered with pastel-colored sheetrock paneling – perhaps an attempt to modernize the sanctuary’s look for a time. Peeling away sections of this later addition reveals the old timber underneath, which could potentially be restored to its 19th-century appearance.

For urban explorers in Georgia, the Antioch Church’s design is a dream to photograph. Its weathered white exterior contrasts beautifully with the greens and browns of the encroaching forest, and the twin towers create a striking silhouette against the sky. It’s no wonder Antioch has become a favorite subject for photographers traveling Georgia’s backroads. The church’s image has graced social media feeds, photography blogs, and even books about abandoned places. Yet no photograph can fully capture the feeling of standing in front of this building – a mix of admiration, curiosity, and a profound respect for the hands that built it.

Antioch Baptist Church Serving the Community: Worship, Education, and Gathering

During its active years, Antioch Baptist Church was more than just a Sunday sanctuary – it was the heart of a community. In an era when African Americans in the rural South faced segregation and limited opportunities, the church provided a safe space for spiritual uplift, education, and mutual support. Worship services were held regularly, likely on Sundays and for mid-week prayer meetings or Bible studies. Former members recall lively congregational singing resonating from the building. In fact, music was a cherished part of the worship tradition at Antioch; oral histories note that sometimes the congregation would even forego instruments and simply tap their feet in unison, creating a rhythmic foundation for their hymns and spiritual songs. This simple act of keeping time with their feet was a powerful expression of unity and faith, connecting worshippers in both body and spirit.

Beyond worship, the church played a crucial educational role. Shortly after the church’s founding and dedication, the congregation established a one-room schoolhouse on the property for their children. In those days (late 1800s through mid-1900s), public education for Black children in Georgia was woefully underfunded and segregated – if it was available at all. In Taliaferro County, Black students were not allowed to ride the county school buses well into the 1950s. Small church-run schools like the one at Antioch were therefore a godsend. They often provided the only access to formal education for rural African American youth prior to integration. In Antioch’s humble schoolhouse, children learned reading, writing, arithmetic, and scripture under the tutelage of community teachers. Imagine the scene decades ago: on weekdays, the joyful shouts of schoolchildren would ring out from a little wooden school building beside the church, the same place where on Sundays their families sang hymns and listened to sermons. This dual use of church property – for faith and schooling – underscores how vital Antioch was to local African Americans striving to improve their lives. The school remained in operation until the era of school integration and the advent of county “equalization schools” in the 1950s made it obsolete. (Indeed, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally paved the way for Black children in the South to attend better-funded public schools alongside whites, albeit with much resistance in places like Crawfordville.) Although the old one-room schoolhouse at Antioch was dismantled years ago and no longer stands, its legacy lives on in the stories of those who studied there and went on to educate others.

The church grounds also served as a venue for community gatherings and celebrations. Every year in August, Antioch Baptist Church hosted an annual revival and homecoming – a common tradition in Southern Black churches where members and descendants return “home” for special services, fellowship, and the spiritual recharge of revival meetings. These gatherings were joyous occasions with spirited preaching (often by guest ministers), plentiful gospel music, and communal meals on the grounds. According to the Historical Rural Churches of Georgia organization, Antioch’s descendants have continued this tradition even long after regular services ceased, holding an annual reunion at the church each August. Four generations of families have been known to travel from across Georgia and beyond to attend these homecomings, reconnecting with their roots and ensuring that the stories of Antioch are passed down to the young. It’s a touching sight to see: folding chairs and tables set up under the trees, elders sharing memories of the “old days” at Antioch, and children absorbing the history around them. This annual event demonstrates that while the church building may appear abandoned on most days, it is not forgotten – it remains a sacred place in the collective memory of its community.

Step inside the church’s dim interior today, and you can almost hear echoes of its active years. Physical remnants tell the story: The original wooden pews (over twenty of them) are still lined up neatly on the pine floor, their heavy, hand-hewn boards testifying to 19th-century workmanship. Faded hymnals and a Holy Bible rest on the pulpit, as if awaiting the preacher’s return. An upright piano stands silently in one corner; one can imagine the bright notes it once sounded during Sunday worship or choir practice. In a poignant display of trust and tradition, visitors have noted that an offering plate with money sits on the altar table, alongside hand-written notes. It seems to function as a community fund for those in need – people leave a few dollars, and those going through hard times might take some, often leaving a note with their name and a promise to repay when they can. This beautiful custom, continuing even in the church’s semi-abandoned state, speaks volumes about the values of the congregation: mutual aid, honesty, and faith in each other. Remarkably, despite being largely unsecured, the church’s interior has suffered little vandalism. Urban explorers and local visitors alike have treated Antioch with respect. Instead of graffiti and broken glass (fates that sadly befall many abandoned buildings), one finds order and reverence. This is likely due in part to the ongoing care by descendants – they periodically clean up, perform minor repairs, and keep the surrounding grounds mowed – and also due to the unwritten code of honor among those who visit. It’s as if everyone recognizes that Antioch Baptist Church is a time capsule of Black history and rural heritage, deserving of protection.

Trials and Tribulations: Fires, Challenges, and Local Legends

Running a rural church through the decades has never been easy, and Antioch Baptist Church faced its share of hardships. Perhaps the most devastating incident recorded in its history was a fire in the early 1920s that damaged the building. According to church members and local lore, Antioch “fell victim to a fire in 1921”. The cause of the blaze was never documented in surviving records. It may have been an accidental fire – not uncommon in those days of wood stoves and kerosene lamps – or it could have been due to a lightning strike. Some have even speculated in hushed tones that it might have been a case of arson, as sadly many Black churches in the South were targets of racist attacks in the Jim Crow era. However, without evidence, the true cause remains a mystery. What is known is that the congregation was determined to not let this setback be the end of their church. By pooling their resources and labor, they rebuilt the damaged sanctuary and officially rededicated it in 1923. The rebuilt structure likely incorporated and repaired parts of the original 1899 framework, maintaining the same Gothic Revival appearance and character. In fact, standing in front of the church today, one would hardly guess that a fire ever swept through it a century ago – a testament to the quality of the reconstruction and the pride the congregation took in restoring their house of worship.

Aside from the fire, Antioch Baptist Church navigated the everyday challenges of sustaining a small congregation in a changing world. The Great Depression of the 1930s and World War II would have tested the community’s economic strength and resolve. Many families in the area were sharecroppers or farmers; when times were lean, church donations and maintenance likely suffered. Despite this, the church endured, sustained by faith and frugality. There are anecdotes that during difficult years, the women of the church held bake sales and quilting bees to raise pennies and dollars for church upkeep, while the men volunteered their carpentry and repair skills.

By the mid-20th century, profound societal changes were underway. The younger generation began to move to cities like Atlanta or Augusta for better opportunities, leading to out-migration and a declining rural population in Crawfordville and surrounding communities. This gradual exodus meant fewer members filling the pews as the years went on. Yet, for a long time, a core group of devoted congregants kept Antioch’s doors open. They continued weekly services, albeit with smaller numbers, into the late 20th century. One key figure was Deacon George L. Turner, whose family had deep ties to the church (his father had been a deacon before him). For many years, Deacon Turner acted as a spiritual leader and caretaker, ensuring that worship persisted even when ordained ministers were scarce.

One might wonder if any scandals ever took place at this quiet country church. Unlike some big city congregations that have weathered public controversies, Antioch’s history appears largely free of scandal in the traditional sense. No salacious tales of misappropriated funds or infamous preachers dominate its story. However, there was indeed a period of turmoil in the mid-1960s that touched Antioch’s community, though it was part of a larger fight for justice rather than an internal church scandal. This was the time of the Civil Rights Movement, and tiny Crawfordville, Georgia was not isolated from the currents of change sweeping the nation.

The Civil Rights Era: Antioch Baptist Church’s Role in the Struggle

By the 1960s, Antioch Baptist Church had already been serving the African American community for over 70 years. As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum across the South, Black churches proved to be critical hubs for organization and activism – and Antioch was no exception. In fact, Antioch Baptist Church and its grounds became a local headquarters for civil rights meetings and voter registration efforts during this era. Oral histories and reports indicate that activists and community leaders would gather at the church to plan strategies to secure voting rights and equal treatment for Black citizens of Taliaferro County. The church’s relative seclusion (being off the main roads) provided a degree of safety and privacy for these planning sessions. It’s inspiring to think that within those wooden walls, by the glow of kerosene lanterns or dim electric lights, ordinary people plotted extraordinary changes – discussing how to challenge Jim Crow laws, how to register Black voters in the face of intimidation, and how to ensure their children could get the education they deserved.

One particular issue that catalyzed local action was the continued segregation of schools and school transportation in the county. As mentioned earlier, even after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, Taliaferro County had been slow to integrate, and Black students were still not allowed on school buses that took white children to the “good” schools. In 1965, this came to a head. There was a well-documented incident in nearby Crawfordville where African American students protested by blocking the paths of school buses carrying white students. They did so after being denied passage on those buses, effectively saying, “If we can’t ride, nobody rides.” This bold protest made the news – TV network archives from 1965 contain footage of the tense standoff and the resulting arrests of demonstrators. It was within this context of local strife that Antioch Baptist Church provided moral and logistical support. Activists held prayer vigils at the church and strategized there on how to press the county for change. The church also hosted voter registration drives, knowing that political power for Black citizens would be key to dismantling segregation. In those drives, local leaders (sometimes joined by organizers from larger cities or by members of the SCLC and NAACP) would train volunteers, distribute voter education materials, and even arrange transportation for people to go to the courthouse to register to vote.

There were risks to this activism. Taliaferro County was small in population but had a long shadow of plantation history; not all white residents welcomed the changes. Churches involved in civil rights were sometimes targeted – there are oral accounts suggesting that armed white men drove by Antioch on more than one occasion during 1965 to intimidate those inside. Some say shots were fired into the air as a warning. Others recall cross burnings near Black churches in the region (though none are definitively documented at Antioch’s location). If these frightening events occurred, the congregation of Antioch met them with courage. The church had, after all, been born from the resilience of former slaves – standing up to injustice was in its DNA.

This chapter of Antioch’s history underscores its historical significance beyond just architecture. In May 2024, recognition of that significance came in a big way: the National Park Service announced that Friends of Antioch, Inc. (a group formed to preserve the church) would receive a federal grant of $750,000 to help restore Antioch Baptist Church and its cemetery. In the grant announcement, it was noted that the church “was the site of voter registration drives and planning meetings for civil rights activists.” In other words, Antioch’s role in the African American Civil Rights Movement is now acknowledged as part of the national heritage, deserving preservation. This funding will assist with urgently needed repairs and stabilize the building so that future generations can physically step into the space where local heroes once stood up for equality. For urban explorers visiting today, knowing this context adds a layer of reverence: this isn’t just a photogenic old church – it’s a monument to the struggle and victories of the Civil Rights era in rural Georgia.

Decline and Abandonment: Why the Antioch Baptist Church Became Inactive

After surviving wars, the Great Depression, a fire, and the upheavals of the 1960s, Antioch Baptist Church remained a spiritual home for its congregation into the late 20th century. However, by the 1980s and early 1990s, several factors converged that led to the church’s effective abandonment (cessation of regular services). The primary reason was the decline in membership and leadership. As the older generation passed away and many younger folks had moved to cities, the congregation dwindled to only a handful of regular attendees. It became increasingly difficult to gather a quorum for weekly services, let alone afford a full-time pastor or maintain the aging building. Longtime deacon George Turner did his best to keep the church going, even leading prayers or inviting guest preachers occasionally. But when Deacon Turner passed away in February of 1992, it marked the end of an era. With his death, Antioch Baptist Church ceased holding regular services on Sundays. There simply was no one left to organize them consistently, and the few remaining members either joined other churches in nearby towns or continued their worship at home.

Another factor in the church’s closure was the condition of the building. By the early 1990s, the architecture was showing serious wear. The roof had developed significant leaks, causing water damage to the wooden structure. The foundation piers were eroding in places, and the floor had begun to sag in the front vestibule. The small bathrooms (added probably mid-century as a lean-to in the back) had deteriorated so much that they were eventually closed off entirely. Without a congregation to finance repairs, these issues compounded. While descendants did what they could on volunteer days – patching a hole here, replacing a broken window there – it wasn’t enough for a comprehensive fix. There was a real fear that if left unchecked, the church might literally collapse. A local historical survey around 2000 noted that the building was “in danger of being lost to neglect.” For this reason, preservation groups began to take interest. In 2020, The Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation listed Antioch Baptist Church on its “Places in Peril” – a list of the most endangered historic sites in the state – to raise awareness of its plight. They highlighted that while the church was still “much admired and photographed,” its lack of regular use had led to increasing neglect, and the building’s fate would depend on broader community support.

It’s worth noting that the term “abandoned” can be a bit misleading in Antioch’s case. Yes, it is an abandoned church in the sense of no active congregation or weekly services, but it has not been entirely left to ruin. As we’ve seen, devoted family members and historical enthusiasts have continued to care for it at a basic level and use it for special occasions. A more accurate description might be “semi-abandoned” or “preserved in a state of arrested decay.” Still, walking through its doors, one certainly feels the loneliness of a place that once rang with life and now sits mostly quiet. The air carries a faint scent of mildew and old wood. Bird nests occupy the eaves of the ceiling. A few scattered bulletins from decades past might still lie in the corners of pew racks, announcing church events that are long over. It is a place where time paused in 1992, and nature and history now intermingle.

As for any scandals or lore tied to its abandonment, none are widely recorded. There was no dramatic split in the congregation, no embezzlement, no infamous tragedy that caused the church to close. It was, in the end, the slow march of time and changing demographics that rendered Antioch inactive. Some locals do swap ghost stories and superstitions about the old church – common fare for any abandoned building with a cemetery next door. A few have claimed to hear phantom footsteps or distant singing when no one is there, or to see a flicker of light in the windows at night (perhaps the spirits of former members keeping eternal watch). Such tales, while intriguing, are more a product of imaginative minds on dark nights than any documented paranormal activity. The real “spirit” that haunts Antioch Baptist Church is the palpable sense of history and reverence one feels inside it.

The Cemetery: Stories Etched in Stone (and Unmarked Graves)

No exploration of Antioch Baptist Church would be complete without a visit to its adjacent cemetery. Just a few steps from the church’s front door lies hallowed ground where generations of the community have been laid to rest. Wandering among the aged tombstones, an urban explorer can glean as much history as from the church itself. Here, stately oaks and pines cast dappled shadows over modest marble headstones and simple fieldstone markers. Many inscriptions are now weathered and lichen-covered, but they tell of lives spanning the late 19th through 20th centuries. The earliest documented grave dates back to 1898, belonging to Reverend William H. Darden. Rev. Darden was born into slavery in 1856, gained his freedom as a young man, and became one of the early members (and by some accounts a minister) of Antioch Baptist. His resting place beneath a large pine tree at the front of the cemetery is a poignant link to the church’s founding generation.

As you explore further, you’ll notice the cemetery is not laid out in neat rows like a city graveyard. Burials appear in clusters, likely family plots, and some areas seem strangely empty. Those “empty” spots often aren’t empty at all – they mark unmarked graves known to the community. In many historically African American cemeteries, especially those tied to churches of modest means, not every grave received a permanent headstone. Wood markers rotted away over time, and some graves were simply left with no marker at all due to families’ financial constraints. Antioch’s cemetery is no exception. While about 30 to 75 graves have headstones or other records (sources vary on the count), it’s known that a roughly equal number of graves are unmarked. Deacon George Turner, in one of his final acts of stewardship, went through the cemetery in the 1970s and identified as many unmarked burial sites as he could, compiling a list of over 70 names or identities associated with them. Thanks to his efforts, even those without headstones are not forgotten in church records. Walking the grounds, you might see depressions in the soil or arrangements of rocks and fieldstones – telltale signs of those who slumber beneath.

Each grave has a story. There are veterans of foreign wars buried here, their service remembered with small American flags on certain holidays. There are matriarchs and patriarchs of local families, some living into their 90s. One can find the grave of Dock Peek (or Peak), born in 1852, who would have been a child during the Civil War and lived through Reconstruction to die in 1925 – likely a relative of Deacon Willie Peak who co-founded the church. The surnames on the stones – Darden, Peek, Frazier, Turner, and others – often match those of the founders and early members listed in church history. It’s moving to realize that the very people who built and nurtured Antioch Baptist are resting just outside its doors. The cemetery, with its mix of marked and unmarked graves, stands as a testament to the community’s continuity and the socio-economic realities of their times (as noted by HRCGA, headstones were “just beyond the reach” of many early 20th-century farm families).

Urban explorers visiting Antioch often find the cemetery profoundly affecting. It reminds us that abandoned places were once full of life – here lies proof of all the lives that were intertwined with this church. If you visit, take a moment to pay respects: tread lightly, perhaps brush off a bit of moss to read a name on a stone, and consider the hardships and triumphs those individuals experienced. Antioch’s graveyard is quiet, but it speaks volumes about African American resilience, faith, and community over more than a century.

Legacy and Preservation Efforts: Saving a Piece of History

Today, Antioch Baptist Church stands at a crossroads between decay and preservation. On one hand, time and the elements have not been kind to the old structure – each passing season of rain and humidity threatens to further erode its wood and stone. On the other hand, a passionate group of people are determined to save this piece of Georgia history. The formation of Friends of Antioch, Inc. in recent years has been a beacon of hope. Comprising descendants of the church’s founders and supporters of historic preservation, this group has worked to raise awareness and funds to restore the building. Their efforts, combined with recognition from state and national preservation entities, have begun to bear fruit. The 2024 National Park Service grant, as mentioned earlier, will provide a significant boost. Plans are underway to stabilize the foundation, replace or repair the leaking roof, and fix the damaged walls and windows. The goal is not to modernize Antioch, but rather to restore it to its former glory – essentially turning back the clock on deterioration so that the church looks as it did in its heyday, while making it safe for visitors.

The Historic Rural Churches of Georgia (HRCGA) organization has also played a role by documenting Antioch’s story, photographing it, and even creating a virtual 360-degree tour that allows people worldwide to “walk through” the sanctuary online. Such documentation is crucial; it ensures that even if disaster struck (be it a collapse or another fire), the knowledge and images of Antioch would survive. HRCGA has expressed that Antioch is “a very spiritual place that is difficult to describe… a photogenic profile… [that] can still be saved but time is running out.”. They emphasize that with enough community support and financial backing, Antioch’s structure can be successfully restored – the bones of the building are still strong, the timbers largely sound, and the building remains surprisingly plumb and square despite its age. The restoration, if completed, could allow the church to be used again for occasional services, reunions, educational tours, or as a small community events space. More importantly, it would stand as a permanent landmark honoring the people who built it and the history that unfolded there.

For now, any urban explorer venturing to Antioch should keep a few things in mind. Firstly, respect the site. While it might be an “abandoned church” in popular terms, it is private property cared for by a group of people. Treat it as you would a museum – leave no trash, do not remove anything, and be gentle if you step inside (the floors, though mostly sturdy, have soft spots). Remember that it’s not just a cool photo spot; it’s also akin to a memorial. Secondly, safety: as with any old structure, be cautious of where you walk. If you choose to explore the balcony or the area near the front towers, note that some wood might be weak. And watch out for critters – birds, bats, or the occasional snake might have taken up residence in the quieter corners.

Those considerations aside, visiting Antioch is absolutely worth it for the urbex enthusiast or history lover. The atmosphere is one of serene abandonment. On a sunny day, you might hear the chirp of birds blending with the distant sound of wind through the trees, as you stand where congregants once sang. On a misty evening, the place takes on an otherworldly beauty, the twin towers peering through the fog like sentinels of the past. It’s easy to let your imagination run at Antioch: perhaps you picture a wedding party gathered on the steps in the 1940s, or children walking to school with lunch pails in hand, or civil rights leaders huddled in discussion by the pulpit. The ghosts of history are strong here – not in a macabre way, but in a deeply meaningful way.

An URBEX Adventure Through History

Exploring the abandoned Antioch Baptist Church is a journey through layers of time. It’s the kind of adventure that exemplifies why urban exploring in Georgia can be so rewarding – you stumble upon places that are not only visually intriguing but also richly educational. Antioch offers a narrative that spans from the Reconstruction era of the 1880s through the civil rights era of the 1960s, right up to preservation efforts in the 2020s. Each peeling plank and each tombstone has something to say about the people who lived, worshipped, learned, fought, and died in and around this building.

In summary, Antioch Baptist Church in Crawfordville, GA was built in 1899 (organized in 1886) by freed slaves and served its community for roughly a century. It was a beacon of faith, a school for Black children during segregation, a gathering place for civil rights activism, and a anchor for families through generations. By 1992, due to population decline and the loss of its last active deacon, the church stopped holding regular services and entered a period of dormancy. Now often referred to as an “abandoned church”, it has nonetheless remained a site of annual reunions and the focus of restoration initiatives, rather than fading completely away. There were no notorious scandals to mar its legacy, but it did endure a destructive fire in 1921 (rebuilt by 1923) and the general hardships of the 20th century. The real story of Antioch is one of resilience and community spirit.

For those planning a visit, the church is located off a rural highway between Crawfordville and the tiny community of Powelton (from which its founding members originally came). There is no official address or visitor center – you simply find a small clearing and the proud old structure standing as it has for generations. The site is typically open (the door often literally ajar), but always ensure you have permission if possible, or at least introduce yourself to any locals you see and explain your interest. Often, they are happy to share a bit of history or show you around; they take pride in the church and appreciate sincere interest.

In closing, the abandoned Antioch Baptist Church is truly a hidden gem for urban explorers in Georgia. It combines the thrill of exploring an off-the-beaten-path location with the depth of learning about a significant chapter of Georgia’s African American history. Whether you’re drawn by the architectural allure of its Gothic towers, the quiet mystery of its sanctuary, or the profound stories carved in its cemetery, a journey to Antioch is bound to leave an impression. As you step back out into the sunlight, leaving the cool shadows of the church behind, you might just feel that you’ve walked alongside the spirits of the past – and become a small part of Antioch’s ongoing story yourself.

Antioch Baptist Church stands as a monument to those who refused to let their light be extinguished. Its future now hangs in the balance, but with continued support, this historic abandoned church could one day be fully restored, perhaps echoing with song again. Until then, it remains a place of reflection and adventure – a must-visit destination for anyone passionate about URBEX and the rich tapestry of stories found in abandoned places in Georgia.

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in the Charlton Memorial Hospital, the Haven House of Ocala in Florida, or the Abandoned House in Fort Pierce, Florida.

A 360-degree panoramic image capturing the exterior of the Antioch Baptist Church in Crawfordville, Georgia. Photo by the Abandoned in 360 Team

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Equipment used to capture the 360-degree panoramic images:

- Canon DSLR camera

- Canon 8-15mm fisheye

- Manfrotto tripod

- Custom rotating tripod head

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.