Old Craggy State Prison: Asheville’s Abandoned Penitentiary with a Haunting History

Step inside the history of Old Craggy State State Prison in Asheville, North Carolina—a stark concrete relic that still looms over the French Broad River corridor. Its weathered walls, guard towers, and overgrown yards hint at decades of discipline, routine, and restless stories waiting to be decoded by curious eyes.

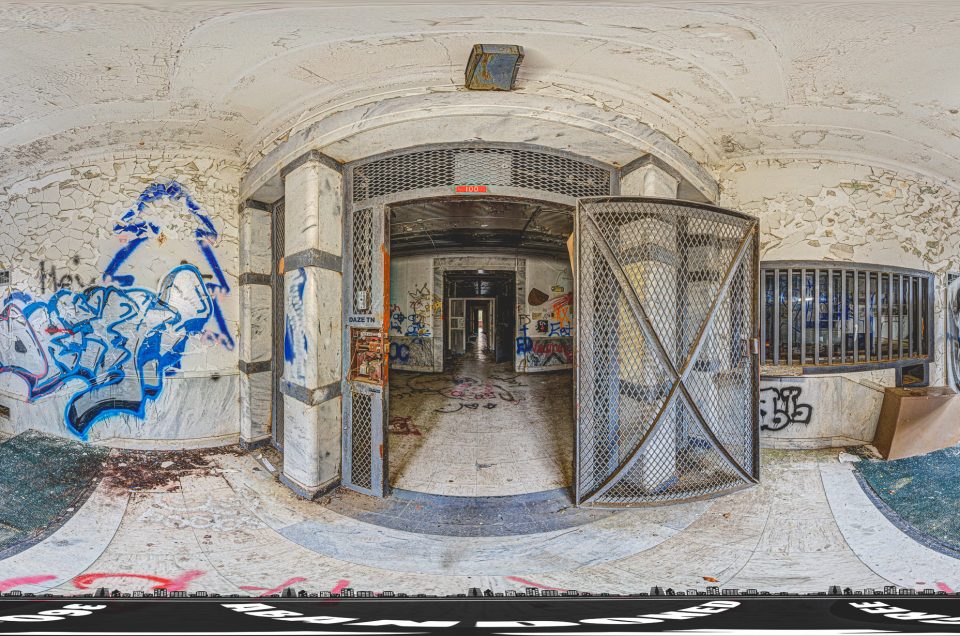

Use the aerial 360-degree panoramic virtual tour below to survey the entire complex from above. From this vantage point, urban explorers can trace perimeter lines, study rooflines and courtyards, and appreciate how nature is steadily reclaiming the grounds of Old Craggy State Prison—a compelling chapter in North Carolina’s industrial-era carceral past.

Click here to view it in fullscreen.

Old Craggy Prison in Asheville, North Carolina is an abandoned correctional facility steeped in nearly a century of history and legend. Erected in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains, this hulking penitentiary once housed hundreds of inmates and earned a fearsome reputation within the state’s prison system. Today, its empty cellblocks and decaying walls draw the curiosity of urban explorers (URBEX enthusiasts) fascinated by abandoned places in North Carolina. Built in 1924, Old Craggy Prison was a medium-security state prison that operated for over six decades. It saw countless prisoners, daring escape attempts, and even a full-blown riot within its confines. Eventually dubbed the “hell hole” of North Carolina’s prisons due to its harsh conditions, the facility was shut down in the late 1980s and left to crumble. In this blog post, we’ll delve into the history of Old Craggy Prison – from its construction and active years to the reasons for its abandonment – and explore the lore that surrounds this forbidding site. If you’re interested in urban exploring in North Carolina, read on to discover why Old Craggy Prison has become a legendary destination (albeit an off-limits one) for URBEX adventurers.

Origins of Old Craggy Prison – A 1924 Mountain Lockup

Old Craggy Prison’s story begins in the early 1920s. Dedicated in May 1924 by the Buncombe County commissioners, the prison was constructed on a 20-acre tract in the Asheville suburb of Woodfin. At the time of its opening, it was designed as a medium-security state prison with a capacity of around 500 inmates. The facility took its name from the nearby Craggy Bridge and the rugged terrain – an isolated location thought ideal for keeping prisoners securely away from the public.

In its original design, Old Craggy Prison was a formidable three-story structure. It featured seven open-air dormitory-style cell blocks and a row of solitary confinement cells tucked away in the basement. Notably, the prison lacked central heating or air-conditioning. This meant sweltering summers and frigid mountain winters inside Craggy’s concrete walls, conditions that made life miserable for inmates and guards alike. Despite these challenges (or perhaps because of them), the prison quickly filled with convicts from across Western North Carolina. Most of these early inmates were men serving time for a range of offenses, from minor felonies to more serious crimes, all under the watch of state authorities.

Old Craggy opened during a transformative era for North Carolina’s penal system. In 1931 – just a few years after the prison’s debut – the state passed the Conner Bill, which moved control of many county prisons to state authority. Craggy was one of 51 county-run facilities absorbed by the state under this reform. The 1930s also saw North Carolina embark on a massive push to improve its roads, and inmates became an integral part of that effort. Old Craggy Prison was one of 61 prisons either renovated or purpose-built in the late 1930s to house prisoners who worked on road construction crews. In other words, part of Craggy’s mission was to supply labor for building and improving mountain roads – a common practice at the time, when chain gangs and prison road crews were used to develop infrastructure. This focus on labor would shape daily life at Craggy for decades to come.

Life Inside Craggy – Work Gangs, Hard Labor and Daily Routine

During its operating years, the Old Craggy Prison was very much a working prison, with inmates routinely put to labor both inside and outside the facility. Day-to-day life for prisoners revolved around a strict regimen of work assignments, maintenance duties, and coping with the facility’s spartan conditions. Most of the inmates at Craggy were serving sentences for lesser felonies – crimes like theft, assault, arson, or embezzlement – rather than high-profile violent crimes. However, that doesn’t mean it was a gentle place. A number of inmates with heinous offenses such as rape or murder also served time there, so a mix of prisoner types occupied the dormitories. The environment could be tense and dangerous despite being officially “medium-security.”

Labor was a centerpiece of Craggy’s operations. From its early years through the mid-20th century, many inmates were assigned to outdoor work details – particularly road crews. These prisoners were sent to build and maintain public roads in the surrounding region. They filled potholes, painted highway lines, cleared brush, and even did rock quarrying in nearby areas like Weaverville. When roadwork was available, teams of convicts would spend long days toiling with picks, shovels, and other equipment under the supervision of armed guards. On days when the roads didn’t need immediate attention, inmates might be put to picking up roadside trash with minimal supervision – a testament to how routine these work gangs became. This use of inmate labor was part of a broader “prison road gang” system in North Carolina during the 1930s and beyond, where convicts effectively helped build the state’s infrastructure.

Inside the prison walls, other inmates handled support tasks. Craggy had a laundry facility on the grounds, and prisoners often worked there washing clothes and linens. In fact, laundry work was a daily assignment for many – they would wash as many as 50 loads of laundry, including their own striped prison uniforms and even the uniforms of correctional officers. It might seem ironic, but the inmates were responsible for keeping the guards’ shirts clean too. This on-site laundry would become significant later on (it’s one of the few parts of the property still in use today). Beyond the laundry, prisoners engaged in kitchen duties, maintenance, farming the small prison garden, or other menial jobs to keep the institution running. Every task was done under the strict regimen set by prison officials.

Life inside Old Craggy Prison was tough and primitive by modern standards. As noted, there was no climate control; inmates sweltered in summer and shivered in winter. From its inception in the 1920s up until around the 1950s, prisoners were issued the classic black-and-white striped uniforms, a practice eventually phased out mid-century. Overcrowding and minimal resources meant sanitation and comfort were perpetual issues. The dormitory-style cell blocks offered little privacy or respite. Violence among inmates was a constant risk – for example, the communal shower rooms were notorious as sites of beatings and assaults when guards weren’t looking. For those who broke prison rules or posed problems, the punishment was solitary confinement in the dark basement cells. Surviving accounts suggest that Craggy’s solitary cells were truly hellish: tiny, bare concrete rooms where troublesome inmates languished in isolation as a form of control.

Despite these hardships, some inmates tried to make the best of their sentences. The prison allowed a small incentive for labor: inmates who worked on the road gangs or in other jobs earned a token wage of 15 cents per day, paid out upon their release. By today’s standards that’s almost nothing, but at the time it gave prisoners a meager nest egg to start over with – and more importantly, the work itself taught them skills and discipline. Many convicts volunteered for tough work assignments specifically to learn a trade (such as laundry operations or road maintenance) they could use once free. In a sense, Old Craggy did offer some prisoners a chance at rehabilitation through work experience, even if conditions were harsh. However, those same conditions – hard labor, overcrowding, extreme temperatures, and the ever-present threat of violence – gave Craggy a dark reputation among inmates and officers alike.

Escapes, Riots and Notorious Incidents

Over the decades that Old Craggy State Prison was active, it witnessed numerous escape attempts, uprisings, and headline-making incidents that only added to its infamous aura. The combination of determined prisoners and the facility’s aging security infrastructure made escapes a recurring theme in Craggy’s history. In fact, Craggy became the first state prison in North Carolina to install an electronic intrusion system along its perimeter fence – essentially an alarm system to alert guards of escape attempts – precisely because breakouts were so frequent. Despite such measures, desperate inmates continued to test the prison’s limits.

One of the earliest and most brazen escapes occurred in February 1945, near the end of World War II. On a cold winter night, fourteen prisoners managed to break out of Craggy by sawing through the bars of a window and dropping about 15 feet to the ground outside. Under cover of darkness, the escapees climbed the fence and fled into the wooded hills behind the prison. The sheer number of men involved – 14 inmates in one go – made this escape especially notable. Local authorities responded swiftly: prison guards, Buncombe County sheriff’s deputies, state highway patrol officers, and bloodhounds were all deployed to track down the fugitives. Over the following days, a manhunt unfolded through the rugged terrain surrounding Asheville. In the end, most of the men were recaptured, but the 1945 escape attempt cemented Craggy’s reputation as a place from which prisoners were willing to risk everything to get free.

Craggy saw more than its share of such incidents. Escapes spiked again in the 1960s, by which time the facility was aging and perhaps easier to slip out of. In June 1964, a particularly chaotic series of breakouts made headlines. One afternoon, six inmates on a road work crew in Avery County overpowered a guard – viciously beating him over the head with a bush axe – and fled into the mountains. Amazingly, on that very same day, six other prisoners back at the Craggy compound climbed the fence and escaped from the yard, apparently taking advantage of minimal supervision. By nightfall, twelve convicts were on the loose in one day, prompting a huge search. By the next day, authorities had managed to round up a few, but nine men were still at large. In a surprising twist, two of the escapees actually turned themselves in: they showed up at a local Woodfin resident’s home at 11 PM and asked him to call the police to come get them, likely because they feared the intensive manhunt closing in. Others remained on the run longer. Among the fugitives was a 25-year-old serving a life term for first-degree murder, and another man serving 11 years for armed robbery – underscoring that even some very dangerous criminals were held at Craggy despite its “medium-security” designation. The prison’s director at the time, George Randall, blamed the spate of escapes on negligence and security shortcomings, noting that in one case the inmates literally pulled up a loose wire mesh door in the laundry building and crawled out under it to make their escape. Incidents like the 1964 breakout highlighted how outdated and vulnerable the facility had become.

Perhaps the most notorious event in Old Craggy Prison’s history was the riot of September 1975. Tensions inside the prison had been simmering, and one day a small band of inmates erupted into violence. The disturbance began with a stabbing, and then chaos spread through a dormitory. Prisoners started smashing windows and lit a fire that ultimately gutted one of the dorm buildings. As flames and smoke filled the wing, inmates piled mattresses onto the blaze to fuel it, and others ran amok breaking whatever they could. The riot was brief but destructive. By the time guards restored order, eight inmates were injured – most from smoke inhalation, one from a stab wound, and another who cut his hand on broken glass. The burned dormitory was left a blackened shell, with damage estimated in the thousands of dollars. Prison officials were puzzled by the outbreak of violence; they noted it seemed to come without warning or obvious racial or gang motivations. The 1975 riot underscored just how volatile Craggy had become in its later years. It also exposed the difficulties guards faced in controlling a facility that was overcrowded, understaffed, and literally falling apart around them.

That same week in 1975, amidst the post-riot chaos, an inmate pulled off yet another daring escape in a Hollywood-worthy fashion. A prisoner named Donald Ray Henderson had been taken off-site to Raleigh (Central Prison) for what was supposed to be a medical procedure – he claimed to have swallowed a razor blade, which showed up on x-rays. While being transported in a prison van, Henderson had secretly fashioned a makeshift firearm known as a “zip gun.” Seizing his chance during the drive, he put his homemade gun to the head of a guard, forced the vehicle to pull over on Interstate 40, and fled into the night. Henderson was no amateur at escaping; he had stolen a bus and kidnapped its driver earlier that month, and was due to face a grand jury for that prior escape attempt. His freedom was short-lived – two days later he was recaptured by deputies in Henry County – but his story became another of Craggy’s almost legendary incidents. Tales like Henderson’s added to the lore of Old Craggy Prison as a place of near-constant unrest and drama.

Not all of Craggy’s notorious moments were so grim; one even bordered on dark comedy. In 1952, an inmate named Grover C. Pressley briefly made the news for the novel legal defense he mounted after an escape attempt. Acting as his own attorney, Pressley stood before a Buncombe County judge and posed what he called the “Dog-Rabbit Plea.” He asked the courtroom: “If a dog catches a rabbit he is chasing, can it be said the rabbit escaped?” Pressley likened himself to the rabbit, arguing that since bloodhounds and officers were hot on his trail from the moment he fled a work gang, he was caught so fast it was as if he never truly escaped at all. The judge and jury were not persuaded by this clever semantics – Pressley was found guilty of escape and had three months tacked onto his sentence. (His two accomplices, who did not bother with inventive pleas, also received short extensions to their sentences.) The “Dog-Rabbit” episode became a bit of prison lore, illustrating the lengths to which Craggy inmates would go in hopes of a little relief.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, newspaper headlines repeatedly painted Old Craggy State Prison as one of the roughest facilities in the state. All the escapes, riots, and colorful stories earned it infamy. In fact, it was often referred to as “the hell hole” of North Carolina’s prison system – a nickname born from its appalling conditions and violent incidents. Former officers and inmates later confirmed that by the latter 20th century, Craggy was in a class of its own for decrepitude and danger. The prison’s security was porous, its amenities were nil, and it flunked virtually every test for modern correctional standards. This mounting notoriety set the stage for what needed to happen next: either drastic improvements or permanent closure.

Decline and Closure of “The Hell Hole”

By the early 1960s – after nearly 40 years of operation – officials openly acknowledged that Old Craggy State Prison was obsolete and inadequate. Reports from that era note that the prison had no space for recreation, education, or rehabilitation programs, and that its security features were far below acceptable standards. In 1964, the North Carolina Prison Department floated plans to replace Craggy with a new facility, provided the state legislature could appropriate funds. At the time, Prison Director George Randall estimated it would cost over $230,000 just to renovate and “fireproof” the old prison enough to be safe. Rather than pour money into the aging structure, the recommendation was to build a modern prison from scratch in the Asheville area. However, bureaucratic delays and budget constraints stalled any immediate action. It would ultimately take another two decades before Craggy was finally closed and replaced.

The turning point came in the 1980s. This was an era of reckoning for many antiquated prisons across the United States, especially in the South. Inmates began filing lawsuits over inhumane living conditions, and federal courts started taking these complaints seriously. North Carolina was no exception. At Old Craggy Prison, a pivotal lawsuit in 1986 helped seal the facility’s fate. Two inmates, with the help of attorney Lou Lesesne, sued the state over the atrocious conditions inside Craggy. They argued (rightly) that the prison was unsafe, unsanitary, and severely overcrowded – in essence, unfit for humans. Testimony and evidence painted a grim picture: the building was infested with rats and roaches, ventilation was poor, plumbing and electrical systems were failing, and the structure was “environmentally unsound” from decades of neglect. It was hard to keep clean, and virtually impossible to properly heat or cool. By this time the roof was leaking and parts of the prison were literally crumbling. In 1986, conditions at Craggy were so bad that Lesesne described the prison as “in a class by itself” – worse than any other in the state’s system. The inmates won their case in court, validating the claims that Old Craggy violated basic standards.

North Carolina’s leaders knew they had to act. The state legislature put together an emergency plan to upgrade its prisons. In 1987, the General Assembly approved nearly $30 million for prison improvements statewide, including about $8.4–8.5 million specifically to replace Old Craggy Prison with a new facility. Construction of the new prison began soon after. The new site was only about three miles up the road from the old one – far enough to start fresh, but still in the same general area of Buncombe County along the French Broad River. In May 1989, the new Craggy Correctional Center opened and the last inmates were transferred out of the old prison. After roughly 65 years of operation (1924–1989), the doors of Old Craggy Prison were shut for good. The “hell hole” that had once been packed with men and echoed with the sounds of daily prison life fell eerily silent.

It’s worth noting that Old Craggy State Prison was essentially abandoned as soon as the new facility came online. Unlike some institutions that get repurposed, Craggy was simply mothballed. State officials had no immediate use for a dilapidated 1920s prison building, especially one laden with hazardous materials like asbestos and lead paint. There were also no funds allocated to demolish it at the time. So the building was padlocked, fenced off, and left to the elements – a fate not uncommon for large public structures that outlive their usefulness. The new prison (often referred to as Craggy Correctional Institution today) took over the role of housing Asheville’s medium-security inmates in a modern, 312-bed complex. Meanwhile, Old Craggy began its next chapter as an abandoned relic – one that would soon attract its own kind of attention from the outside world.

Abandoned and Off-Limits: Old Craggy State Prison Today

In the decades since its closure, Old Craggy State Prison has stood empty and deteriorating, a hulking abandoned North Carolina landmark frozen in time. Driving along Riverside Drive in Woodfin today, you can spot the facility’s looming brick facade behind layers of chain-link fencing and warning signs. The once-bustling prison is now a boarded-up, crumbling shell of its former self. Its windows are shattered or covered with plywood, the roof is caving in, and nature has begun to reclaim parts of the structure. Weeds and vines creep up the sides of cellblock walls. The whole scene is often described as something out of a horror film – and indeed, at a glance, Old Craggy Prison looks every bit the classic haunted prison of one’s imagination.

Importantly, the site remains property of the state Department of Public Safety and is strictly off-limits to the public. The perimeter fence is meant to keep out trespassers and curious explorers, and for good reason. Inside, the building is dangerously unstable and contaminated with hazardous materials like asbestos and lead-based paint. Any disturbance to the structure could send toxic dust into the air. In fact, state officials have cited the high cost of asbestos abatement as a primary reason the prison hasn’t been demolished yet. As of a 2015 estimate, it would cost around $400,000 to safely tear down Old Craggy, and each year that passes likely pushes that price tag higher. So far, it’s been a low priority in the state budget, meaning the building is left to “sit and slowly crumble,” as one local legislator put it.

For now, the state has no active plans to redevelop or remove Old Craggy State Prison. It hasn’t even been declared surplus property – it’s just a dormant asset in the state’s portfolio. There was talk in recent years among local officials and preservationists about possibly restoring the old prison or designating it a historical landmark, given its unique history. Some envision it as a museum or tourist attraction someday (similar to how prisons like Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia have become museums). The site also sits on potentially valuable real estate near the French Broad River, leading others to imagine commercial redevelopment if the buildings were removed. However, none of those ideas have gained real traction. The combination of environmental hazards, structural decay, and funding hurdles means Old Craggy continues to languish in a kind of limbo. As one state engineer remarked, each passing year pushes the structure “past the point of economic recovery” – every harsh winter and wet summer further erodes what’s left.

Interestingly, one part of Old Craggy’s legacy is still alive – the laundry. Remember the on-site laundry building where inmates once labored over endless loads of uniforms? That laundry facility is still operational to this day, run by North Carolina Correction Enterprises (the prison labor industry program). In a separate support building behind the main prison, modern minimum-security inmates are bused in each week to wash laundry for the state’s prison system. According to reports, about 50–60 inmates and several supervisors handle dozens of loads of inmate uniforms daily on industrial machines. Steam can sometimes be seen rising from the back of the property – an eerie sight of life amidst an otherwise silent ruin. Other than this laundry operation, however, the old prison grounds serve no active purpose. The laundry workers are likely the only people who go behind the fences regularly, and they only access the separate laundry building (they wouldn’t step foot inside the derelict cell blocks for safety reasons).

For everyone else, Old Craggy State Prison stands as a ghost of North Carolina’s past – literally and figuratively. Locals driving by can’t help but rubberneck at the ominous structure. It has become an eyesore for some, a historic icon for others. Urban explorers and curiosity-seekers are irresistibly drawn to it, even though getting inside is illegal and dangerous. In 2016, it was reported that at least 17 people attempted unauthorized visits to the prison, causing minor damage in the process. The state has since tightened security, and the property is closely monitored to deter trespassers. “No Trespassing” signs, padlocked gates, and barbed wire send a clear message that the only residents of Old Craggy now are the pigeons and perhaps a stray raccoon or two. Yet despite the barriers, this abandoned prison in North Carolina continues to captivate the imagination of those who pass by.

URBEX Adventures: Urban Exploring Old Craggy Prison in North Carolina

Given its dramatic appearance and eerie atmosphere, it’s no surprise that Old Craggy State Prison has become a legend in the URBEX community. URBEX – short for urban exploration – is all about seeking out abandoned man-made structures, and this sprawling, decayed penitentiary is about as classic an URBEX site as it gets. In fact, many enthusiasts of urban exploring in North Carolina rank Old Craggy State Prison high on their list of must-see (or at least must-photograph) abandoned places. From the outside, you can glimpse guard towers looming over the yard and rows of prison windows now dark and empty – truly a haunting scene for any explorer with a camera.

However, would-be explorers should note that accessing Old Craggy State Prison is strictly forbidden. The site is patrolled and fenced, and trespassing there can result in arrest. As tempting as it is to sneak in and get a closer look at the peeling paint and rusting cell bars, the safety hazards are very real. The floors inside may be unstable, parts of the ceiling have collapsed, and as mentioned, toxic substances like asbestos could harm anyone who disturbs them. Urban explorers often operate in a legal gray area, but in this case the state has made it clear that the property is off-limits for any unauthorized entry. So, the golden rule of URBEX – “take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints” – unfortunately cannot even be applied here, because you can’t (legally) go in to take those pictures! Most have to admire Old Craggy from a distance, peering through the fence or perhaps flying a drone overhead for a look at the courtyard within. Indeed, some illicit drone footage has circulated online, showing glimpses of the decaying interior – rows of empty bunks, graffiti from past trespassers, and nature creeping into cellblocks. These images only deepen the fascination, giving a taste of what it’s like inside the abandoned prison that urban explorers wish they could fully explore.

For those interested in the haunted history aspect of Old Craggy, the site has plenty of lore to offer. Over the years, locals have come to regard Old Craggy Prison as one of the most haunted places in Asheville. It certainly looks the part of a haunted house: a nearly 100-year-old ruin steeped in pain and suffering. But how haunted is it really? Stories are hard to verify, yet a few chilling tales persist. Some neighbors and trespassers have claimed to hear strange sounds – the echo of footsteps in empty halls, disembodied voices, or the clang of cell doors when no one is there. Others swear they’ve seen shadowy figures moving past broken windows at dusk. One particularly intriguing legend is that of “the woman in white.” According to this tale, a spectral woman dressed in white is sometimes seen walking down the hill from the nearby Church of the Redeemer, only to vanish near the prison’s rear fence. Who she is supposed to be – perhaps a former prison nurse, a warden’s wife, or something else entirely – remains a mystery. This ghostly anecdote adds a layer of gothic folklore to the prison’s already dark reputation.

It’s important to note that no official records point to specific hauntings or supernatural events at Craggy. In fact, research hasn’t uncovered any documented inmate deaths on site that would obviously spawn ghosts (most prisoners who died in custody would have been transferred to hospitals or the state’s central prison). Nonetheless, the creepy vibe of the place is undeniable, and sometimes a creepy vibe is all it takes for ghost stories to flourish. Asheville’s reputation as a quirky, haunted mountain city only fuels the speculation. Tour companies even include drive-by views of Old Craggy on their ghost tours, regaling tourists with the legends as they pass the dark silhouette of the prison at night. Whether or not one believes in ghosts, it’s easy to see why urban legends cling to Old Craggy Prison. The site embodies that perfect storm of history and mystery: violent true events combined with decades of abandonment and decay.

For urban explorers who love photography, Old Craggy is a dream subject – from a lawful distance, of course. The juxtaposition of stark architecture and encroaching decay makes for powerful images. Some explorers have gotten permission for limited access (for example, journalists or historians occasionally get escorted onto the grounds but not inside the building). Photographer Leland Kent of “Abandoned Southeast” was one such person; he documented the prison’s interior in 2019, capturing haunting photos of empty corridors and rusted cell doors. These photographs show paint peeling off the walls in sheets and vines snaking in through cracked windows – a visual testament to time’s relentless toll. Such imagery only furthers the prison’s allure among the URBEX crowd.

In summary, Old Craggy Prison holds a near-mythical status in North Carolina’s urban exploring circles. It’s an “endgame” location – the kind explorers talk about in hushed, excited tones, even if few will ever set foot inside. While the site must be respected as private property and a dangerous environment, the spirit of adventure lives on in those who dream of one day hearing their own footstep echo in Craggy’s empty mess hall or shining a flashlight down its dark cell rows. Until that day (if it ever comes), we are left with secondhand accounts, photographs through broken windows, and our own imaginations to envision the stories these ruins could tell.

Legacy and Outlook for Old Craggy Prison

As Old Craggy Prison approaches its 100th anniversary, it stands at a crossroads of history, memory, and neglect. On one hand, the prison is a valuable historical artifact – one of the few remaining early 20th-century penitentiaries in the region, bearing witness to how far correctional standards have come. Its very nickname, “the hell hole,” and the fact it was shut down by court order highlights a critical chapter in the history of prison reform in North Carolina. The site holds stories of prisoner road gangs that built our highways, of depression-era chain gangs, of wartime escapes and 1970s riots, all the way to legal battles in the 1980s that improved human rights behind bars. In this sense, preserving at least part of Old Craggy – or commemorating it – could serve as a powerful educational tool. Some have advocated for adaptive reuse of the complex (if it could be made safe), imagining it as a museum of crime and punishment, or a monument to those who suffered and persevered there. This would mirror projects in other states where old prisons have been opened for tours, allowing the public to walk through cellblocks and understand the harsh realities of past prison life.

On the other hand, the practical challenges are enormous. The cost of environmental remediation and structural stabilization is very high, and funding has been elusive. The state representative for the area has warned that every year the problem gets costlier and the structure gets more dangerous, arguing that doing nothing is not a viable long-term plan. If the prison is neither torn down nor restored, it will eventually collapse under its own weight, possibly creating an even more hazardous ruin. In recent years, there have been inklings of interest from unexpected quarters – for instance, Hollywood scouts have eyed Old Craggy Prison as a potential film set. One can certainly imagine a movie or TV show using this authentic 1920s prison as a dramatic backdrop. Thus far, safety concerns have prevented such use, but a controlled film project might, in theory, provide funds or impetus to stabilize parts of the site.

For now, the official stance (as of the latest updates) is to maintain the status quo: keep the site secure, operate the laundry, and wait until a clear decision is made. As one spokesperson for the Department of Public Safety put it, Old Craggy is closed but “retained for DPS use” – basically on standby, even though that use is minimal. It has not been sold off or handed to the state’s surplus property office, which means any future action will likely come from within the state government itself. Whether that action will be demolition, preservation, or something in between is still unknown.

What is certain is that Old Craggy State Prison continues to captivate all who learn about it. For local residents of Asheville, it’s a familiar landmark – a hulking reminder of a bygone era visible from the road, stirring questions and stories. For history buffs and urban explorers, it’s an object of intrigue and adventure, representing the intersection of history, decay, and the human imagination. And for former prisoners and staff who are still alive, it’s likely a source of complex memories – some might look at the decaying building and feel relief that it’s closed, while others might remember it as the place where they turned their lives around or formed unbreakable bonds under hardship.

In the grand timeline, Old Craggy Prison’s active life was relatively short, but its legacy endures. It stands as a stark symbol of how dramatically penal philosophy has changed – from an era of chain gangs and “hell hole” prisons to today’s focus (however imperfect) on rehabilitation and humane conditions. And it also symbolizes the fate of many abandoned places in North Carolina and across the country: when the world moves on, these imposing structures remain, caught between collapse and preservation.

Conclusion

Old Craggy State Prison is more than just an abandoned building on the outskirts of Asheville – it’s a silent repository of North Carolina’s penal history and a beacon for adventurous souls fascinated by the past. Built in 1924 at a time when hard labor was the cornerstone of incarceration, Craggy witnessed decade after decade of change, struggle, and human drama. Within its walls, prisoners toiled on road gangs for a few cents a day, plotted daring escapes, endured riots and violence, and ultimately helped spark reforms by challenging their grim living conditions. The prison’s operating run stretched for roughly 65 years, long enough to imprint itself on the collective memory as a place of punishment and infamy – hence the “hell hole” moniker it earned. Its abandonment in 1989 was not just the end of a prison, but the end of an era.

Today, the site’s decaying presence continues to evoke awe and unease. Urban explorers and history enthusiasts are drawn to Old Craggy Prison like moths to a flame, even if only to gaze from behind the fence at its weathered guard towers and cellblock windows. Stories of ghosts and strange sights add a layer of folklore, ensuring that the prison’s mystique lives on even in emptiness. As the debate carries on about what to do with this crumbling giant – whether to tear it down, save it, or simply let it be – one thing is clear: Old Craggy Prison will not be forgotten. In the annals of Asheville and North Carolina history, it remains a powerful, haunting symbol of both the darkness of the past and the undying curiosity of those who seek to understand it.

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in learning about the The Whitener House in Florida, the New York City Farm Colony in New York, or the Contrabando Movie Set in Texas.

An aerial 360-degree panoramic image of the exterior of the Old Craggy State Prison in Asheville, North Carolina.

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Equipment used to capture the 360-degree panoramic images:

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.