Abandoned Olympic Village of Berlin: A Historic URBEX Adventure in Germany

Take a look at The Olympic Village of Berlin in Germany—an abandoned site that still carries the echoes of a massive international event and the decades of history that followed. Today, it stands as a striking example of how places built for celebration can slip into silence, leaving behind architecture, atmosphere, and stories written into every weathered surface.

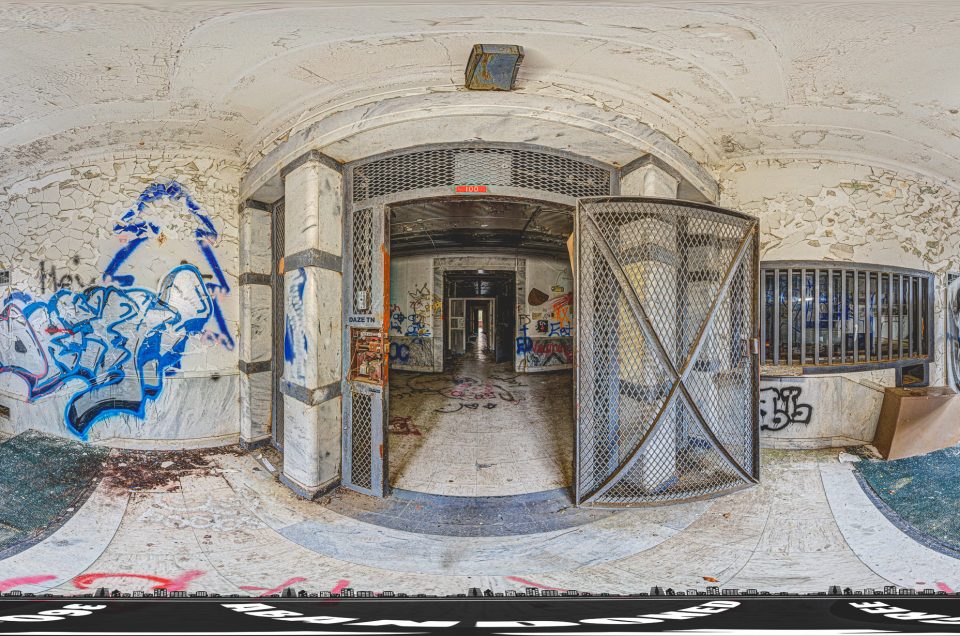

Explore The Olympic Village of Berlin through the panoramic images on Google Maps Street View below, where you can scan the grounds from multiple angles and spot details you might miss in a quick visit. For urban explorers, it’s a rare chance to study a famous location up close—at your own pace—while appreciating the scale, layout, and haunting beauty of a place time forgot.

Photo by: Di Wan

Photo by: Di Wan

Photo by: Di Wan

Photo by: Michael Groeneveld

Photo by: Di Wan

Just beyond Berlin’s bustling city limits, hidden in the quiet fields of Wustermark, the Olympic Village of Berlin stands frozen in time. This once grand complex – built for the 1936 Summer Olympics – now lies abandoned, its crumbling structures and overgrown paths whispering stories of a bygone era. For those passionate about urban exploring in Germany, this site is a dream come true. It’s one of the most intriguing abandoned places in Germany, offering a URBEX adventure that blends rich history with the thrill of discovery.

Walking through the deserted dormitories and dining halls, you can almost hear the echoes of Olympic athletes who roamed here during the village’s brief glory days. Ivy clings to brick walls where flags of dozens of nations once fluttered, and the silence is broken only by the crunch of gravel underfoot or the rustle of wind through the trees. It’s hard to imagine that this ghostly village was once a state-of-the-art residential complex buzzing with energy and camaraderie. Yet the Olympic Village of Berlin – nicknamed the “Village of Peace” in its time – has transformed into an eerie playground for urban explorers, offering a haunting journey through both history and decay.

In this blog post, we’ll travel back to 1936 to uncover how and why this Olympic Village was constructed, what life was like for the athletes who stayed here, and how a place of youthful celebration became a relic of the past. From its conception under Nazi propaganda to its abandonment after decades of military use, we’ll explore the key events that shaped this unique location. We’ll also delve into the scandals and secrets that surround it – including propaganda ploys, personal tragedies, and Cold War mysteries. Finally, for the modern adventurer, we’ll look at what remains today and why this decaying Olympic Village has become a must-see destination for urban explorers seeking adventure in Germany.

Building the “Village of Peace” (1934–1936)

The story of the Olympic Village begins in the early 1930s, when Berlin was chosen to host the 1936 Summer Olympics. The International Olympic Committee awarded Berlin the games in 1931 – before the Nazi Party rose to power – intending to welcome Germany back into the international sporting community after World War I. However, by the time construction of the Olympic facilities began in 1934, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis were firmly in control and eager to use the Olympics as a stage for their ideology.

Hitler personally oversaw plans for the Olympic Village in Elstal, a rural area of Wustermark about 14 kilometers west of Berlin’s Olympiastadion (Olympic Stadium). The village was envisioned as more than just athlete housing; it was a showcase for German efficiency, hospitality, and the regime’s grandiose vision. Chief architect Werner March – who also designed Berlin’s monumental Olympic Stadium – drew up plans for a permanent village that would impress visitors and athletes alike. Built on a 550,000 square-meter (135-acre) tract of land owned by the army, the complex went up between 1934 and 1936. Each structure was built with a dual purpose in mind: to serve Olympic athletes during the games, then convert into military barracks and training facilities once the sporting events concluded.

Despite military oversight behind the scenes, the Olympic Village was designed to resemble a peaceful country town. Hitler dubbed it the “Village of Peace,” and its layout featured dozens of cozy one- and two-story dormitory bungalows spread among tree-lined lanes and gardens. In total, 136 residential buildings (often called “huts”) were constructed to accommodate the competitors. To add to the idyllic feel, each dorm building was named after a different German city or town – giving the international guests a charming introduction to German geography as they strolled through the lanes.

No expense was spared in making the village state-of-the-art for its time. The facilities included everything an athlete could need: dormitories with modern plumbing and heating, a large dining hall complex known as the “Speisehaus der Nationen” (House of Nations), a fully equipped gymnasium, an indoor swimming pool, multiple sports training fields, and even a theater/assembly hall in the central administration building. The House of Nations dining hall featured around 40 separate dining rooms – one for each delegation or group of nations – so athletes could enjoy meals tailored to their home cuisine. Smaller nations without their own kitchens shared with others (for example, the lone athlete from Haiti dined alongside the Brazilian team). A man-made lake with swans and other waterfowl (brought from the Berlin Zoo) added to the picturesque atmosphere, and even a lakeside wooden sauna cabin was built for relaxation.

By the spring of 1936, construction was complete and the Olympic Village was ready to be shown off. In a bid to impress the public and quell international worries about Germany’s intentions, the Nazi authorities opened the village to visitors for several weeks before the games. From May 1 to June 15, 1936, crowds of curious people toured the facilities – an estimated hundreds of thousands of visitors came to see this “Olympic utopia” in person. The open-house was a propaganda success. The village appeared as a tranquil, welcoming haven of international friendship, neatly concealing the militaristic purpose that lurked in its design.

Glory Days: Life in the Olympic Village during Summer 1936

The Berlin Olympics officially opened on August 1, 1936, and with them, the Olympic Village sprang to life. For about two weeks, this rural corner of Wustermark became a cosmopolitan mini-city housing athletes, coaches, and staff from around the world. Approximately 4,000 athletes from over 50 countries lived in the village, making it one of the largest athlete residences the Olympic Games had seen up to that point.

Daily life in the Olympic Village of Berlin was a blend of intense training and cultural exchange, all under the watchful eye of Nazi officials. Each morning, athletes woke in their comfortable two-person rooms, ate breakfast in their designated national dining hall, and headed out to train for their events. The complex had a sports hall and fitness center where teams could practice indoors, as well as outdoor tracks and playing fields for athletics. Swimmers and divers trained in the village’s own aquatic center, an indoor pool facility that was bright and modern for its era. Legendary filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl roamed the village during these training sessions, filming scenes for her documentary “Olympia.” She captured athletes sprinting on the track, boxing in the gym, and cooling off in the sauna by the lake – showcasing the athleticism and camaraderie of the competitors in a way that doubled as Nazi propaganda for physical prowess.

When not training or competing, athletes could unwind in the village’s recreational areas. The Hindenburg House (named after Germany’s late president Paul von Hindenburg) served as the administrative and social hub of the village. It housed a theater and even a television lounge where athletes could watch live broadcasts of the competitions – a novelty at the time, since the 1936 Games were the first Olympics ever televised. (Indeed, experimental live TV broadcasts from the village and stadium were pioneered during these games, an impressive technological feat for 1936.) Outside Hindenburg House, a grand stone relief of marching soldiers by artist Walter von Ruckteschell stood at the entrance, subtly blending militaristic imagery into an otherwise friendly environment.

Meals were another memorable aspect of village life. In just over two weeks of occupancy, the thousands of athletes consumed prodigious quantities of food – according to records, they ate approximately 100 cows, 91 pigs, and more than 650 lambs, and drank around 8,000 pounds of coffee! The dining hall bustled with activity at mealtimes as teams gathered in their allotted dining rooms decorated with national flags. It was a chance for athletes from different sports and countries to mingle under one roof. Many later recalled the Olympic Village as a highlight of the Berlin Games – a place where camaraderie and sportsmanship flourished, at least for a short time.

Despite the mostly positive experience for athletes, there were underlying tensions and strict controls. Nazi guards were ever-present, and propaganda messages were woven subtly into the village environment. Olympic rings and swastika banners hung side by side on buildings. The regime took care to temporarily remove anti-Jewish slogans and tone down its oppressive policies during the Games, to avoid alarming international guests. Hitler’s government was intent on showing the world a sanitized, peaceful image of Germany.

One famous example of reality clashing with propaganda was the story of American track star Jesse Owens. Owens – an African American sprinter who won four gold medals in Berlin – became a celebrity resident of the Olympic Village. His victories undercut the Nazi narrative of Aryan racial superiority. According to later reports, the Gestapo monitored all athlete communications; they even intercepted phone calls and mail. In one instance, a fan’s letter urging Owens to protest by rejecting his medal was confiscated before Owens could see it. Inside the village, however, Owens was treated with respect and admiration by fellow athletes (German and international alike), defying Nazi stereotypes. His presence and success were quietly celebrated among competitors, even as Hitler famously avoided congratulating him publicly.

The Olympic Village had its share of personal drama too. Captain Wolfgang Fürstner, the village’s original German commandant, was removed from his post just before the Games due to his partial Jewish heritage. Another officer took over, and Fürstner – distraught at his treatment – tragically took his own life on the village grounds three days after the Olympics ended. Nazi officials covered up his August 1936 suicide by reporting it as a “car accident” to avoid scandal. Only later did the truth emerge: the very regime that hailed the Olympic Village as a symbol of peace had driven its commander to despair through bigotry.

By August 16, 1936, the Olympics drew to a close. The athletes departed, taking their memories of competition and camaraderie with them. The Olympic Village’s brief time in the global spotlight was over – it had operated as an athletes’ haven for just those few weeks. But the story of this place was far from finished. As the Olympic flame was extinguished, the German military was already poised to move in and repurpose the “Village of Peace” for a far different purpose.

From Olympians to Occupiers: Military Use and Wartime Secrets

True to the plan from the start, the Olympic Village barely had time to rest after the Games before it was transformed into a military installation. By December 1936 – only a few months after the last athletes left – the site was officially taken over by the German Army (Wehrmacht). It became the Infanterieschule Döberitz, an infantry training school and barracks. The cheerful House of Nations dining hall that once fed global athletes was soon converted into a hospital for German troops. The Hindenburg House, with its theater and lounges, was repurposed as a school and lecture hall for Wehrmacht officers. The dormitory huts became soldiers’ barracks. The very design features that made the village comfortable for Olympians – its spacious campus and numerous facilities – also made it an ideal ready-made base for the army.

World War II broke out in 1939, and over the next several years the former Olympic Village served the Nazi war effort. Young recruits drilled on the same fields where record-breaking runners had trained. Wounded soldiers were treated in the makeshift hospital on site. Any remaining veneer of Olympic idealism quickly vanished as Nazi Germany pursued its military ambitions. The village’s transformation from a symbol of international goodwill to a cog in the war machine was complete – and deeply ironic given its nickname.

In April 1945, as Nazi Germany collapsed, Soviet forces advancing toward Berlin captured the Olympic Village. The once-celebrated site fell under new occupation, this time by the Red Army. The Soviets took over not only the original Olympic buildings but also the adjacent German military camp areas. They promptly adapted the complex to their own needs in the early Cold War period. For nearly 50 years, the Olympic Village remained behind the Iron Curtain, used as a Soviet military base. The occupiers constructed stark new additions: plain, rectangular apartment blocks (Plattenbauten) sprang up at the edge of the complex to house Soviet officers and their families. These boxy concrete buildings clashed with the quaint village-style architecture of 1936, but they provided the necessary accommodations.

There are even dark rumors about the Soviet era at the Olympic Village. It is said that the basement of the swimming pool building – once a place of leisure for athletes – was used as an interrogation and detention center by Soviet intelligence agencies (like SMERSH or the KGB) during the late 1940s and 1950s. Whether or not these specific stories are true, it’s clear the Soviets left their mark. They painted over Nazi murals with their own symbols and artwork; one notable mural of Lenin pointing forward was added in the theater hall, and a painting of Red Army soldiers raising the hammer-and-sickle flag was placed where a German military relief had been. The Olympic Village, meant to celebrate peaceful competition, had become a restricted military zone wrapped in secrecy.

For decades, few outside the armed forces got a glimpse of this place. Local Germans knew it simply as part of the large Soviet garrison at Döberitz. The global significance of the site was largely forgotten until the Cold War ended. Finally, in 1992, after the reunification of Germany and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the last Russian soldiers withdrew from the Olympic Village. After roughly 56 years of continuous military occupation (first by Germany, then by the USSR), the historic complex was left empty and silent once more. The athletes were long gone, the soldiers had departed, and the “Village of Peace” faced an uncertain future as a derelict remnant of history.

Decades of Neglect: Abandonment and Decay

When the military era ended, the Olympic Village entered a new phase: complete abandonment. In the 1990s, Germany suddenly found itself responsible for many disused military sites left by the Cold War, and the Olympic Village was one of them. Initially, there was no clear plan (or funding) for the site’s reuse. So it sat in limbo – too historically important to demolish, yet costly to maintain. In the absence of caretakers, nature began reclaiming the village. Weeds and grasses cracked through the once-pristine sidewalks; vines crawled up the walls of dormitories; and rainwater seeped in through damaged roofs, accelerating the decay. Windows shattered or left ajar invited the elements inside. The elegant swimming hall dried out and gathered dust, its tiled pool basin empty and echoing. Paint peeled off the locker room walls in sheets, and rust corroded metal fixtures.

For a long time, the site remained largely unknown to the general public, hidden in plain sight outside Berlin. However, word slowly spread among history buffs and the urban exploring community that a fascinating abandoned site lay waiting in Wustermark. Intrepid explorers began venturing past the perimeter fence to glimpse this forgotten piece of 20th-century history. What they found was a time capsule of contrasts: an overgrown sign still bearing the Olympic rings here, a Soviet star graffitied on a wall there, a mix of 1930s architecture and 1970s concrete block apartments all succumbing to the elements. Photographers were particularly drawn to the village’s melancholic beauty – its long empty corridors and sunken courtyards where silence and memories lingered.

Unfortunately, the lack of oversight also led to vandalism and looting. Over the years, many original artifacts from 1936 that might have survived the war and Soviet period were stolen or destroyed. Souvenir hunters carried off anything from signage to fixtures, and vandals left graffiti tags on historic walls. By the early 2000s, few traces of the Olympic glory days remained beyond the shells of buildings themselves. It was clear that if nothing was done, the village would eventually crumble away entirely.

Recognizing the site’s historical importance, local authorities placed the original Olympic Village structures under monument protection. In the mid-2000s, a German bank’s foundation (DKB Stiftung) stepped in to stabilize and preserve key parts of the complex. Crews repaired some roofs to keep buildings watertight and cleared out dangerous debris. Special attention was given to the former dormitory building that had housed Jesse Owens – restoring one of its rooms to how it would have looked in 1936, complete with period furniture and decor. The foundation also began offering occasional guided tours, turning the village into a sort of open-air museum-in-progress where visitors could safely walk through history.

Meanwhile, developers and city planners eyed the large site as a candidate for redevelopment. By the 2010s, concrete plans emerged to integrate the Olympic Village into a modern housing project while preserving its core historical elements. As Berlin’s population expanded, the pressure for new residential areas pushed the project forward. Around 2018–2019, work began on converting the western portion of the village into a new neighborhood. Some of the crumbling dormitories were carefully gutted and rebuilt as apartments and townhouses (with their historic exteriors maintained). Even the grand dining hall was slated for conversion into a residential building, retaining its facade as a nod to the past. At the same time, the eastern half of the complex – including landmarks like the Hindenburg House, gymnasium, and pool – was set aside to become a permanent historical monument and exhibition area.

Secrets, Scandals, and Historical Significance

The Olympic Village of Berlin isn’t just an architectural curiosity – it’s a place where some extraordinary chapters of history overlap. From Nazi propaganda stunts to Cold War secrets, the village has been at the crossroads of significant events and controversies.

One major historical issue tied to the 1936 Olympics was how the Nazi regime used the games for propaganda while hiding its darker side. In the lead-up to the Olympics, German Jewish athletes and other minorities were largely barred from competition. Facing the threat of international boycott, Hitler’s government made superficial concessions – such as including the part-Jewish fencer Helene Mayer on the German team (she won a silver medal) – to keep up appearances of fairness. This token gesture didn’t reflect reality: soon after the Olympics, the Nazis intensified their persecution of Jews. The Olympic Village stands as a physical reminder of this hypocrisy: it was built to celebrate peace and brotherhood, even as the government behind it was preparing for war and oppression.

The story of Jesse Owens further highlights this contrast. Owens’ stunning victories were a rebuke to Nazi racial ideology. Hitler’s reputed snub of Owens (by not greeting him after his wins) became an enduring symbol of prejudice confronted by excellence. In the village, Owens and other non-white athletes experienced an unusual few weeks of equality and hero’s treatment, even as they knew that outside the gates, racism was the law of the land. Today, one of the most celebrated spots in the Olympic Village is the preserved room of Jesse Owens – a testament to how one man’s achievements punctured the myth of Aryan superiority.

The tragedy of Wolfgang Fürstner is another sobering piece of the village’s legacy. The fact that the Olympic Village’s own commander was driven to suicide by the very regime hosting the games was a scandal that the Nazis swept under the rug. It wasn’t widely known in 1936 (due to the cover-up), but later generations learned that even those who toed the line for Hitler could become victims of his racist policies. Fürstner’s fate adds a human face to the abstract concept of Nazi intolerance.

Fast-forward to the Cold War, and the Olympic Village gains a different type of historical significance. It was essentially a secret city during those decades – a place off-limits to ordinary citizens, repurposed for military training and perhaps espionage-related activities. While not widely publicized, the village’s use as a Soviet barracks for so long means that this site witnessed the full arc of East Germany’s existence from beginning to end. The lingering Soviet graffiti and infrastructure tell a tale of their own, about the spread of communism into the heart of Europe after World War II.

On a more positive note, the 1936 Olympic Village was also the site of some “firsts” that left a lasting mark on sports history. It was one of the first Olympic Villages that was purpose-built and meant to be a lasting fixture (earlier Olympics had more temporary athlete housing). The success of the Berlin village helped popularize the Olympic Village concept for future games. Moreover, the technological feats – like those pioneering live television broadcasts – showcased modern innovation and foreshadowed how important media and tech would become in sports.

All these layers make the Olympic Village of Berlin a uniquely significant place. Scandal and triumph, innovation and tragedy – they all coexist in the peeling paint and cracked concrete. This village is not just an abandoned cluster of buildings; it’s a silent witness to some of the 20th century’s most defining moments.

Urban Exploration Today: Visiting the Olympic Village

For today’s urban explorer, the abandoned Olympic Village of Berlin offers an adventure that is both historically enriching and tinged with the thrill of discovery. Few places in the world allow you to wander through an Olympic ghost town, and this one comes complete with echoes of both Nazi pageantry and Cold War intrigue. Exploring the site is like stepping into a time warp where multiple eras collide.

Officially, parts of the Olympic Village can be visited via guided tours arranged through the site’s managing foundation. These tours are the safest and most informative way to experience the village – you get context from experts and access to some buildings that have been stabilized for public entry. On a tour, you might walk through the restored athlete quarters, see Jesse Owens’ room, and stand inside the famous dining hall (now an empty shell) as a guide narrates its past. You’ll also likely visit the swimming pool building and other key sites, with safety precautions in place.

Of course, the allure of URBEX is often to explore on your own. It’s worth noting that while the Olympic Village is no longer completely off-limits, unsupervised access is technically trespassing and security patrols do monitor the area – especially around the portions under redevelopment. Nonetheless, many urban explorers have managed to sneak a peek over the years. If you venture here on your own, you must be extremely careful, both for your personal safety and to avoid legal trouble. The structures are old and some areas might be hazardous (with broken glass, unstable floors, or asbestos), and getting caught by security could end your adventure early.

That said, let’s imagine what you’ll find if you do get to wander the Olympic Village today. Some notable sights include:

-

Dining Hall (House of Nations): The once-bustling central dining facility stands as an imposing ruin with its neoclassical facade and tall columns. Inside, the 40 kitchens and dining rooms are long gone – now it’s an echoing, empty space where sunlight filters through broken sections of the roof. It’s easy to picture athletes from every corner of the world dining under this roof, even as you stand in silence among the remnants.

-

Athletes’ Dormitories: Dozens of low brick and stucco bungalows dot the grounds, many in advanced states of decay. Peering into these former living quarters, you’ll see small rooms that held a couple of beds each. Personal touches are gone, replaced by graffiti and dust. One of these buildings has been partially refurbished to display how it looked in 1936, but many others are open to the elements. It’s poignant to walk down the little “streets” between them, with faded name plaques (bearing names of German towns) sometimes still visible beside the doorways.

-

Swimming Pool & Gymnasium: The indoor sports complex, including the pool, is one of the eeriest areas. The pool lies empty and cracked, beneath a ceiling that has been partly repaired by conservationists to prevent collapse. You can almost hear the splash of swimmers and the cheers that once echoed off these walls. Adjacent to it, the gymnasium or sports hall has tall glassless windows that light up the dusty interior. Broken equipment and wall bars might still be strewn about. The atmosphere here is both serene and spooky – a temple of sport turned into a hall of ghosts.

-

Soviet Barracks: On the outskirts of the village, you’ll encounter the utilitarian concrete apartment blocks added by the Soviets. These buildings are stark and boxy, now just empty shells with peeling paint and collapsed staircases. Walking through these barracks, you shift into a different time period – Cold War rather than Olympic glamour. In some corridors you might spot remnants of Cyrillic writing or Soviet red star emblems. These structures drive home how the site’s purpose changed so completely over the years.

Exploring the Olympic Village is an exercise in imagination. As you move from one area to another, you effectively travel through time – from the hopeful pre-war era of 1936 to the tense mid-century military occupation. The contrast between the more ornate, village-like buildings and the later utilitarian ones tells a story all by itself.

If you plan to visit, remember to be respectful. This site is a protected historical monument and a war grave of sorts (given the history and even the tragedy of Fürstner). Take only photographs, and be mindful of your surroundings. Every piece of graffiti or broken glass has a backstory of people who might not have respected the site – try to leave no new marks behind.

For those unable to join a formal tour, even standing at the perimeter fence can be worthwhile. You’ll see the outline of the village and maybe catch glimpses of buildings between the trees. Some urban explorers come at dawn or dusk to capture the village in magical light – golden rays filtering through the ruins, or mist rising among the old houses. The feeling of solitude and reflection you get from this place is hard to describe.

Conclusion

The Abandoned Olympic Village of Berlin in Wustermark is more than just a collection of old buildings – it’s a stage upon which history played out in dramatic fashion. In its time, it hosted youthful dreams and international camaraderie. Later, it witnessed the march of armies and the weight of geopolitical tensions. Now, it stands quietly, inviting us to ponder the lessons and stories it holds.

For urban explorers, visiting this village is both exciting and enlightening. It’s not every day you get to walk through an Olympic venue that time forgot. Every faded mural or derelict dormitory here has something to say: about the glory and hubris of the Nazi era, about the grim realities of war and occupation, and about the inevitable decay that follows when places are left to history. The contrast between what it was and what it is now can give you chills. One moment you’re imagining the laughter of athletes in the sunshine; the next, you’re reminded of the soldiers who replaced them, and finally of your own footsteps crunching in the silence.

Efforts to preserve the Olympic Village ensure that its story will not be lost. As restoration and redevelopment continue, future generations may see this place in a new light – perhaps as a park, a museum, or even a neighborhood with an extraordinary past. But even as it changes, the spirit of the village as a symbol of a complex history will remain.

Whether you come for the historical significance or the adventurous thrill of urban exploring, the Olympic Village of Berlin leaves an indelible impression. It teaches us that even grand achievements can be fleeting, and that the remnants of the past can speak volumes if we stop to listen. So if you ever find yourself on Berlin’s outskirts with a few hours to spare and a taste for adventure, consider seeking out the old Olympic Village. Step carefully through its gate, take a deep breath of that cool, heavy air inside, and let the past and present blur around you. It’s a journey you won’t soon forget. Happy exploring!

If you liked this blog post, you might be interested in reading about the Liu Family Mansion in Taiwan, the Devinska Kobyla Missile Base in Slovakia, or the Sant Salvador de la Vedella in Spain.

A 360-degree panoramic image at the Olympic Village of Berlin. Photo by: Di Wan

Welcome to a world of exploration and intrigue at Abandoned in 360, where adventure awaits with our exclusive membership options. Dive into the mysteries of forgotten places with our Gold Membership, offering access to GPS coordinates to thousands of abandoned locations worldwide. For those seeking a deeper immersion, our Platinum Membership goes beyond the map, providing members with exclusive photos and captivating 3D virtual walkthroughs of these remarkable sites. Discover hidden histories and untold stories as we continually expand our map with new locations each month. Embark on your journey today and uncover the secrets of the past like never before. Join us and start exploring with Abandoned in 360.

Do you have 360-degree panoramic images captured in an abandoned location? Send your images to Abandonedin360@gmail.com. If you choose to go out and do some urban exploring in your town, here are some safety tips before you head out on your Urbex adventure. If you want to start shooting 360-degree panoramic images, you might want to look onto one-click 360-degree action cameras.

Click on a state below and explore the top abandoned places for urban exploring in that state.